During the public comment on the South and Southeast Community Plans this past November 22, Daniel Wright of the Silverstein Law Firm (most recently notable for the firm's support for Measure S and aid in stalling a project aimed at housing homeless residents in Boyle Heights) stood before the city council and accused Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson of hurting development in his community by supporting the effort to reclaim the vacant lots at Vermont and Manchester via eminent domain.

My ears perked up.

Not just because the comment was apropos of nothing and was quickly shut down by Councilmember José Huizar for being off-topic. But because it offered the first glimmer of hope that the stasis surrounding the development of those lots might finally be broken. Steven Sharp's post on Urbanize L.A. today breaking news about the county's effort to see the lots condemned so they can be reclaimed suggests real change may finally be on the horizon.

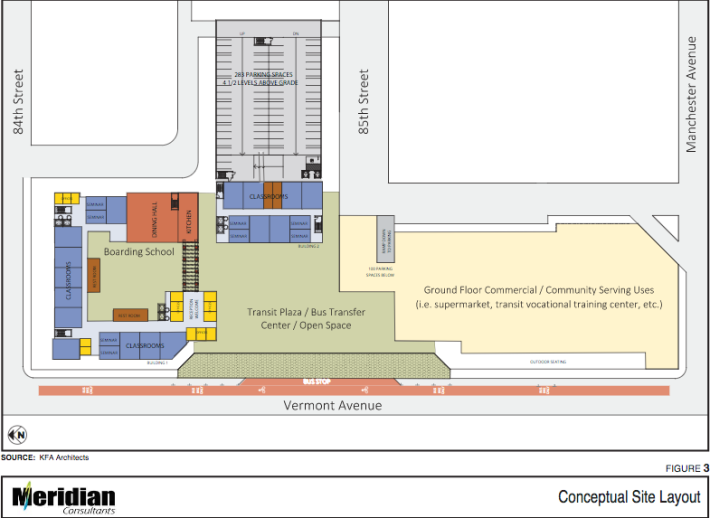

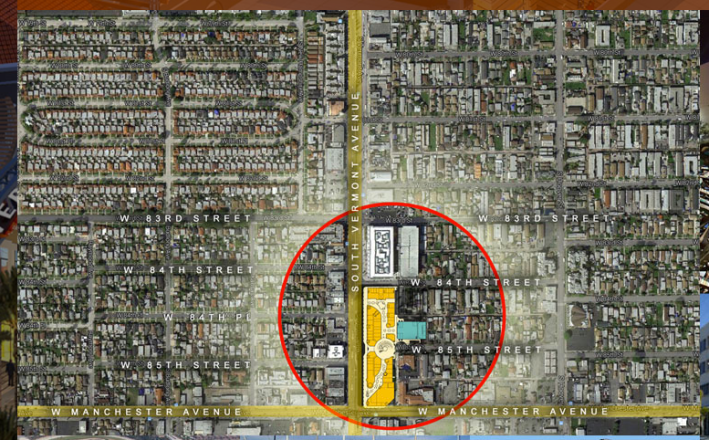

Were the County to finally acquire the property, it would be transformed into a mixed-use development including a six-story structure housing 180 affordable one-, two-, and three-bedroom units, a first-of-its-kind-in-the-area public charter boarding school aimed at giving area students a supportive 24-hour learning environment (including a six-story structure housing 200 dorm rooms and 20 faculty apartments), a career technical education center, neighborhood-serving retail (potentially including a supermarket), community spaces, and a transit plaza.

The $15,700,800 needed to acquire the property for the Vermont and Manchester Transit Priority Joint Development Project - so dubbed because of the potential of the County to partner with the Metropolitan Transit Authority to "create a center to train a new generation of employees for careers in mass transit" while serving as a "sustainable" and "affordable" transit-oriented hub - would come from the Second Supervisorial District Prop A Local Return Transit Program ($11,900,000) and that district's capital fund budget ($3,800,800).

The County's proposal doesn't make the acquisition of the property or the project a done deal. The Board of Supervisors must first find the project exempt from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), adopt the Resolution of Necessity authorizing the commencement of an eminent domain action, instruct the County Counsel to file a condemnation action, and then approve the project and the transfer of funds. [The board will consider this project Tuesday, December 5]

Only then will the wrestling with the developer and, it appears, the Silverstein firm, over eminent domain begin in earnest.

If Wright's public comments and both Silverstein's and developer Eli Sasson's track records are anything to go by, then that fight will likely be drawn out and messy.

Considering the extent to which the lots at Vermont and Manchester have held the community hostage to blight for over 25 years, that would be a deeply unfortunate outcome.

The site of a former swap meet that burned to the ground in 1992 (see photo), the lots are more than a testament to how hard the neighborhood was hit by the unrest and how slow it has been to recover. They have come to symbolize the many barriers the whole of South Central has faced in taking control of its own destiny.

After the last fires had finally stopped smoldering in 1992, a young resident named Dana Gilbert (above) had walked the lots with then-mayor Tom Bradley, contemplating how the community might benefit from the effort to rebuild the area.

But too many of the owners of burned-out properties were not from the area, meaning they had no personal stake in it nor would they be personally affected if the properties were allowed to stand blighted for decades. Said parcel owners were so slow to address the mess on their lots, said Gilbert, that he had been able to make extra income selling scrap metal scavenged from burned out structures in the community for almost four years following the uprising.

