If they weren't going to let us in, said an elderly woman in Spanish, then why did they send us cards inviting us to the ceremony?

She had shown up to the groundbreaking for the Vermont Entertainment Village project at Vermont and Manchester yesterday with her daughters and their young children only to be told that it was a private ceremony. She and the other curious residents would have to stay outside the fencing while a host of dignitaries spoke about how wonderful it was to see such positive change on the 23rd anniversary of the 1992 riots and what a hard-fought victory the project represented for the community.

A man outside the fence recalled having been hired to do clean-up work on the lot several years back. Another man said he rushed down to the site on his bike after seeing mention of the groundbreaking on the news that morning. A woman standing with her daughter -- who had been born shortly after the riots -- recalled watching the swap meet burn. A young man sporting tattoos marking his affiliation said he knew it was a great day for them to begin the project because it was his birthday. And a man who had been managing the residential hotel across the street for the last 5 years said he couldn't wait for the project to be finished -- it was needed in the community.

They pored over the extra brochures I snagged for them to look at.

"Ooh, it's beautiful," "We need this," "We have been waiting so long for this," "We will be able to walk to the grocery store and won't have to go to the Ralph's [on Western and Manchester] anymore...well, you'd have to go into that Ralph's to understand..." and "Universal City Walk gonna be jealous!" were just some of the many comments in favor of the project I heard.

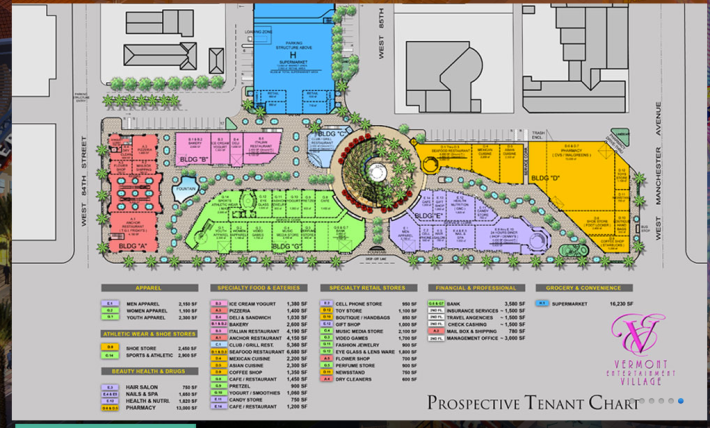

But just as common as the praise for the two-block retail destination center, promenade, and performance space were the questions about jobs and how quickly the residents could have access to them.

