Last week, United States District Judge George Wu issued a ruling [PDF] in Beverly Hills' legal battles against Metro's plans to tunnel the Purple Line subway beneath Beverly Hills High School.

The Beverly Hills Courier portrayed the ruling as a victory for Beverly Hills in that Judge Wu chided subway proponents for "not properly considering the environmental effects of running a tunnel through an area riddled with abandoned oil wells and pockets of potentially explosive methane gas."

Though the judge sided with Beverly Hills, agreeing that the subway environmental studies did not fulfill all the requirements of the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), the decision is more of a split ruling with some of Beverly Hills' winning points more nitpicky than substantive.

There are a couple of lawsuits with multiple parties involved. The plaintiffs include the city of Beverly Hills and the Beverly Hills Unified School District. The defendants include Metro and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA). For the purposes of this article, SBLA simplifies the parties to "Beverly Hills" against "Metro."

The ruling last week is in the federal court case; Metro won the state court case last year.

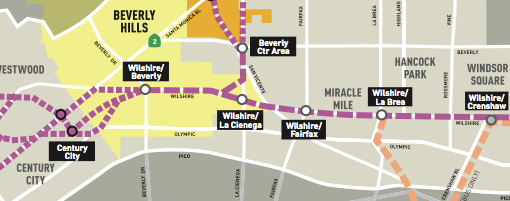

The lawsuit primarily centers on Beverly Hills' criticism of Metro's decision to relocate the planned Century City stop from Santa Monica Boulevard to Constellation Boulevard.

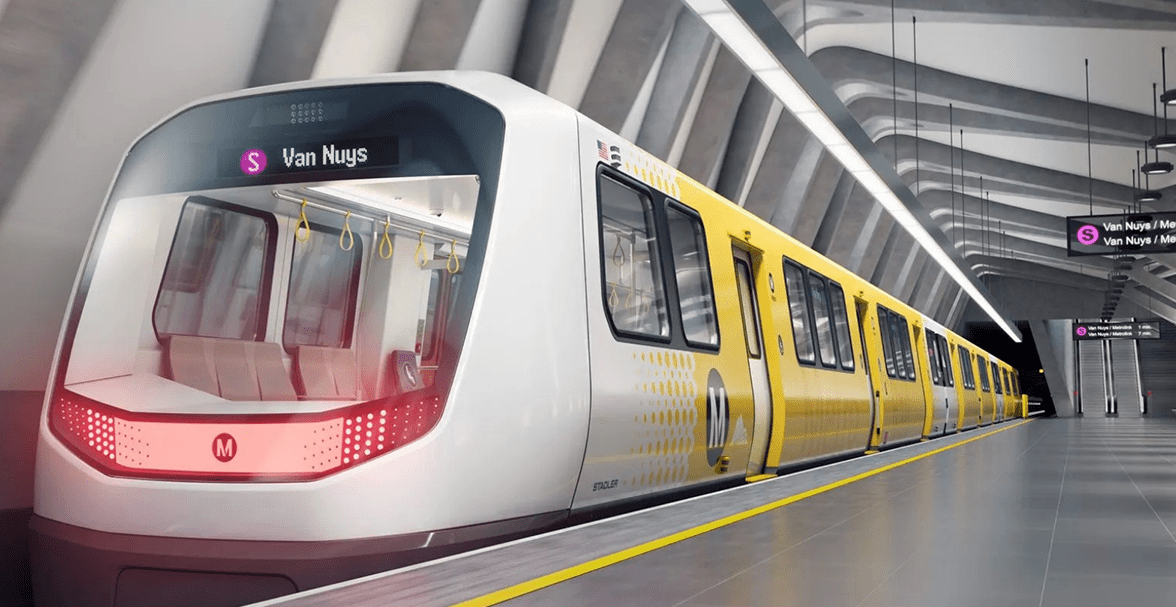

Metro studied numerous subway alignments, and ultimately chose a route that places the Century City station at the intersection of Constellation Boulevard and Avenue of the Stars. Though Constellation and Santa Monica are one block apart, Metro found that Santa Monica Boulevard would not work due to earthquake faults. The Constellation alignment effectively necessitates tunneling under Beverly Hills High School.

