"If you drink and drive and kill someone again, [this time] it will carry a charge of murder with a minimum sentence of 15 years," the judge told 21-year-old Wendy Villegas at her sentencing hearing. "Do you understand?"*

Her words had been meant to admonish Villegas -- to convey the idea that slamming into a group of cyclists, killing Luis "Andy" Garcia and leaving Mario Lopez and Ulises Melgar for dead, was a very serious offense.

Unfortunately, the judge's warning that the book would be thrown at her next time only served to underscore the fact that our laws do not yet take drunk driving or hit-and-runs seriously enough.

Fire a gun into a crowd and injure four people at a party at USC, and you'll get forty years to life.** Get behind the wheel, and you apparently have to kill a second time before the death you cause is legally classifiable as a homicide.

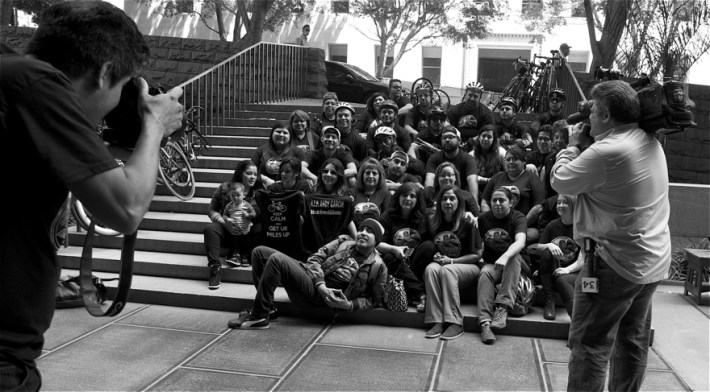

From where I and 40 other members of Garcia's family and friends sat, staring at the back of Villegas' head, it was hard to tell if the judge's words -- or anything else, for that matter -- made an impression on her.

She never met anyone's gaze as she walked in and out of the sentencing hearing, never turned to look at anyone as she sat facing the judge, never appeared to show any emotion, and never uttered a word, other than to answer the judge's direct yes-or-no questions.

It drove Garcia's friends and family crazy.

Cynthia Garcia, Andy's cousin, was the first to say so in her impact statement.

Shaking as she addressed Villegas' stoic back, Garcia railed at her for not having enough respect for the family to accept responsibility for what she had done.

"You can't say sorry?!...I hope [it] haunts you! I hope it keeps you up late at night!" she sobbed. "What you took away from us, we won't [be able to] get back!"

An aunt, Yvette Holguin, described how Andy had fallen in love with the city shortly after moving here, and how he had posted photos from the bike ride he and his friends had gone on that night in September, "not knowing he had his hours counted."

She recounted having screamed upon hearing that Andy had died so horribly and cried as she recalled the pain of having a closed casket at the memorial service.

At first, she had asked herself why Andy had felt he needed to ride that night, she said.

Then it dawned on her, she continued, that "the choices he made were not illegal."

It was Villegas who had had too much to drink that night and who had made the illegal choice to get behind the wheel. It was Villegas who had made the illegal choice to leave the scene. Yet, it was Andy who paid the price while Villegas continued to appear unmoved by what she had done.

Perhaps Villegas realized, Holguin mused bitterly, that "hit-and-run penalties are a joke."

Another of Andy's aunts said that not one day had gone by that they hadn't thought about him.

Knowing he had been left to die in the street had shattered them, she said. But the pain was made infinitely worse by Villegas' complaints to the court about having to coordinate her ankle monitor with her shoes and the financial burden taking a life had placed upon her.

She realized that Villegas' lawyers had likely advised her to show no emotion and to avoid addressing the family, she said, but she couldn't help but feel "it was bad advice."

"No one should have to live through this... especially with no [apology from you]," she said through tears. "There's nothing wrong with human decency."

The statements of Akira Peña, who had dated Garcia for 8 years, were perhaps the most heart-breaking. The couple had temporarily split after moving to L.A., but had finally agreed to get back together in September, telling each other they believed they were soul mates.

"A few hours later," she wept, "[Villegas] took his life!"

"That was the love of my life!...You took that away from us!" she wailed, her tiny frame shaking. "We were going to get married! We were going to have kids!"

By the time she finished speaking, the entire courtroom was in tears. If Villegas was moved, however, she gave no indication.

Even the judge appeared exasperated by Villegas' demeanor as she read off the sentence of 3 years and 8 months to be served in state prison.

"I always look for silver linings," the judge began quietly, referring to her desire to see something good come out of the terrible incidents that regularly come under her jurisdiction.

Appearing genuinely troubled, she confessed that, in this case, she hadn't been able to find any.

Recognizing it wasn't necessarily up to her to come up with the answer, the judge indicated the time Villegas would serve might give her the space to reflect on what she had done.

"I hope," she said, addressing Villegas directly, "you can figure out what that [silver lining] is."

+ + +

*Bizarre as the judge's statement sounds, she was describing the current unfortunate state of our laws with regard to how hit-and-runs are classified, not her personal feeling about what happened. The attorneys had decided amongst themselves--without consulting the other victims or Garcia's family--to offer a plea deal that allowed for a more lenient sentence instead of the maximum of 15 years she could have served. For more on that, please see here.

**Sentencing in both of these cases seems woefully arbitrary. And in most such cases, for that matter. In the case of the hit-and-run that killed USC student Adrianna Bachan (where another student was left for dead), both the driver AND her husband, who pulled the injured student off the windshield, were sentenced to 8 and 7 years, respectively.