The sense of housing crisis is nearly everywhere. Debates about housing policy are heating up, turning once arcane fields into the subject of fevered Facebook exchanges. Housing prices are shooting past their pre-recession highs and people across Los Angeles are feeling the squeeze like never before. Home ownership within a reasonable commute to job centers is out of the question for all but the upper echelons of society. Among young urban professionals, there’s a scramble to find “about to get hot” working-class neighborhoods in which to rent and buy. Rents in previously affordable neighborhoods are rising so fast that tens of thousands of people are being pushed into homelessness.

The loudest voices of the YIMBY (“Yes In My Back Yard”) movement are confident they have the solution. California’s coastal cities have a shortage of supply relative to demand because of selfish NIMBY (“Not In My Back Yard”) homeowners and their political enablers who’ve severely limited the construction of new housing over the last four decades. The story is simple — with clear villains and Econ 101 logic at work. To them, the solution is clear — we need to override local zoning with state legislation so millions of new housing units can be built across the state. California Senate Bill 827 intends to do just that. Spearheaded by Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco), and the Silicon Valley-backed California YIMBY. Wiener’s S.B. 35, passed last year, streamlines construction if cities aren’t on track to meet their housing production goals. S.B. 827 takes this much further, with a specific focus on areas near rail and bus lines. In its initial form, Wiener’s bill 1) prohibits density restrictions or parking requirements within a half-mile of a major transit station or a quarter-mile of a bus stop on a frequent bus line; and 2) sets the maximum-zoned height in these areas at 45, 55, or 85 feet depending on the nature of the street in these same areas.

In Wiener’s telling, the bill is about equity. He writes “The only way we will make housing more affordable and significantly reduce displacement is to build a lot more housing and to do so in urbanized areas accessible to public transportation.” More audaciously, he frames S.B. 827 as a measure that “tackles head on the ugly reality that mandated low-density zoning excludes poor people and—per the intent when low-density zoning was created 100 years ago—people of color.” Wiener cites Richard Rothstein’s much-lauded new book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, as support for his position.

This makes sense. We cannot reckon with this housing crisis without inquiring into our country’s metropolitan history. We need to ask and think about several important questions along these lines.

- Is the lack of residential construction primarily responsible for our current affordability, gentrification, and displacement crises?

- How and why did density restrictions come into being?

- What has been the role of political and institutional racism in carving up the metropolitan landscape and creating inequality?

- And how should these historical contexts shape the solutions we craft today?

* * *

Rothstein’s book is an important place to start. From the fevered reception it received, one might think it was the first work of scholarship on the “public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States.” But his work draws heavily from a large body of historical and sociological research on the topic. Rothstein acknowledges his great debt to classics like Thomas Sugrue’s Origins of the Urban Crisis and Arnold Hirsch’s Creating the Second Ghetto. Those works, in turn, owe greatly to scholars like the legendary W. E. B. Du Bois and to movement organizers like Dr. Martin Luther King who critiqued “internal colonialism.”

I remember reading Origins of the Urban Crisis in 2004 as an undergraduate and being shocked at how little I knew and how little exposure its detailed findings had received. As I wrote my senior thesis on the failures of “urban renewal” in Newark, NJ, via “slum clearance” of mixed neighborhoods, segregated public housing projects, highway construction, and other infrastructure decisions, the reality became vividly clear to me, as much as when I walked from the train station to the Newark Public Library as in the archives themselves.

When I entered a history doctoral program at USC, propelled by this knowledge and a sense of obligation to tell the story, I discovered dozens of books and articles from the field of urban studies chronicling the disinvestment from and destruction of urban neighborhoods populated heavily by people of color, especially African-Americans. And what I’ve learned along the way is that Wiener and his YIMBY allies are telling a much-abridged version of American’s metropolitan history.

