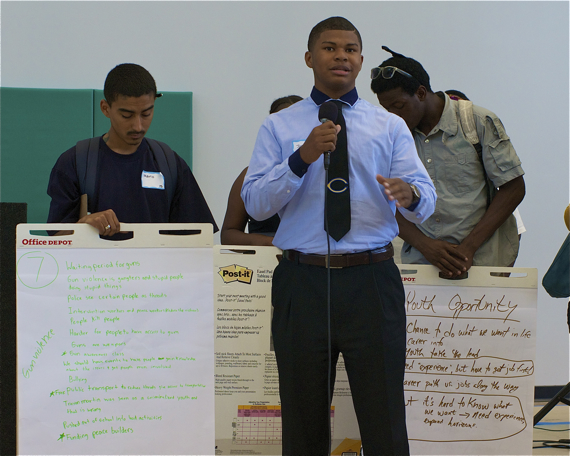

When asked by his group's facilitator whether he believed the youth in South L.A. had opportunities -- opportunities to grow, succeed, try new things, advance their education, you name it -- one young man said he was convinced that the answer was a resounding "no."

It wasn't just that opportunities weren't there, the dapper teen from Crenshaw High School (below) told the youth, facilitators, and representatives from the mayor's office who had gathered to hear South L.A. youth perspectives on how to address the problem of gun violence in their communities. It was that the environment he was raised in did not prepare youth to make the most of the few opportunities that were available to them.

Speaking of a youth leadership conference he had attended in Sacramento, he said he was struck by how different he and his South L.A. peers were in their approach to thinking about their futures from other youth.

The other students -- the majority of whom were from well-to-do communities around California -- had all traveled so much and were so open-minded, he said, that they "[were] not aspiring to work anywhere. They were aspiring to innovate."

He'd never seen anything like it.

"They were like TV people -- I didn't know they existed."

South L.A. youth needed to have some of those same opportunities to travel, to see new things and ways of life, and to expand their horizons, he concluded. They also needed to believe that the sky was the limit for them if there was any hope of things changing for the community.

It was, perhaps, not the response that the mayor's team expected to hear from participants when they decided to put together a "Youth-Led Town Hall" to address the issues underlying the frustrations expressed by the community in the wake of the verdict in the Trayvon Martin case. But it was actually par for the course among this group of activists.

While there was some discussion of gun violence and gun control, the majority of the 100-plus youth present believed that mitigating such violence in their communities required tangible and sustained investments in dealing with the root causes of violence and investing in youth, education, and intervention work.

"I don't think gun violence is the problem," said a young man summarizing his group's ideas. "I think anger is the problem."

In his experience, happy people didn't go around shooting each other.

And that unhappiness, he and others argued, stemmed from the absence of purpose in people's lives due to a combination of a lack of job and educational opportunities, of basic needs not being met, of traumatic experiences that left people feeling vulnerable, of the criminalization of poor youth of color, and of the inability of people of color to rely on law enforcement for help.

The poor relationship with law enforcement was a particularly important issue for many of the youth.

Current policing practices actually helped keep communities violent, youth leader Tanness Walker suggested, synthesizing the comments made by others in the group she was facilitating.

A young woman in the group named Brittany had talked about being robbed by a man who raised his shirt to let her know he had a gun tucked in his waistband. She called the police, she said, but it took so long for them to show up that the delay made it dangerous for her to give them too much information. Because he was now long gone from the scene, apprehending him would take some time, if it happened at all. Police poking around based on her information would actually endanger her or her family, as the perpetrator -- someone who lived in her community -- would know that she had spoken up.

Guarding her family's safety, in other words, meant keeping quiet and allowing a man armed with a gun to remain at large on the streets of her neighborhood.

