Listening to the City Planning Commission vote in favor - albeit somewhat reluctantly - of moving forward on the regressive amendments to the Mobility Plan 2035 this morning, I felt my heart sink.

With recommendations the City Council approve amendments that a) remove Westwood Boulevard (between LeConte and Ohio) and approximately seven miles of Central Avenue from the Bicycle Enhanced Network (BEN), b) substitute those routes with less direct and less-likely-to-be-used parallel streets (Gayley and Midvale in Westwood and Avalon and San Pedro in South L.A.), and c) allow for more north-south corridor substitutions in the future, where deemed prudent, the city of Los Angeles officially moved closer to taking a significant step back from its commitment to building a safer and more accessible city for all. [See the CPC agenda and staff report.]

Worse still, it was all happening in the guise of greater "safety" and mobility as defined by people who appeared to care very little about either for people other than themselves or their own narrow interests.

That hypocrisy was perhaps best exemplified by the Westwood contingent of homeowners who now were masquerading as bus huggers. Which was truly bizarre, considering that just last year, when Fix the City and their Westside supporters launched their lawsuit against the Mobility Plan, they were decidedly anti-transit and anti-options in their approach. The group's president had ranted about how the city “want[ed] to make driving our cars unbearable by stealing traffic lanes from us on major streets and giving those stolen lanes to bike riders and buses.” Laura Lake, the group's secretary, had told the L.A. Times that safer streets and more transportation options could only lead to greater tailpipe emissions, greater congestion, first responders getting trapped in traffic more often (implying more death and destruction), and greater sacrifices made by people whose schedules would be so disrupted that they would lose untold hours that would otherwise have been spent working or with their families.

Today, Lake had completely changed her tune. Now she was telling the commissioners that she was deeply concerned about the more than 900 buses traveling along Westwood every day. If those buses were to get stuck behind a bicyclist, she posited, thousands of bus riders could be impeded from getting to work or school.

Clearly unencumbered by the idea that the whole point of having separate lanes for bikes and buses is to keep them from having to cross each others' paths and that the only ones blocking buses in such a scenario would be private vehicles, she declared she only hoped to benefit "the greater good."

Other Westwood advocates that stood to speak took their lead from the backwards logic regularly deployed by Councilmember Paul Koretz regarding bike lanes, arguing busy streets with no bike infrastructure were dangerous for cyclists and therefore better infrastructure must be avoided at all costs.

"It's really simple," declared Stephen Resnick, president of the Westwood Homeowners Association. Substituting the less-busy Gayley and Midvale streets for Westwood on the bicycle network was about nothing more than "safety" and "transportation."

Barbara Broide, another Westwood HOA president, argued bikes on Westwood would deter people trying to connect to the Expo Line via bus and wondered how people could possibly feel safe riding bikes alongside hundreds of buses anyways (which of course they don't, which is why they have clamored for the bike lane). Stakeholder Debbie Nussbaum warned against bike lanes on busy streets in general, proclaiming they ran the risk of giving people a false sense of security.

The nonsense was too much for Sean Meredith - a commuter who, unlike those that had just spoken, regularly cycles through the area. Westwood provided a direct route to the Expo Line, the most direct line to UCLA, and was actually the safest route, he said, explaining the more narrow nature of the substitute streets and the many parked cars there made for poor visibility and more unsafe conditions for cyclists.

If you really want buses to be able to travel Westwood freely, he argued, put in a bike lane so the bikes can get out of the way.

His comments were echoed by UCLA planning analyst Michael King, who also argued that while adding in substitute corridors to the BEN was fine, removing them from the Plan was counterproductive. Bonnie Bentzin, UCLA’s deputy chief sustainability officer and also a bike commuter, reiterated her support for a Westwood bike lane, reminding the commission that the decision to substitute Midvale and Gayley for Westwood had been made without any investigation into whether they provided a viable option in the first place.

Speaking in perhaps the plainest terms, LMU professor and bike commuter Michael Brodsky argued there was no point in implementing lanes that cyclists would not use just because politicians preferred them. The Plan, he stressed, was about making transportation safer and more accessible for everyone, not just motorists. And streets that were safer for bikes were, by default, safer for pedestrians, motorists, and everyone in between.

The idea that lanes should go where people are most likely to use them - and actually need them - applies nowhere more clearly than along the 7.2 miles of Central Avenue linking Watts to Little Tokyo.