The housing history of metropolitan America does include zoning with origins in racism, classism, and sexism. And it surely includes attempts by the privileged, especially single-family homeowners, to limit the “wrong” kind of people from living in their neighborhoods, through methods like restrictions on multi-family housing. But to operate on the pretense that racial discrimination is solely or primarily the result of government restrictions on land use is to ignore the fact that as a whole, all of mainstream white society, and especially investment capital, is complicit in the reality of segregation, economic inequality, and lack of housing opportunity.

This history has contributed to a segmented housing market such that increases in aggregate supply, will not necessarily produce lower costs for poor and working-class communities. The massive shortage of low-cost housing is not only the result of anti-density restrictions in affluent neighborhoods. It owes in great part to a legacy of wealth-suppression and outright exploitation, facilitated by private capital that has so often made its profit by moving the color line while relying on government subsidy.

This means that challenging the anti-density policies entrenched by privileged homeowners is only one piece of the puzzle. If we don’t tailor pro-density policies to explicitly counter a legacy of redlining of access to jobs and capital, and to preserve and create affordable housing, then the YIMBY agenda will perpetuate and not remedy the inequities that well-meaning YIMBYs intend to oppose.

Recent pieces concisely make the case for YIMBY introspection about their relationship to justice movements. This essay seeks to deepen the discussion by offering a big-picture, long-term context for the debates we’re having in 2018.

* * *

Urban history has taken an unusual trajectory in the United States. Unlike other countries where the political, financial, or cultural capitals stood at the center of the nation’s society, much of American identity was premised on a rejection of the “big city.” As important as Eastern seaboard ports were in the early 19th century or how vital Chicago was to the development of an industrial nation in the early 20th century, the dominant culture centered on the notion of a “self-made” (white) man striking out on his own. Equally important as the “frontier” farmer myth and reality to American identity were “urban boosters.” These boosters were civic leaders and land owners in innumerable towns and cities who attempted to create self-fulfilling prophecies which would attract more residents and more investment, thereby increasing their own wealth and power.

This occurred in the U.S. far more than other countries because of the extreme decentralization and fragmentation of government authority here. A growth-for-growth’s sake narrative pervaded urban discourse. The answer to any problem was more people and more capital. Of course, not all places could win the battle for growth. And the ones that did briefly reach the summit, like Chicago, were vulnerable to displacement, as people and capital pursued opportunity elsewhere.

The result was an urban capitalist economy undergirded by property speculation and frequently struck by alternating booms and busts. Investors getting into the market at its zenith lost out, of course, but no one stood to lose more than renters who suffered from rapidly escalating housing costs followed by economic collapse that eviscerated their incomes. Through the early 20th century, the sheer abundance of land and the paucity of land use regulation meant that housing costs were relatively low. But the unregulated market in cities — geared toward maximizing the profits of those narrow class of people who owned capital and held sway over government — led to horrific and unsanitary conditions. This was especially true in the “slums” chronicled in How The Other Half Lives by photographer Jacob Riis. It also did little to prevent racial segregation.

In the first half of the 20th century, there was very little question that the market had failed. There was widespread agreement across the political spectrum that a new level of coordination was needed, usually by the government, to re-assert control and restore order on behalf of the collective in the wake of laissez faire’s social wreckage. The real divide was over what kind of order ought to be restored, by what means, and for whose benefit. It was in this context that all of modern planning, zoning, and housing regulation initially developed.

Racism — or more accurately belief in the superiority of whiteness among those considered white — inflected much of this emerging field. Boosterish business and civic leaders infamously called for Los Angeles to be the “whitest spot on the map.” The phrase specifically referred to L.A.’s anti-labor, pro-capital business environment, but as Bill Deverell shows in Whitewashed Adobe, the racial overtones were not subtle — leading Angeleno Joseph P. Widney spoke for the elite consensus in proclaiming that "the Captains of Industry are the truest captains in the race war.” As a result of corporate, homeowner, real estate, and government redlining, places like Boyle Heights and Watts became diverse communities full of Jewish (not considered sufficiently white at the time), Japanese, Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and African-Americans. And it was those same places and the historic Eastside generally to which white-owned private capital and new zoning rules pushed polluting industries.

