Where is California's most concentrated bike lane network? Long Beach? Davis? San Francisco? Santa Barbara? San Luis Obispo?

How about Wilmington?

Some readers may be wondering: just where is Wilmington?

Wilmington is a neighborhood in the city of Los Angeles. It is directly inland from the Port of Los Angeles. San Pedro is west of the port, Long Beach is east, and Wilmington is to the north, just inland. Long Beach and San Pedro have waterfronts. Wilmington has more of an industrial truck-front, with no connection to the water.

According to the L.A. Times convenient neighborhood mapping tool, Wilmington takes up 9.1 square miles and, in 2008, had a population of 55,000. Within Wilmington's borders there are port-related industrial areas more-or-less surrounding a central residential district which includes a few commercial corridors. 87 percent of Wilmington residents are Latino; over 60 percent are renters.

Wilmington has some of the worst air quality in Southern California. Ashley Hernandez, Wilmington Youth Organizer for Communities for a Better Environment (CBE,) tells how heavily polluted air becomes harder to breathe on hot summer days; families stay indoors and keep their windows closed. Jesse Marquez of the Coalition for a Safe Environment calls it the "Diesel Death Zone."

The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the largest port complex in the U.S., move goods using diesel-powered ships, trains, and trucks. If the ports themselves were not enough, Wilmington is surrounded by four freeways. Then there is a great deal of oil industry in and around the area, including eight refineries and numerous active oil well sites.

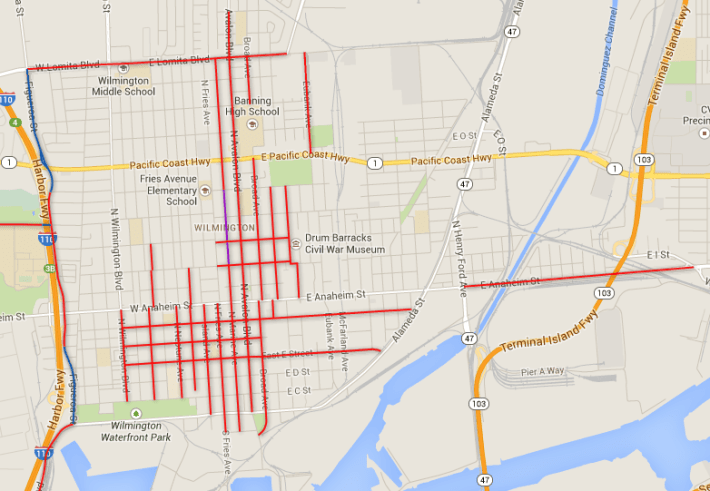

And Wilmington also has a dense network of bike lanes.

Just look at the map above.

I don't know about you, but I have never seen that kind of concentration of bike lanes anywhere in Southern California. It is a difficult thing to confirm, but I asked around, and it appears that this is the most extensive bike lane network in the state.

From LADOT mileage reports, I calculate that Wilmington now has 21.6 miles of bike lanes on about 20 different streets. Nearly all of this is concentrated in that 2-miles-by-2-miles central area. There are 30 fully bike-laned 4-way intersections (places were two bike lane streets intersect.) There have been at least seven road diets: Avalon Boulevard, Broad Avenue, E Street, Figueroa Street, Neptune Avenue, Opp Street, and Wilmington Boulevard. Particularly noteworthy is Avalon, the north-south main drag for the community.

The majority of the bike lane mileage was striped in fiscal years 2013 and 2014. Six additional are miles are planned, including bike lanes on Anaheim Street being studied in the Department of Transportation's (LADOT) "year two" bike lane package.

LADOT District Engineer Crystal Killian (responsible for street configurations in council districts 15 and 8, represented by Councilmembers Joe Buscaino and Bernard Parks, respectively) relates a number of reasons for how these bike lanes came about. According to Killian, Wilmington has "a lot of low-volume, wide streets." Killian continues that many residents "walk and ride a lot" and both the community and Councilmember Buscaino were supportive of "linkages to schools, parks, and employers."