Sasson - the owner of the properties at Vermont and Manchester - proved no exception. The shopping center projects he proposed for the site - ranging from too modest to "impossibly grandiose" - never seemed to indicate a true commitment to the community or to seeing the proposed projects actually flourish. Sasson himself blamed the inconsistencies and delays on the changing whims of the city.

The truth is more complicated.

It took several years for Sasson to gain full site control - a few smaller lots within the 8400 and 8500 blocks of Vermont had been owned by others, including his own brother. Around the time Sasson got site control in 2006, he shed the lots in the 8300 block. In doing so, he made way for construction of a social services building while simultaneously limiting the possibility that a truly grand shopping center attracting the kinds of quality retail and services the community was clamoring for would ever be built on the remaining parcel.

His insistence that the city help finance his project to the tune of as much as $32 million while ignoring area business owners' efforts to engage him about moving into his proposed development didn't sit particularly well with stakeholders, either.

Responding to community frustrations (and the fact that Sasson now had full site control), the embattled Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) finally moved to condemn the lots at 8400 and 8500 Vermont and reclaim them via eminent domain in April of 2008.

The agency was soon stymied by Sasson’s disruptive pre-trial tactics (see p. 2, here) and his asking price of $25.5 million, which was significantly higher than the CRA’s $9.1 million appraisal of the property. Four years later, the deal would fall apart before the proceedings could reach a conclusion, thwarted by the 2012 dissolution of the CRA.

The fate of the lots was in limbo yet again.

Three years later, on the 23rd anniversary of the 1992 unrest, Sasson surprised many in the community by holding a ground-breaking ceremony for the Vermont Entertainment Village.

The shiny new open-air mall, outgoing City Councilmember Bernard Parks and other dignitaries proclaimed, would anchor positive growth in the South Los Angeles neighborhoods around Vermont and Manchester and transform them into a "destination."

Residents who had received postcards about the ground-breaking ceremony gathered outside the fence around the lot only to be denied entry to the official festivities. All expressed hope that, this time, something would happen there. But given that they were also accustomed to hearing promises that were not kept, many also said they'd only believe it was real once they saw construction underway.

They were right to be skeptical.

Two and a half years on, it is abundantly clear that the plans are going nowhere and that the ground-breaking was little more than a glorified send-off for the termed-out Parks.

When questioned about the delays on the project in the spring of 2016, Sasson told the L.A. Times that some of the holdups involved complications due to the need to reroute electrical wiring (something the city disputed).

I had also called Sasson while working on my update on the project that spring, but had been unable to get a response.

At least, at first.

I got a strange voicemail from him months later, while I was out of town just after Thanksgiving. When I reached him in early December, I listened in stunned silence while he ranted for well over an hour and a half about how he misunderstood he was and how the city was trying to squeeze him for everything he had.

The CRA (or the "Community Destroying Agency," as he called it) and the city had done him dirty, throwing "property balls" at him "like a dog" and, he claimed, demanding $4 million from him to reroute the wiring and get the necessary permits to be able to build.

"I don't sleep at night. I don't dream at night," he declared at one point, suggesting that trying to move the project forward had disrupted his life.

A face-to-face with the councilmember had fallen through, he had had to look for funding in China because he couldn't get it from Bank of America, people didn't seem to want to do the right thing, and he was being harassed because the lots were not cleaned every day, he complained.

"If someone comes and can do better, have them come do [it]," he said bitterly of the community's frustration with his unwillingness to give up the property. "Why [does] nobody call me [in support of making his project go through]?"

"I'm trying to do the best I can to make it a gateway to L.A.," he continued. "I want to build here because I want to give back. I have the guts to do that. Yeah, I have some ego ... I can't just do shitty work ... Everything has to be [a] museum piece to me."

"Nobody calls me, but I can talk to you," he said again, nonplussed when I reminded him I had called him several times in March of that year. "A thousand people need to call me. Only you call me. Nobody call[s] me ... I've become a victim."

Earlier that year, his then-Chief Operating Officer had told me that Sasson was just very bad at telling his own story - something which made it easy for him to be painted as the villain in his dealings with the city.

After hanging up the phone with him in December, the only thing I was clear about was that his poor storytelling abilities were really the least of the problems at hand.

Instead, what was clear was that he had yoked himself to a poorly-conceived mall project that served an imagined community from a different era - not the one that was actually there and which was in desperate need of community-serving investment, retail, and services. The theater of it all seemed to be what interested him. At one point he even rambled on about mahogany and only wanting to use the best materials for the project before suggesting that, since I had called him, we could make a movie about all the city had put him through.

How that approach to development could possibly serve one of South L.A.'s neediest communities was and continues to remain a mystery to me.

It is deeply disheartening that twenty-five years after residents railed against the discrimination and disenfranchisement imposed upon their community their fates continue to be at the mercy of so many who have no real stake in their well-being. The project the County is proposing could go a long way toward mitigating some of the harm that's been done.

Hopefully the parties involved will take that into consideration as the process moves forward.

For more details on the proposed project, see the Resolution of Necessity. The The County Board of Supervisors will consider this project Tuesday, December 5 at 9:30 a.m. To listen live to the hearing, click here.

*Thanks again to Steven Sharp of Urbanize L.A. for the heads up this morning.