However, there was another aspect of the planning field. It comprised the smaller proportion of professionals who sought to use land use regulation and government investment for the exact opposite purpose — to alleviate suffering caused by lack of adequate, affordable housing. It started with settlement house pioneers like Jane Addams who pushed for regulations to ensure enough air and light circulated through packed tenement apartments. It expanded through the tradition “housers” like Catherine Bauer who sought to mitigate the failures of the boom-and-bust cycle of unchecked real estate speculation and profit-seeking capital. In the 1920s, a social democratic movement in cities like New York successfully created garden-style housing cooperatives to remove housing away from the pressures of the marketplace.

In the 1930s, municipalities and the federal government began working to replicate these developments with public funding. Whether in New York, Newark, or Los Angeles, these projects were initially a success — well-designed and well-funded.

As Gail Radford notes in Modern Housing for America, housers pushed an ambitious agenda of “non-commercial development of imaginatively designed compact neighborhoods with extensive parks and social services,” drawing inspiration from the successes of what was called “social housing” in Europe. Most audaciously, Rex Tugwell, a leader in President Roosevelt’s Administration sought regional level planning that would “provide an alternative to private speculative development, with the community retaining land ownership and political control over future expansion.”

This path was decidedly not the one our nation’s metropolitan areas followed.

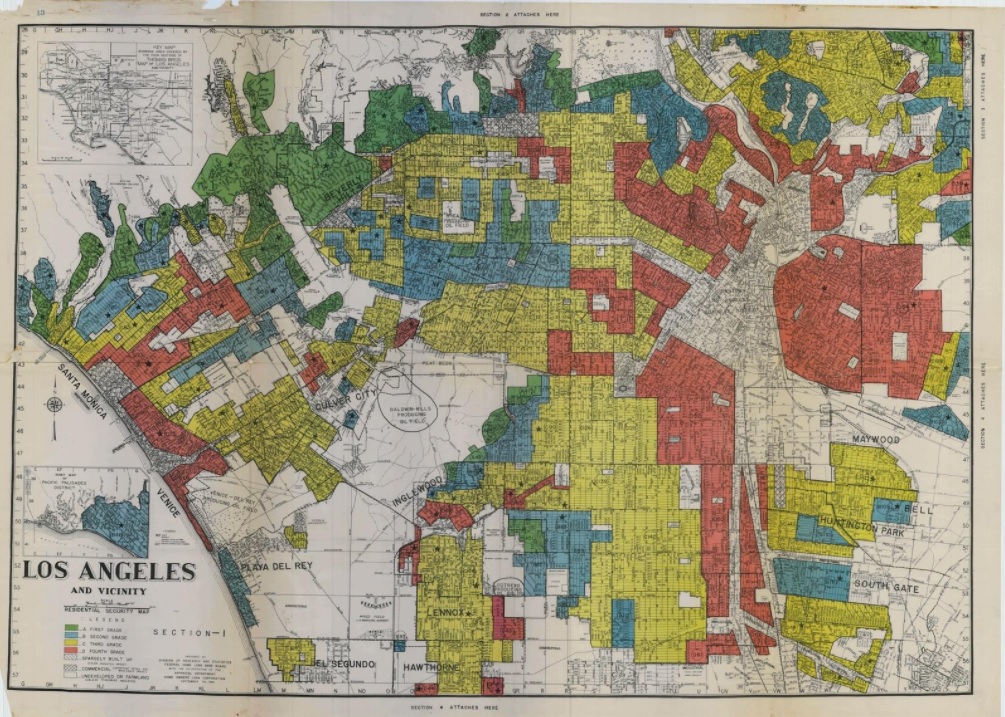

What occurred instead was a market-driven development that was both generously subsidized by the federal government and racially discriminatory. The trickle of federal funding for public housing in the 1930s was nothing compared to the subsidy provided by Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), which effectively subsidized the mortgages of millions of homeowners. The HOLC is the source of the infamous color-coded maps of cities, which determined which neighborhoods would be eligible for loans based on their racial mixture. Like many before him, Rothstein notes, the impact of these maps.