All in all, Beverly Hills raised nine issues where it asserted that Metro's environmental studies (Environmental Impact Statement - EIS) failed to meet NEPA requirements. The court sided with Beverly Hills on half of those issues. In effect, though, Beverly Hills effectively only needs to prevail on one issue to find that Metro failed NEPA.

The conclusion of the 217-page ruling [PDF] reads:

The Court concludes that [Metro] failed its disclosure/discussion obligations ... in connection with [Beverly Hills'] comments concerning the effects of tunneling through gassy ground and the risk of explosions; that it failed its disclosure obligations regarding incomplete information concerning seismic issues; and that it should have issued [additional environmental studies]. The Court also concludes that [Metro] failed to properly assess “use” of [Beverly Hills] High School under [recreational land law] due to the planned tunneling. In all other respects, the Court rules in favor of [Metro].

Metro, via spokesperson Dave Sotero, issued a statement on the ruling:

After a thorough review, Metro concludes that Judge Wu’s tentative rulings uphold the approved plans to build the Century City subway station at Constellation and to tunnel safely beneath Beverly Hills High School. Some of the findings are procedural, requiring the FTA to perform additional environmental analysis and provide a further opportunity for public comment. The majority of extensive environmental work was deemed sound. If the ruling holds, Metro will support FTA in meeting these additional procedural requirements. Time is of the essence. Any significant delay resulting from this case could jeopardize the timely delivery of this critically important transit project for all L.A. County residents.

After the jump are summaries of the nine specific areas of dispute in the lawsuit. Following those are possible next steps in the case.

1 - Air Quality and Public Health

Beverly Hills asserted that Metro's construction-related emissions air quality analysis was insufficient because the analysis did not account for local air quality, only regional.

The judge issued a mixed ruling on this point. It found that Metro "did not act in an arbitrary or capricious manner" considering air quality impacts. But, in regards to public health, the judge sided with Beverly Hills, asserting that Metro lacked "a more robust discussion of public health impacts at least insofar as NOx [nitrogen oxides air pollution] is concerned."

2 - Methane Gas and Oil Wells

Beverly Hills contended that Metro did not sufficiently take into account the potential explosive dangers of methane gases and oil wells. Metro responded that underground gases and wells might be encountered, but Metro tunneling technology allows the agency to be successful getting through these safely.

The court responded that Metro analyzed oil well locations, and that Metro can tunnel safely through areas with oil wells, but sided with Beverly Hills that Metro had not "sufficiently crossed its t’s and dotted its i’s" regarding documenting potential impacts.

3 - Alternative Routing

Beverly Hills argued that Metro failed to analyze any subway routes to Constellation Station that would avoid tunneling under Beverly Hills High School, even though Beverly Hills presented alternatives that would do this. Metro cited a number of reasons why Beverly Hills' alternatives were rejected, including that each would slow train speeds due to "sharp curves through Century City."

On this issue, the court sided with Metro echoing Metro's environmental studies: “[t]here is no reasonable tunnel alignment that does not pass under structures within the school campus,” taking into account the need “to achieve maximum safe train speeds between stations (by minimizing curves and grade differentials).” From the ruling: "In short, the Court concludes that [Metro] engaged in informed decision-making with respect to the assessment of alternatives relating to the approach to Constellation Station."

4 - Predetermined Decision

Beverly Hills asserted that Metro showed favoritism using "the environmental analysis to rationalize a decision that had already been made." Beverly Hills further accused Metro of making "a unilateral secret change of plans" in 2010 to route the Purple Line via Constellation Boulevard instead of Santa Monica Boulevard. Beverly Hills asserted that Metro manipulated seismic and ridership data to bolster its preordained choice. Metro responded that the Constellation vs. Santa Monica decision was made because technical studies showed that "there was no fault-free section along Santa Monica Boulevard that would be large enough to accommodate a station."

The court standard here is interesting: "permissible partiality" is acceptable, but it can not get in the way of the project studies taking a "hard look" at alternatives. The standard of proof is pretty high; other cases where improper pre-determination was proved involved a "binding commitment" where project proponents signed contracts in advance of finishing environmental studies.

The judge called this "a very close question" stating "the analysis certainly appears to have been slanted in one direction" but that the slant was not bad enough to clearly be full-on improper pre-determination. The ruling sided with Metro because there was no evidence of "a binding commitment of any type involved here" despite "evidence that a Constellation Station location was preferred early on and that subsequent analysis favored that preference in ways that some people and organizations found reason to criticize."