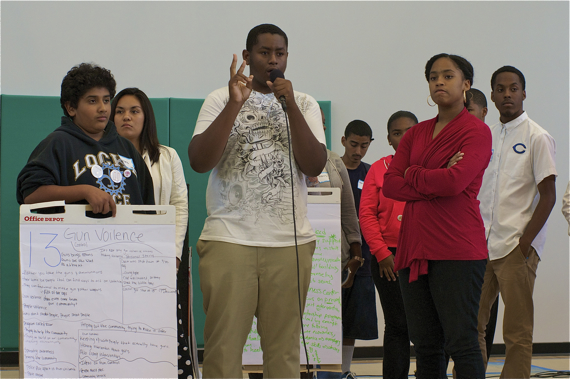

Another young man, Jason Law (below), decided his solution was to arm himself with a knife.

He didn't want to carry it, he said.

He had no intentions of committing any crime, violent or otherwise.

But, he felt he needed to have it in the event the gang-bangers who had first threatened him approached him again so he could say, "Hey, back up, one, two, three, four, five of you..."

In the end, it was he who ended up being hauled into the police station, not his tormentors.

It was just for possession -- he never used the knife on anyone, but police found it on him when they stopped and frisked him one day.

The whole process made him feel like he was an animal, he said.

They didn't care that he was a good kid and didn't bother to ask him about why he felt he needed the knife. There was no attempt at mentoring or any effort to build any kind of relationship or trust with him in any way. Instead, he described the humiliating sensation of officers looking as if they were pleased to get one more "thug" up off the street. It didn't help, he said, that he could hear other officers at the station disparaging youth amongst themselves.

I wondered what the police milling around the back of the gymnasium or occasionally eavesdropping in on some of the groups were making of these discussions. It's one thing when I write about it -- it's another thing entirely to hear kids in the area say to your face that their cousin was shot, that they fear for their family's safety, that they get banged on on their way to school, or that they feel like criminals because they are constantly getting stopped and frisked by police while the real trouble-makers continue to make their lives so fraught.

The youth were dismayed that Mayor Eric Garcetti and City Attorney Mike Feuer had not been able to stay to listen to the youth in person. They had opened the forum with speeches and pledges to make Los Angeles a safer and healthier place for youth of color and expressed a desire to hear the youths' concerns and potential solutions, but left soon after because Garcetti had to meet President Obama at the airport.

Although Garcetti had pulled out his phone and recorded the youth saying in unison that they wanted to see more intervention work done in their communities, the soundbite didn't really capture what that phrase meant to them.

Beyond the policing issues mentioned above and obvious gang intervention work, "interventions," to them, meant more investment in youth like themselves -- the kids that worked hard and stayed out of trouble. And they wanted earlier interventions in schools so that more kids would be encouraged to work hard and aim high instead of seeing gang membership as their only option. More teachers in schools, more counseling and help for those suffering from mental health issues, more efforts to channel young people's energy through artistic fora, more career and entrepreneurial training opportunities, more jobs and internships for youth, and more opportunities for youth who started down the wrong path to find their way back.

One wanted a youth mayor -- someone that would be in charge of listening to and addressing youth needs.

Another asked for more positive attention on the community.

"Where is the media?" she demanded, complaining that they would only care about what she had to say if she shot someone.

As the summit drew to a close, the staff of the mayor's office promised to take the messages they had heard today back to Garcetti and to keep the dialogue alive.

They certainly had a lot of material to work with. Any one of the policies the youth were arguing for, if implemented as they envisioned, could have a lasting and significant impact on the livability of South L.A.

But, none of these complaints or proposed solutions were particularly new.

And that's what can be frustrating about these feel-good forums sometimes: there's a lot of excited talk but no clear understanding of how any of it will materialize into action at some point. A concern that didn't escape Alezaihvia Melendez, a soft-spoken and sweet young woman with big dreams.

Describing an effort in which she and other youth activists "took over" Martin Luther King, Jr. park and took it back, at least temporarily, from the gang-bangers hanging out there, she urged others to do something similar in their communities instead of waiting for aid that might never come.

"Youth have the power," she said. "If we use it right, there's no telling what we can do."