But recent scholarship demonstrates that it wasn’t solely planning that discriminated, but also private capital. These HOLC maps followed the patterns already set by banks. Federal support had the effect of entrenching practices already followed by the dominant white businesses and homeowners, while further subsidizing them. This would be the pattern that has dominated our housing history ever since.

World War II brought an end to the Depression but created a housing crisis of its own. People flooded into cities for new work opportunities, especially African-Americans who left behind the Jim Crow South only to be confronted with sub-par wages, exploitation by slumlords, and in many cases, vicious white violence aimed at preventing their entry into certain neighborhoods. Little new housing was built during the war and what was built, whether public or private, was almost never available to African-Americans. As veterans returned from the war and began to start families, the housing shortage reached a new depth of crisis.

The solution, at least in the aggregate, was a wave of single-family, mass-produced tract homes in suburbs like the San Fernando Valley, Southeast L.A. County’s Lakewood, and East Coast Levittowns.

Subsidized by the Federal Housing Authority, the suburban building boom helped to recreate the white middle-class after the Depression, giving even (white) blue-collar workers a plot of land and a decent building to call their own, a la the white frontier farmer of 19th century. Developers — and their investors — profited handsomely. Win-win? Hardly. Left behind in worsening conditions were the communities of color who had been systemically excluded from these subsidies AND from the new market construction. Capital flight combined with segregated suburbanization to leave inner-city neighborhoods to grow more overcrowded and more physically dilapidated.

Civic leaders — white, male, upper-class (the sons of those calling for L.A. to be the “whitest spot on the map”) — came to see these neighborhoods as “slums,” a blight on their city’s image. Rather than directly invest in the people who lived there, civic leadership sought to transform the physical space into something that would match their booster dreams. “Urban renewal,” just like suburbanization, involved pouring millions in public funding toward privately-developed projects whose investors made a tidy profit while new inhabitants enjoyed “modern” space.

In Los Angeles, Chavez Ravine was cleared of ramshackle housing, with the honest intention of constructing 10,000 units of public housing, before a conservative mayor came to office and ended up selling the land to the Brooklyn Dodgers. At the same time, the Bunker Hill Redevelopment Project tore down many square blocks of old homes to make way for new corporate office towers and “public” plazas, a story repeated in cities and towns across the country. Federally funded freeways sliced through the neighborhoods left behind by redlining, with more than five highways going through Boyle Heights alone, causing massive displacement, cutting Hollenbeck Park in two, and leading to an epidemic of air pollution. Construction companies profited. Newly suburbanized middle-class workers were able to glide seamlessly to their downtown jobs. The mass transit of the day – Yellow Cars around downtown and Red Cars connecting neighborhoods across the entire metropolitan region – was decommissioned.

This did not happen without resistance.

Progressive Angelenos on the left-wing of the Democratic Party like Reuben Borough warned against abandoning the mixed public spaces—the parks, squares, and railcars in favor of a retreat into segregated neighborhoods, connected only by private automobiles. This group, following in the tradition of “housers,” wanted equitable transit-oriented development. In the 1930s and 1940s, they fought for improved equipment and services for public transportation to reduce overcrowding and wait times. Seeing the region’s explosive growth, they backed the creation of a countywide master plan for transportation under public ownership and operation. Financed by long-term, self-liquidating bonds, it would offer lower fares, more lines to newly developing communities and expanded cross-town service. They worked to create more health facilities in places like Watts and the growing San Fernando Valley. They advocated to create parks, playgrounds and community recreation centers, especially in low-income areas. They proposed the expansion of municipal beach facilities, including parking, bathhouses, cafeterias, as well as public auditoriums across the city.