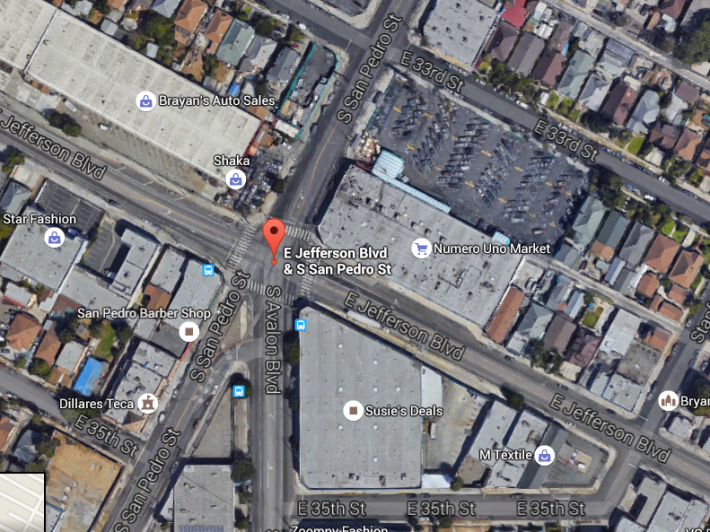

As we have documented here, Central Avenue is the most highly trafficked street by bicycle commuters in all of South Los Angeles, if not the entire city. The vast majority of the commuters are working-class Latinos and students who have few transportation alternatives available to them. They are also people for whom side streets are largely off limits (due to the way gang territories are divided up and enforced) and for whom a street like Avalon - a full half-mile away - is so out of the way as be of little use. And they are people for whom a five-way intersection, like the one where San Pedro and Avalon split, is so intimidating that they might try to avoid it altogether. [The proposed substitute lanes would be placed on Avalon, south of Jefferson, and San Pedro, north of it.]

As Jefferson High School student Adalberto Juarez explained during his testimony, the city needed to understand that a lot of the people using Central Avenue were families who were desperate for healthier options. His family had a history of diabetes, he said, and his dad wanted to do things like take Juarez' sister out on his bike, but often felt that the risk was just too high.

Moreover, Juarez continued, many of the people using the street were unaccompanied kids whose mothers regularly sent them on quick errands. Their trips were hyper-local and patronized local businesses, making it highly unlikely those kids would go two full miles out of their way just to go 3/4 of a mile up the street and back.

Instead, that kid would be more likely to ride on the sidewalk, as the vast majority of cyclists do now. And if Councilmember Curren Price goes ahead with his plan to expand the sidewalks - as is likely, given his and the city's top-down approach in the Great Streets planning process, the mayor's February, 2016, letter of support for South L.A.'s Promise Zone touting the creation of a pedestrian zone, and the request that most of the length of Central be made part of the Pedestrian Enhanced District - we can expect that sidewalk riding will continue to be a staple on the avenue.

That's a problem.

As JHS student Sabina Cervantes explained during her testimony, cyclists often crash into pedestrians on the sidewalk. It is a long-standing complaint of many of the residents and businesses along the corridor, especially those that cater to families. "Every time I walk to the store with my 4-year-old brother," she said, "I have to be very cautious [and look out] for them."

What she didn't want, she said, was for the people of South Central to have to continue to adjust to being given amenities that did not fit their needs. She and Juarez had conducted surveys as part of their work with the National Health Foundation and they had found that bike lanes along Central Avenue were seen as part of a healthy community and as infrastructure that could protect friends and family.

"I was there, and I did [the research] myself," she concluded. "If we want to make streets safer, both pedestrians and cyclists must be provided with their appropriate lanes."

Many of the commissioners, it appeared, did not disagree.

As they weighed the testimony against the amendments, questions arose regarding the "removal" of lanes from the Plan. Would removing them now preclude those corridors from being subject to study for bike lanes in the future?

No, came the answer.

Satisfied that this meant that the amendments did not significantly alter the Plan, and wishing to have the Plan finally see the light of day after all of these delays, the commissioners voted to recommend that City Council adopt the network and text changes to the Plan outlined here and that the City Council adopt the changes to the BEN and PED as outlined in the Staff Recommendation Report.

Renee Dake Wilson was the only commissioner to vote "no" with regard to recommending adoption of the network and text changes. But several others, including Robert Ahn, Dana Perlman, Samantha Millman, and Veronica Padilla-Campos, expressed their support for the original plan to put bike lanes on Westwood and Central and reiterated that their willingness to sign off on the changes was linked to the ability of planners to revisit the "removed" routes in the future.