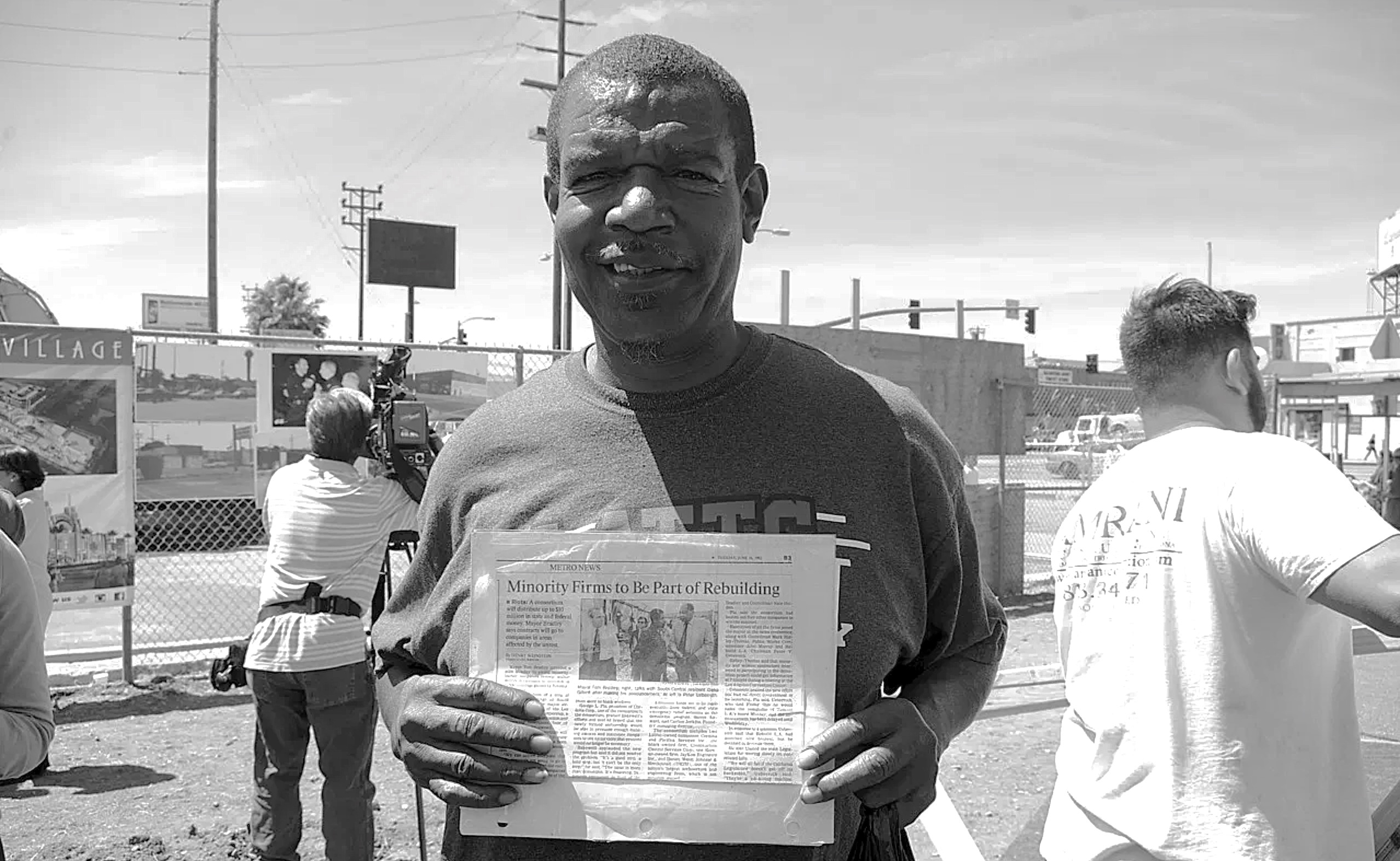

No one was more adamant about ensuring jobs went to locals than 53-year-old Dana Gilbert.

Gilbert, who had lived a block away from the site for much of his life, had shown up to the ceremony carrying his resume and a laminated article about the post-riot rebuilding effort from June of 1992 which featured a photo of him with then-Mayor Tom Bradley walking the very lot in which we were standing (see photo at top and below).

Although he was looking for that job he was promised 23 years ago, when Bradley reassured him the community would be part of the rebuilding effort, he made it clear that, "I don't care if the job doesn't go to me."

Gesturing to the surrounding neighborhood, he said, "It has to go to at least one of these young [gang members] around here. Then they will be able to tell the homies they got a job..." and that may encourage other gang members to think they could get jobs, too, or go back to school.

Making the project feel like it belonged to both black and brown residents, he felt, was important to fostering hope for the area. And hope, he knew, had long been in short supply for the neighborhood youth.

The Vermont corridor stretching south of Manchester was given the unfortunate moniker of "death alley" by an area detective for having one of the highest homicide rates in L.A. County. Much to the community's dismay, the name then became the blanket label for the community in an L.A. Times report from last January detailing the toll the violence had taken on residents. And while the alarm had been raised, it did little to stem the flow of blood over the last year.

Gilbert himself is no stranger to that reality, having been shot 6 times in two separate incidents back in the day.