Killian, working with her colleague, LADOT engineer Chris Rider, was able to dovetail bike lanes into other projects already underway. Many wider streets were scheduled for resurfacing, presenting opportunities for re-striping. LADOT had planned to add left-turn lanes as "safety improvements" for Broad Avenue and Neptune Avenue; so they did road diet bike lanes, as listed above. When Caltrans pressed for a second left-turn lane for drivers turning from Figueroa Street onto the northbound 110 Freeway, Killian was able to also remove an excess southbound lane and add bike lanes.

I suspect that a few other factors also contributed to the proliferation of bike lanes.

In June, 2011, Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa issued a directive committing LADOT to implement forty miles of new bikeways each year. Under this mandate, LADOT stepped up bike lane mileage greatly, including striping many streets approved in the bike plan.

DOT also searched the city to find other non-planned low-hanging fruit -- places where bike lanes could be added without impacting car traffic. It is not clear why there are so many of these streets in Wilmington. It is perhaps an artifact of when the streets were initially laid out, their proximity to the harbor, and maybe over-optimistic engineering projections of just how bustling Wilmington would become.

As a relatively low-income community, there are people getting around without a car: many on foot, but also on bike and on transit.

But even with all these new bike lanes, plenty of Wilmington's cyclists ride on the sidewalk, even when a bike lane is available just a few feet away. Similar to the sidewalk cycling in South L.A. and Downtown L.A., these cyclists perceive streets, even those with bike lanes, as more dangerous than sidewalks.

Sidewalk riding occurs along new bike lanes.

It also happens along the few older bike lanes, too.

Cyclists also take the sidewalk where there is no bike lane.

Certainly cyclists are using the new bike lanes, but they're somewhat few and far between, at least on the days I observed.

Many of Wilmington's bike lanes were empty, especially on quieter residential streets, which also had little to no car traffic.

Wilmington residents suggest a number of reasons why cycling has not caught on more widely.

I spoke with cyclist and life-long Wilmington resident Sylvia Arredondo, who is a founder of the Mujeres Unidas collective. Among Mujeres' activities are monthly family-paced group bike rides to promote health and community. Arredondo likes the bike lanes, calling them "super cool," but she also laments that they "go nowhere."

To some extent this is true.

Though the bike lanes are connected within Wilmington, they don't yet make many connections to nearby destinations, including the nearby cities of Long Beach, Carson, and Palos Verdes. Wilmington is surrounded by physical barriers, including freeways, waterfront, waterways, and railroad tracks, so there are only a handful of primary arteries that cross these barriers. While the community's main north-south commercial street (Avalon Boulevard) has bike lanes, its primary east-west commercial streets (Pacific Coast Highway and Anaheim Street) do not. PCH and Anaheim have a lot of car traffic, and feel unwelcoming and unsafe for bicycling or walking. (Anaheim is being studied for future bike lanes, which should help a lot.)

Arredondo also points to Wilmington's history of community violence as contributing to the lack of bicycling and walking, noting parents don't want their kids to be out after dark. Anthony Echeverria, project coordinator for Families in Good Health (FIGH,) echoes this sentiment, saying that "gang activity divides this community" and contributes to a lack of physical activity because it has led to the perception that biking and walking are not safe. This situation is similar to the South L.A. issues my colleague Sahra Sulaiman has described here, here, and here.

In addition to fear of being victimized by gang violence, Wilmington cyclists also fear police.

Arredondo tells stories about the LAPD stopping her on her own street to tell her she shouldn't be biking at night. Again, this is similar to what Sulaiman has written about law enforcement in South L.A., including here.

Nonetheless, both Echeverria and Arredondo say that they, at least anecdotally, have seen some recent increases in bicycling.

In the past, Arredondo states, most Wilmington cyclists were Banning High School students. Now she observes more families -- sometimes with bike trailers, but also including "dads with kids on handlebars."