This visionary group lost and lost badly. They lost to the privateers — both to 1) private capital and real estate interests which fought mercilessly against attempts to satisfy the supply of housing, transportation, and public places through government planning and 2) a white homeowner class which got their backyards and freeways supplied by private businesses and heavily subsidized by the government. There was a lot of money to be made from the color line, as N.B.D. Connolly has shown in his work on metropolitan Miami. There was lots of wealth to be accumulated from moving around poor people, especially poor people of color.

Repressive policing was endemic in the work of getting and keeping these groups in their place. It was the combination of policing, economic deprivation, and metropolitan segregation, which fueled and then ignited the urban uprisings of the 1960s, Watts prominent among them. In this post-Watts context in 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King spoke frankly of internal colonialism. “In the slum, the Negro is forced to pay more for less, and the general economy of the slum is constantly drained without being replenished,” he exclaimed in a speech at the Chicago Freedom Festival. “The slum is little more than a domestic colony which leaves its inhabitants dominated politically, exploited economically, segregated and humiliated at every turn.”

At the instigation of homeowners and other wealthy property interests, the city’s voters approved a ballot initiative in 1969 that limited the number of people who could live on a plot of land and capped the number of stories a building could have as an effort to contain the “wrong kind” of people, i.e. those from redlined inner-city neighborhoods from encroaching. By cutting density in half, it prevented the even dispersal of jobs across the city. In 1986, this tradition continued with a Proposition U, another anti-growth ballot measure aimed at commercial and industrial development. The result of Prop U was to concentrate jobs in intense pockets like Westwood, Century City, and Downtown. White homeowner entitlement was cemented against lower-income communities of color on one side and against private capital on the other. This, of course, is the most critical segment of the YIMBY historical narrative, a launch point for several decades of minimal housing construction and an as result, rising urban core housing prices. But the history of our cities and of Los Angeles does not end here.

The next great shift in metropolitan history was the “conquest of cool.” Those people who had the option to suburbanize but chose to remain urban participated in bohemian communities, which ran counter culture to the seemingly flat, bland worlds of downtown office towers and tract-home suburbs. As Suleiman Osman describes in The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn, places like Brooklyn Heights (and its cousin, Silver Lake) offered a sense of small-scale authenticity and vibrancy that couldn’t be found elsewhere.

The godmother of these “new urbanists” was Jane Jacobs. Jacobs certainly opened my eyes to a new way of seeing and experiencing the dense urban environment when I read her 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Against the freeway, office-tower, and suburban-centered development that reigned after World War II, she pointed out the importance of small-scale urban life. She shared important observations about street life such as the how architecture can ensure safety by keeping a lot of eyes casually looking over a public space. She illuminated some of the failings of top-down planning as it existed in her time. Her writings were a useful corrective to mid-twentieth century redevelopment excesses, but the experiential perspective on urban life only scratched the surface of the injustices perpetuated by the large-scale urban projects she decried.

The new bohemian urbanism, consciously positioned against the mainstream and the market, was gradually integrated into them. In his book The Conquest of Cool, Thomas Frank traces the history of the “bohemian cultural style's trajectory from adversarial to hegemonic; the story of hip's mutation from native language of the alienated to that of advertising.” This was just as true for urbanism as for music or any other form of cultural expression and experience. There was genuine interest in sharing racially, socioeconomically, and culturally diverse neighborhoods and public spaces among those who stayed even though they had the privilege to leave. But racial inequality, metropolitan segregation, and market dynamics combined to drive far wider changes.

Long before regional-level shortages of housing existed, young white adults in pursuit of hipness (including many from well-off families) were attracted to neighborhoods near the urban core by the low cost of rents and the countercultural sense of cool. Not able to afford places like Westside or uninterested in its lack of dense vibrancy, the children of those who benefited from subsidized suburbanization began a process of settling in formerly neglected neighborhoods. Private capital, seeing opportunities to profit, returned to formerly disinvested neighborhoods serve this nascent affluent population. And thus a cycle of urban redevelopment began that continues to this day.

