"So..." I begin, looking around the table at CALO YouthBuild students Abigail Navarro, Irvin Plata, Stephanie Olwen, and Eric Aguayo.

I am there to ask them about how the youth at this charter school -- a school whose student body is comprised of at-risk students aged 16-24 who struggled at one or more traditional high schools before eventually dropping out or being kicked out -- have managed to become among some of the most prominent community voices clamoring to be involved in the decision-making process regarding the future of Boyle Heights.

"What was it like to go back to the schools that you felt had written you off to tell their students that they needed to be more engaged in advocating for their community?"

Irvin grins.

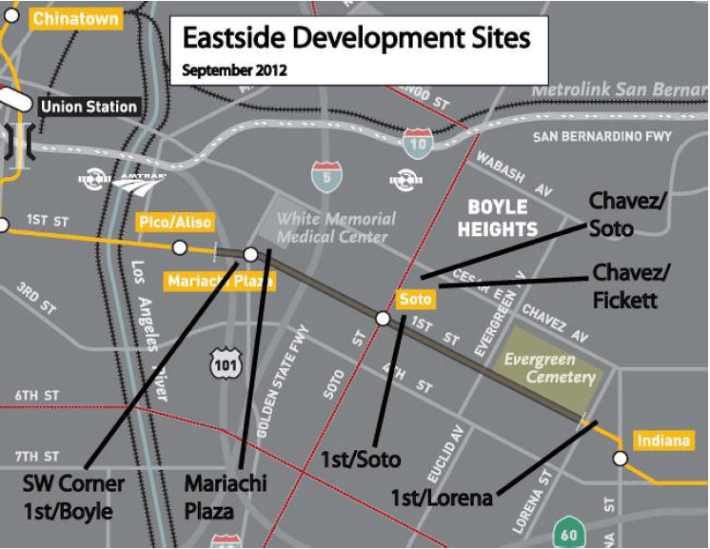

He had returned to the school he had dropped out of -- Roosevelt High -- to speak to nearly 25 classes about gentrification, affordable housing, and the development of Metro-owned lots along 1st St. and Cesar Chavez Ave. The larger goals of the outreach he, Stephanie (who visited Mendez High), and the others conducted were to encourage students to participate in the Issues Forum the YouthBuild students will be leading this afternoon and to get the students to answer the online survey* they had created exploring challenges families face in Boyle Heights.

He had been nervous at first, he says. Especially because his partner had bowed out, leaving him to do all those presentations on his own.

He was confident in the knowledge that youth participation could make a difference in the planning process, thanks to the success he and his fellow students had had in winning a 3-month extension of the community-engagement phase of the Exclusive Negotiated Agreements (ENAs) for the affordable housing projects at Metro's 1st/Soto and Cesar Chavez/Soto sites. And his confidence had been further boosted by the fact that YouthBuild's proposal for a forum on gentrification, police-community relations, and environmental justice was taken seriously by policy makers. So much so that a representative of County Supervisor Hilda Solis' office, Mynor Godoy (Boyle Heights Neighborhood Council) Max Huntsman (Inspector General of the Sheriffs Department), Patrisse Cullors (Director, Dignity and Power, Co-Founder, Black Lives Matter), and Jenna Hornstock, (Deputy Executive Officer of Countywide Planning and Development at Metro) have all agreed to participate. (RSVP to forum here.)

But Irvin was not as confident that the students he would be speaking to were going to be interested in what he had to say.

He, Abigail, Eric, and Stephanie all agreed that, back when they were struggling their way through multiple schools, they probably would have tuned out someone who came in to lecture them about the joys of community involvement in urban planning.

Tapping into the students' lived experiences and connections to the community, Irvin decided (with the help of his economics teacher and mentor, Genaro Francisco Ulloa), would be key to getting their attention.

So, Irvin made his presentations interactive. He asked students about their relationship to landmarks like Mariachi Plaza and how they would feel if those sites were to become unrecognizable or de-linked from the community's culture. He also engaged students on some of the challenges they face -- high rents and overcrowded housing, no access to jobs, mobility issues, etc. -- and tried to help them understand how developments in the area, if not designed with the community in mind, could exacerbate the struggles they were already living.

And the struggles those students are living are pretty intense.

