Late last year, Metro finished pedestrian and other safety upgrades to eight intersections along the Blue Line.

The improvements were part of the $1.1 billion's worth of upgrades to the line that have been underway since 2014. Thus far, overhead lines have been replaced, platforms have been improved, and pedestrian access has been made safer in Compton and Long Beach. Pending improvements include the replacement of the 27-year-old trains, changes to signalization to shorten travel times to downtown L.A. by 5 to 10 minutes, and finishing pedestrian improvements throughout South L.A. and the County [Other short-term fixes proposed to make merging of the Expo and Blue Lines smoother are separate but also much needed.]

The pedestrian improvements finally taking shape at the remaining 19 intersections - 12 of which are in South L.A. - have been in the works for some time and continue to prove challenging.

I first wrote about them in 2013, after watching Vijay Khawani, Director for Corporate Safety, page through a thick packet of possible reconfigurations for intersections where Blue Line tracks paralleled one or two sets of Union Pacific Railroad's (UPRR) freight tracks.

The fact that Long Beach Avenue was split by four sets of parallel tracks complicated things in South L.A., Khawani told me then.

For one, there wasn't much room to implement fixes like pedestrian swing gates. Without significant interventions to many of the intersections and their crossings, he suggested, wheelchair-bound pedestrians might have to roll back into the intersection just to open such a gate.

Where Metro is adding new active pedestrian gates but is unable to widen narrow spaces, it is lengthening them to create room for pedestrians to maneuver more easily (and ensure ADA compliance).

Above, Metro has added concrete slabs to the crossing at 48th Street. The slabs extend to the right on the far tracks (where the yellow tape is). According to plans for the intersection (below), there should also be some extension of paving along the UPRR tracks.

The finished product will look something like the image below from 92nd and Graham - a pedestrian swing gate, a lengthened crossing, and an active pedestrian gate (arm that lowers) that allows for straight-ahead passage when the path is clear.

Significantly, the improvements are going in on all four corners of each intersection, and extending to the far curbs on each side along Long Beach Avenue. Metro even went so far as to use eminent domain to acquire corner space at Florence in order to be able to implement pedestrian gates there.

At present, where pedestrian barriers exist, they are only on the Metro side.

This has made it easy for pedestrians and cyclists to move onto the tracks while trains approached. Notably, this has also been considered to blame in a number of collisions, including that of middle-schooler Gilberto Reynaga, killed in 1999 when he clambered over a stopped freight train at 55th and Long Beach Ave. only to be hit by a passing Blue Line train. [See more in-depth discussion of collisions, safety issues here and here.]

The lack of infrastructure, it turns out, was also by design, Khawani informed me: Union Pacific constituted the other major hurdle to upgrades.

Fearing that allowing Metro to install anything more than the most basic of safety protections alongside UPRR’s right-of-way (ROW) would trigger an avalanche of demands for them to do the same along the thousands of miles of tracks they manage across the country, UPRR consistently pushed back against Metro's plans to improve intersections where UPRR tracks paralleled the Blue Line. So much so that when the plan to make pedestrian improvements was first floated in 2012 (in response to an uptick in collisions along the Blue Line that year), the project was limited to targeting 19 intersections and implementing just 11 active pedestrian gates.

The struggle to get UPRR to take pedestrian safety seriously can be seen in Metro’s Blue Line Safety Task Force report from November of 2012. Where input from Metro, LADOT, the City of Long Beach, and the City of L.A. seemed to indicate a commitment to the installation of upgrades at the intersections hosting multiple sets of tracks, UPRR’s comments suggested otherwise. [Comments begin on p. 6.]

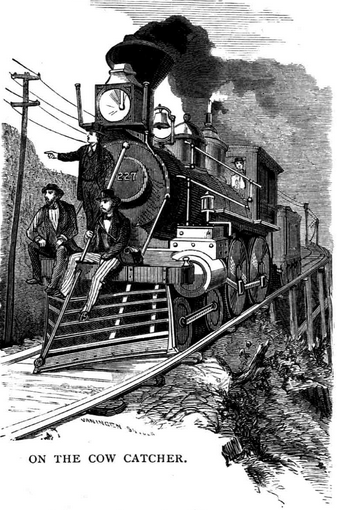

Some of the UPRR comments about potential upgrades contained the complaints that people would probably tamper with pedestrian gates (rendering them inoperable) or ignore them altogether (rendering them a waste). Other comments, apparently made in all seriousness, endorsed the notion that Metro look into “cowcatchers” for the front of its trains so as to minimize pedestrian deaths (at right). And UPRR reiterated several times that it expected to be reimbursed for all costs related to the design, construction, and maintenance of any infrastructure on its side of the tracks.

It seemed that UPRR would have its way until about September of 2014, when the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) intervened. The CPUC ultimately required not only that UPRR implement the same upgrades on both sides of the ROW, but that Metro go the full distance in overhauling all 27 intersections to install the full range of safety measures currently required on new construction.

Doing so raised the costs of project substantially and further slowed it down. Instead of sending out the RFP as planned in 2013, Metro had to return to the drawing board to design a whole new set of interventions. The cost for the project, initially estimated at just under $8 million, ballooned to $30,175,000. [Find the cost breakdown here.]

Despite the fact that the Blue Line has, with 51 fatalities between 2010 and early 2015, proven three times more deadly than the Expo and Pasadena Gold Lines combined, Metro's own 2015 discussion of the impact of these safety improvements is rather cold-hearted. The reason for this, it appears, is due to Federal Department of Transportation guidelines on how to evaluate policy alternatives and calculate the value of statistical lives saved. But it makes for a pretty awful read.

Essentially, Metro notes that the

costs of defense and payments to injured pedestrians or survivors have been very small, because of the comparative negligence of decedents and injured parties as well as existing statutory immunities for rail design. The average annual costs total $679,448, with $310,424 spent on Workers’ Compensation and $369,024 spent on third parties. These costs include legal expenses, payments to third parties, temporary and permanent disability payments to Metro workers, and medical costs, but exclude other unallocated expenses such as Metro staff time to administer or investigate the incident, Sheriff costs, and others. Therefore, expected financial benefits to Metro from safety improvements on the [Blue Line] today are relatively small, although risks are growing.

There are other benefits to reducing fatal and non-fatal pedestrian collisions, too, Metro adds, including "fewer service disruptions, the opportunity cost of investigation and administration and the significant expense of providing medical care and disability benefits to highly traumatized rail operators, some of whom never return to work."

In short, according to the calculations found in attachment D, available here, saving lives will save the city approximately $202 million over 25 years.

This project is not about being warm and fuzzy, in other words.

So be it.

Cold-hearted or not, the takeaway is that Metro will not be relying on cowcatchers and, some time later this year, the communities along the Blue Line will finally have the safety improvements they should have had all along. And that is a good thing.