5 - Seismic Risk

Beverly Hills disputed Metro's seismic data criteria for routing the subway under Constellation Boulevard instead of Santa Monica Boulevard. Beverly Hills asserted that Metro's seismic data was incomplete, and criticized the agency for doing additional seismic studies after already approving the Constellation route. Beverly Hills asserted that Metro was not up front about uncertainties in its data. Metro asserted that environmental studies do not need "to affirmatively present every uncertainty."

The court sided with Beverly Hills on this item. The court affirmed Metro in saying that the agency's seismic risk studies were "reasonably thorough," but stated that Metro failed to make "up-front disclosures of relevant shortcomings."

6 - Re-opening Environmental Certification (NEPA)

Beverly Hills asserted that because Metro did additional seismic studies after its environmental studies were approved, the agency should have re-opened the NEPA process. According to Beverly Hills, instead Metro "simply swept problems under the rug."

The ruling sided with Beverly Hills on this, asserting that Metro should have issued additional environmental studies.

7 - Clean Air Act

Beverly Hills asserted that Metro only looked at Clean Air Act requirements pertaining to subway operations, and did not analyze air local air quality impacts for construction activities.

The court sided with Metro that its analysis was acceptable under the Clean Air Act.

8 - Public Land Usage

Federal law requires certain procedures be followed when a project impacts a park or recreation area. Beverly Hills argued that tunneling below (and constructing near) Reeves Park and Beverly Hills High School would impact recreation. Metro argued that the tunnel is far enough underground (and construction activity limited enough) that the project does not impact recreation.

Though the ruling stated that construction and the tunneling "would not substantially impair" recreation, the courts sided with Beverly Hills, stating that Metro "failed in its obligation to perform a sufficient ... analysis concerning 'use' of the High School due to the tunneling underneath it."

9 - National Historic Preservation Act

The court sided with Metro on NHPA.

What happens next?

Beverly Hills' lawsuit challenges the environmental clearance for the entire 9-mile Purple Line subway extension - from Koreatown to Westwood. The project is broken into three sections.

In 2015, Metro began construction on the first section of subway extension. The initial section costs $3 billion and extends 3.9 miles from Koreatown to just inside the Beverly Hills border. That initial extension is anticipated to open in 2023.

Beverly Hills' primary lawsuit contentions concern section two, planned to tunnel below Beverly Hills, including Beverly Hills High School. Section two is not under construction yet, but Metro has begun preliminary investigation work, with utility relocation anticipated to start soon.

Phase three will take the line from Century City to the VA Hospital in Westwood.

As of 2015, Metro expected section two to open around 2026 and phase three to open around 2035. Metro CEO Phil Washington secured USDOT approval to expedite future subway phases, in part in support of connecting rail to UCLA in time for a potential 2024 Olympics.

Last week's ruling is still preliminary. Both Metro and Beverly Hills will soon respond to the judge's preliminary document. Then on March 14 all parties are due back in court again. On that date, or soon after, the ruling will be finalized.

A settlement appears unlikely. In an interview (minute 11) with Beverly Hills View last week, former County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky described earlier settlement attempts as "dead on arrival."

If Beverly Hills and Metro are unable to come to terms, it is unlikely but theoretically possible that the judge could order the halt of the entire project, potentially including the initial section already under construction. This would be a huge mess.

A more likely, less drastic ruling would be re-opening the NEPA environmental review process, so Metro can "sufficiently cross its t’s and dot its i’s" probably before section two construction gets underway. Metro could appeal this ruling. Either a legal appeal or a re-opened NEPA process could result in delaying future subway phases. This would increase Metro's project costs - both construction and legal - without necessarily altering the subway alignment. While some in Beverly Hills might see this potential outcome as a victory, it is not clear that Metro would make any changes to the alignment already selected. With public monies wasted on extended legal battles, instead of invested in school and transportation improvements, ultimately it appears that it will be the public that loses.

With the two sides far apart, maybe newer consensus-minded Metro board members -- perhaps L.A. County Supervisor Shiela Kuehl and L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti -- could show leadership by reaching out to their Beverly Hills colleagues and trying to find some kind of face-saving middle ground.

After the March ruling, it should be clearer if the project will see any delays.