CBE's Ashley Hernandez expresses a bit more skepticism about the new bike lanes. Though she likes bike lanes and she does "love seeing families" using the lanes, she expressed frustration that they appeared "abruptly."

"One day we woke up and they were there," she says, and they were "not the solution we were looking for."

Hernandez stated that there are major community needs with regard to walkability, green space, recreational spaces, and better bus service on overcrowded local lines.

But, she emphasized, the "real health issues" in Wilmington are cancer, bronchitis, and asthma caused by cumulative pollution impacts from the port, refineries, freeways, and industrial activity mentioned above.

CBE is pressing for Los Angeles to finish implementing its Clean Up Green Up zones which would prevent the development of new sources of pollution and reducing existing ones. Clean Up Green Up is slated for roll-out in Wilmington, Pacoima, and Boyle Heights. See earlier SBLA Boyle Heights Clean Up Green Up coverage here and here.

Echeverria's FIGH programs focus on healthy food and encouraging physical activity, but the physical activity is largely through exercise programs at day care centers. He hopes that Wilmington's new bike lanes "could spark a bike culture," giving Wilmington residents an outlet for daily physical activity. But he also spoke of the pervasive car culture in the community and he observed that if people are walking, it is often only "because their doctor said to" in order to combat an existing health problem.

Bike lanes haven't been a livability, health, or mobility panacea for Wilmington. Clearly there are a few things to be critical of in evaluating Wilmington's bike lanes:

- Large numbers of bike lanes, by themselves, do not necessarily completely solve livability, health and mobility issues. Nor do they generate large numbers of bicyclists, especially in the short run.

- At least some locals are critical of LADOT's process: all changes to roadways should include effective advance notice to the affected community.

- LADOT's product, also has its detractors. L.A.'s most extensive bike network is justifiably described as going nowhere. Many of the lanes are arguably from a well-intentioned overall push to add opportunistic bikeway mileage citywide, as opposed to solving neighborhood-specific problems. As low-hanging fruit bikeway implementation nears completion in neighborhoods, hopefully LADOT can shift to addressing greater connectivity, walkability, complete streets, etc.

SBLA readers know that I am personally very inclined to favor bike lanes, pretty much anywhere. Bike lanes may not be what most of Wilmington asked for, but, at least in my opinion, they are a step in a worthwhile direction. Here are a number of reasons:

- Road diets and bike lanes make Wilmington streets safer. Road diets, especially, have been studied extensively and shown to increase safety for everyone: pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers.

- As streets become safer traffic-wise, residents are likely to walk and bike more. This physical activity leads to better health. More "eyes on the street" contribute to reducing crime. Biking and walking won't solve Wilmington's health and crime problems, but I think they can help nudge them in the right direction.

- Some of Wilmington's very serious air pollution burden stems from car culture. Oil wells, refineries, and freeways exist largely to service car traffic. If Wilmington (and Los Angeles, the U.S., and the world) can become less car-centric, then we will not need to concentrate so many refineries and freeways in Wilmington and communities like it. This culture change may be a slow-moving long-term cycle, and not likely to be comforting to Wilmington residents who are experiencing harmful pollution today.

Wilmington's bike lanes are new. Car-centric patterns of development have held sway there for decades. Oil and port pollution burdens have persisted for the better part of a century.

Community leaders, including Arredondo, Hernandez, Echeverria, and Marquez, are seeing some fruits in their struggles for the health and the quality of life for Wilmington families. There is a long way to go, but I hope community victories will continue, and that residents can enjoy their successes, potentially while walking and bicycling on Wilmington streets.

If you're interested in exploring Wilmington and its bike lanes, you might enjoy an upcoming all-ages community group bike ride hosted by Mujeres Unidas, C.I.C.L.E., and others. The Harbor Halloween-themed ride is slated to take place on Saturday, October 25th. Details are still being finalized, but more information is available here.