As neighborhood after neighborhood turned “edgy, but interesting” and then “cool and safe,” real estate investors saw the promise of safe returns. Relatively low land values combined with the expectation of rising property values spurred speculation, physical upgrading, and intentional efforts to push out existing residents. The new amenities, along with the influx of the “right” kind of people catalyzed further increases in land and housing prices.

The initial agents of gentrification were pushed to adjacent poor and working-class neighborhoods and the cycle began all over again. Of course, the people initially left behind and then pushed out didn’t have the capital to profit from rising property values. Instead, investors were able to profit from the difference between present and expected future value.

Municipal governments, eager for visible signs of “urban revitalization” and new tax revenue, did what they could to encourage this process, investing public dollars in infrastructure improvements and increased services and policing. Transit often served as tool for this purpose, a marketable amenity and a sign of “cool” urban living. As the neighborhood became firmly middle-class and then affluent, even bigger private capital flowed in. As living in core urban neighborhoods becomes part of mainstream culture (from “Seinfeld” and “Friends” to “Sex and the City” and “Girls”) these places become even more desirable, especially for rising generations of young people.

It is no coincidence that gentrified and now gentrifying areas like Echo Park, Venice, and Boyle Heights were the ones that had been systematically redlined and disinvested from. The correlation between the red areas of the HOLC map of L.A. and current “hot” neighborhoods is uncanny. There is a lot of money to be made by moving the color line.

* * *

The cruel irony of America’s metropolitan history is that the communities that were systemically divested from are now being harmed again, once again partially fueled by booster dreams. Crueler still is the fact that those YIMBYs with power and privilege are now telling the folks who have suffered most that they must trust that this time a more liberated real estate market will produce a equitable outcome for them.

Housing cannot be understood in isolation, detached from questions of how the economy works and how its benefits are distributed unequally across the population. When YIMBYs and developers protest that private housing construction shouldn’t be taxed or mandated to foster equity, they neglect the fact that housing construction and the private market have not merely echoed social inequalities — they have perpetuated and deepened those inequalities. This is especially true today when an influx of large-scale investment capital contributes to rising housing asset and rental prices.

The housing justice movement by and large understands the concept of supply and demand, despite YIMBY's complaints otherwise. Yet housing justice movements — part of a long line of “housers” and progressives interested in equitable transit-oriented development — are able to see that left alone to produce housing, the market will not meet the needs of a large proportion of the population. That was true in the late 19th century, as slums emerged. It was true in the mid-twentieth century heyday of redlining and subsidized suburbanization and urban redevelopment. And it is true today when redlining and other forms of discrimination and exploitation of the less privileged continue. The market alone does not produce good outcomes for communities who were denied the ability to accumulate wealth in previous housing booms, through redlining and because of an overall economy that has grown increasingly unequal over the last four decades.

Ignorance of this history leads many YIMBYs to perplexity and frustration over why housing justice advocates are so stubborn in advocating for linking density and reduced parking requirements to the creation of affordable housing, good jobs, and other community benefits. It is especially grating for housing justice advocates when white male YIMBYs — some with little actual expertise — insist on plan-splaining to organizations — many of whom led by women and people of color and with dozens of expert planners, scholars, and lawyers on their collective staffs — about how the housing market actually works.

Meanwhile research from scholars like Miriam Zuk and others shows that exclusively market-rate development near transit will lead to a displacement of low-income people who are core transit-riders. Increased supply concentrated in “hot” neighborhoods is likely to drive displacement in the short-term while only reducing housing costs over the long-term at the regional scale. That’s cold comfort for families suffering the economic downsides of longer able to commute to work via transit, while still paying high rents on the suburban outskirts for many years to come.