"I'm half the man I used to be," he said, indicating he meant that quite literally.

Still, he managed to stay on track, working as an offset printer until he was laid off in 2007 and then attending Trade Tech to get his plumber's credentials. But it hadn't always been easy.

In the days following the riots, he recalled, "reality set in." The lots at Vermont and Manchester, holding the smoldering remains of a swap meet and other shopping centers, reminded him of the music video for "Thriller" -- smoky and spooky at night. People trying to pick up their lives and get to jobs (or even to the grocery store to get meat) found themselves immobilized because they couldn't get gas. Gas stations wouldn't allow them to fill up their gas cans, fearing the gas would be used for more rioting, and the police were making it nearly impossible for people to move from neighborhood to neighborhood.

Many, Gilbert included, began plundering burned buildings for scrap metal. But given that many of the lot owners had set up security to watch over the remains of buildings, he said, they had had to be smart about it. He and some friends would hire a girl to seduce the security guard -- she would walk past him in the day time with the promise to come back at night with dinner -- and then cut a hole in the fence, grab the metal they needed, and tie the fence back up while she kept him entertained. Lot owners were so slow to address the mess on their lots, he said, he had been able to make extra income selling scrap metal for almost four years.

Residents hadn't really had much choice to be anything other than resourceful, he said. They had all hoped for the best -- many had gotten haircuts and put on their best clothes to welcome Mayor Bradley into their community that day back in 1992 -- but the reconstruction jobs they had been promised had never materialized. So they had had to fend for themselves.

His goal yesterday was to make sure those in power knew that they couldn't get away with "building [the community] up if you're just gonna tear them down again."

The Sassony Group seemed eager to reassure Gilbert and other attendees that their intentions were good. Eli Sasson, the CEO/Founder of the Sassony Group, apparently told at least one onlooker from the community that he would be holding a job fair.

Chief Operating Officer Jennifer Dueñas said, "We are making it mandatory" for their contractors to try to hire local. They can't guarantee percentages, she said, because their financing is fully private and the contractors will be private, but they will do what they can to see that the community has the opportunity to participate in both the construction and the retail opportunities. To that end, she said, they might open a recruiting office across the street, in one of the buildings Sasson owns on that side of Vermont.

"The project is meant to uplift the community," she said. And key to that would be ensuring that the community felt ownership of the project, "...because then it will be theirs."

And there may be more to come.

"Our goal is to make Vermont-Manchester a destination point," Dueñas said when I asked about rumors Sassony would be tearing down the buildings across the street and putting in a movie theater and more retail.

Sassony is still acquiring some of the buildings (and according to the manager of one of the buildings, some of the owners are not interested in selling yet), but that larger objective seems clear, given the marketing of the project on the website (only 4 miles from downtown!), the touting of free shuttle service between USC and the Entertainment Village on the brochure, and a reference to South Los Angeles as "SOLA."

Speaking with Perry, a building manager, and some of the neighbors from across the street well after the ceremony had concluded, I heard the same kinds of comments I had heard from the onlookers to the festivities. All were impressed with the design and pleased to see that level of investment in their neighborhood -- having a safe and protected place for families and youth to walk and shop was important, they felt, given the violence and oppression around them.

Plus, it would be more convenient.

"If I lived within a block of a grocery store, I'd have a smaller refrigerator!" said one man.

But jobs were also important to them. They hoped that Sassony would choose contractors that prioritized local hiring. The young men of the area needed that -- too many were being lost. They wanted to be optimistic that the community would benefit, they said, but they had been made many promises before.

Whatever the outcome, there was one thing they knew for certain: "This is for sure going to change the neighborhood."

* * * *

For background on the $200 million project due to be completed in 2016, see this story. For more renderings, visit the Sassony Group webpage. If you have questions, comments, tips, contact sahra@streetsblog.org or follow me on twitter.