According to the nearly 500 survey responses the YouthBuild students received, between 260 and 300 of the high school students live in families that earn less than $40,000 a year, would have to move or pick up extra work to make rent if it were to increase, struggle to make rent at least a few times a year (with 51 students reporting their families struggle every month), and can trace some of the problems and stresses they experience in their homes back to money issues. 352 of the students planned on looking for a job (in addition to any informal work they already do) to help support their families and 146 students reported sharing their homes with extended family members.

It's a picture of precariousness, the YouthBuild youth agree, but not one they find surprising.

They all come from similar circumstances. And they are familiar with how the challenges those circumstances tend to generate can push youth to engage in risky behaviors, bounce from school to school, and eventually give up on thinking the future might hold much in the way of promise for them.

"Families have been struggling," says Abigail, explaining that many students don't have the luxury of thinking about college. They're too busy trying to help out their families once they graduate (if they continue to live at home, they generally must contribute to rent). And the lack of available steady work in the area means they often have to choose between helping their families and college tuition, bus passes, and books.

And why would you think about college, chimes in Stephanie, if your family is in need of help sooner rather than later? There's not much point to holding down a job while slogging your way through community college, one or two classes at a time. You might as well just start working right away.

It's a frustrating existence for too many, the surveys confirmed, and one that hasn't been well-addressed by the city agencies who are mapping out the future of the community.

Well-intended efforts by Metro and local developers to supply much-needed affordable housing around transit sites do not address the fact that those most in need of stable, viable housing generally do not earn the minimum income required to access those units.

Nor do they address the problem that these projects, roundly rejected in other, better-off communities and now arriving in abundance in Boyle Heights (below), may fail to contribute to the economic vibrancy of the area. Instead, the projects (as designed) may essentially warehouse lower-income residents from other parts of L.A. in the heart of an even poorer community while raising surrounding land values just enough to put pressure on the rents of existing residents and businesses. And they do so without generating much, if anything, in the way of jobs, revenue for existing small businesses, or assistance for local entrepreneurs looking to professionalize their operations and move into the retail spaces at those new sites. In contrast, those retail spaces may sit vacant for months or years until entrepreneurs with enough capital (often from outside the community and/or a franchise) are willing and able to take the risk of moving in.

Or, as in the case of the plans for a retail and fitness center proposed for Mariachi Plaza -- plans Metro was poised to approve without any community engagement whatsoever -- projects can be wholly inaccessible to local entrepreneurs and deeply destructive to the cultural and economic life around important landmarks. Not only would the mariachis and the businesses on the plaza (slated to be torn down) have been displaced, but the other family-owned businesses along the corridor that the mariachis frequent would have suffered a significant drop in revenue, even as the rents for their storefronts continued to rise.

By compiling a snapshot of the key challenges the youth and families of Boyle Heights face and why proposed solutions might fail to resolve them, the YouthBuild students are hoping Metro, the city, and developers will understand why it is so important to engage a wide range of stakeholders in a transparent, participatory process when planning these projects. And they want youth to be seen as an essential partner in that effort.

A mother to two toddlers, Abigail says she is now acutely aware of how much changes in other parts of the community can impact her and her family. She wants to be part of making things better for herself and those around her.

"It's time we [get to] speak up," nods Eric. Too many times, he continues, things that do not help the community are just imposed upon it without any consultation with those that will be affected.

Just because people in the community have been through struggles, Irvin says, it doesn't mean they can't contribute to building a better future. He hopes that people who see him speaking up will understand that, like them, he's been through tough times, too. And that, like him, they will be able to find confidence in their own voices.

"I don't want my daughter to think she doesn't have a voice," agrees Stephanie. "I want her to be inspired. I don't want her to give up. I want to show her that her voice matters."

* * * *

CALO YouthBuild's 2015 Issues Forum is an opportunity for youth to share their knowledge and insights with policy makers and the community at large. Drawing on the results of the student-created surveys, one-on-one engagement with residents, and research compiled under the guidance of Genaro Francisco Ulloa, Canek Pena-Vargas, and other teachers at YouthBuild, students will present on issues related to gentrification, police brutality, and environmental justice, and offer policy suggestions to the panelists and attendees. They invite the community to join in their effort to re-envision the future of Boyle Heights, Thursday, March 19, from 4:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. at CALO YouthBuild, 3626 E. 5th St. (90063). RSVP to the forum here.

*The online survey created by students at YouthBuild was accessible to the high school students via the iPads used in their classrooms. Youth made the presentations and then invited the students to take the surveys.