The good news is that there is a viable alternative to the dogma of laissez faire, the historical reality of government facilitating private investments that moves to the color line to benefit the largely white middle-class, and the obstinancy of privileged homeowners. The tradition stretching from the “housers” to the regional planners to today’s equitable development movement offers a third way to ensuring adequate supply of housing affordable to all levels of the community.

It’s a tradition which has never been able to fully realize its promise, thanks to the power of racism, homeowner privilege, wealth inequality, and investor class influence but it is finally gaining steam, with notable victories like Measure JJJ and the enactment of the People’s Plan in South LA. As ACT-LA’s letter notes, the “LA City Council approved in November an area-wide no net loss program throughout South L.A. that incorporates various anti-displacement and affordable housing replacement policies that align with the incentive programs tied to transit corridors.”

It is outrageous that Wiener’s S.B. 827 is poised to override these initiatives that are finally coming to fruition after decades of struggle by historically disadvantaged communities to go beyond a seat at the table and finally set the agenda for equitable development. Laissez faire, subsidized private construction along racial lines, and NIMBYism have all failed. It is time for California state policy to build upon housing justice wins that prioritize equitable development and input from those who have been marginalized by historical planning patterns.

I believe there is an important place for progressive YIMBYs as allies of the housing justice movement. Creating a real coalition to achieve shared goals beyond simply stopping misguided proposals like Measure S is possible. Progress requires listening early and often to housing justice advocates. It’s not enough for YIMBY leaders and groups to initiate dialogue; they have to stop insisting they have all the answers. It would be helpful if they acknowledged the history of market failure and government-enabled discrimination by private capital, in addition to the problems of anti-density laws. It would useful to begin with building on the housing justice and equitable development policies that were developed out of the most impacted communities. It would be productive to learn from community experiences in struggling against waves of disinvestment and displacement that have acted like the urban equivalent of the fires and ensuing mudsides that are one-two punches to our fragile Southern California landscape.

Progress will take a willingness to focus on increasing supply in wealthier areas like Santa Monica and Beverly Hills, while not accepting policies that accelerate luxury development in poorer ones, with no provisions for stabilizing and creating affordable units. A bill like S.B. 827 that automatically upzones near transit is far more likely to impact historically disinvested neighborhoods in the urban core than the affluent single-family areas so frequently cited by the bill’s advocates. Claiming that it also up-zones these latter areas is not good enough. More profoundly, YIMBYs would do well to understand that unilaterally setting the year’s housing agenda with a bill like S.B. 827 and then hectoring potential allies to ‘fall in line’ without debate and withhold a public position until amendments come out is not constructive.

Progress will take a willingness by YIMBYs to stop opposing almost everything L.A.’s broad coalition of equitable transit-oriented development groups support (e.g. linkage fees, Measure JJJ, community plan updates that tie density increases to equity provisions) and to acknowledge that increasing supply in the aggregate isn’t enough to improve the situation for people below the median income.

Progress will take a willingness by YIMBYs to craft legislation that centers the proposals of housing justice groups and then adds components to increase aggregate housing supply. Investments in stabilizing and creating affordable housing, as well as support for good local jobs and other community benefits, can’t be afterthoughts to help win passage of legislation to increase infill development, likely to be discarded in later deal-making if recent legislative maneuvering is any guide. It is not cynical to be skeptical. It’s simple realism for those who know their history and how politics still works today.

Our history makes evident that trusting the word of those who promise to help marginalized communities after the middle-class is taken care of is a fool’s decision. We must craft solutions that meet the needs of all of our struggling communities, tethering benefits for the middle class to the most marginalized, and yoking together our political interests in the process and building a political coalition that ensures the rich don’t get richer as the poor get poorer.

David Levitus earned his Ph.D. at USC with a focus on the history of cities, policy, and politics in the United States. At NYU, he majored in Economics and History. He is the Founder and Executive Director of L.A. Forward and the host of the L.A. Forwards & Backwards Podcast.