"What you got on you?" the 15 year-old girl says the cops pulled up alongside her asked as she walked along Vermont one night.

Bundled up in her boyfriend’s jacket to stave off the chilly air, she didn't realize that they were actually talking to her until she heard one grumble, "Fucking Mexican!" and repeat the question.

Now she found herself both amused and pissed -- not only were they messing with her, she's Salvadoran.

"I was like, ‘Dayum, for real??’" she laughed as she recounted the incident to me over a plate of fries at a little restaurant not too far from where she had been stopped.

She was just going to the market, she told them. She didn't have anything on her.

"Well, you just look [like you're] bad," she says the cops told her before pulling away.

I cradled my head in my hands. I had spent the last month and a half moving up and down the streets around USC, speaking with lower-income black and brown male youth (aged 14 to 25) about the encounters they have had with officers from the LAPD and USC’s Department of Public Safety (DPS). Every single one of the approximately 50 youth I had randomly approached for an interview told me multiple stories about getting harassed, insulted, stopped, and sometimes even frisked and handcuffed by both DPS and the LAPD.

But I hadn’t expected to hear a story from her.

She’s tiny – maybe 4’10” on a good day – and she’s been working hard to stay out of trouble. In fact, she had recently moved up to the USC area to get away from the craziness and drama of the streets in Watts, where she had lived for the last several years. There, she was stressed from having to constantly watch her back. Her new neighborhood seemed so peaceful in contrast.

"You realize there's a Harpys clique just up the street, right?" I laughed, pointing over my shoulder.

"Huh?"

She had never even heard of them. The only trouble she had had was with the cops. But it didn’t faze her, she said, waving me off dismissively. That kind of thing is normal.

___________

Rites of Passage in the ‘Hood

"Normal."

"Happens all the time."

"It’s like a rite of passage."

All across Los Angeles, these are ways that a lot of youth of color from lower-income communities describe being stopped, questioned, searched, or, on occasion, falsely accused of misdoing and arrested or even brutalized by the police. Such incidents are so prevalent, in fact, that I’ve had to postpone meeting up with people that wanted to tell me their stories about enduring harassment in order to finish this article. The list of friends, acquaintances, and random people I’ve encountered that regularly experience this kind of discrimination is actually that long.

Most strikingly, although all describe hating how disempowering, humiliating, and even traumatic it can be, and that it feels like the police prefer sweating them to keeping them safe, they tend not to think of getting stopped as anything out of the ordinary.

It sucks, they tell me, but it comes with growing up in the ‘hood.

Until recently, many of the residents – young and old -- in the neighborhoods around USC might have felt no differently. They were used to being scrutinized by both the LAPD and DPS, monitored by some of the now 72 cameras USC has set up on and around campus (watched 20 hours a day by LAPD and round the clock by USC), and observed by the more than 30 security ambassadors positioned on campus and throughout adjacent neighborhoods.

“We know [LAPD and DPS] are going to slow down [their cars] when they see a group of us standing out here like this,” an older black gentleman said of himself and his friends as they chatted in front of his home under the watchful gaze of cameras posted up on Normandie Ave.

“They always do.”

His friends nodded solemnly.

Since the implementation of new security measures around USC following two shootings in the area last year, however, things have apparently become more intense than “normal” for some. In particular, the stepping up of DPS patrols on and around campus combined with the arrival of 30 officers to the Southwest Division to conduct high visibility patrols and “more frequent parole checks on local gang members” (the $750,000 worth of personnel costs which were paid for by USC) have put everybody on notice.

Neighbors (and, most recently USC students of color, apparently) really began to feel the shift in tone with the beginning of the fall semester, when the new measures went into full effect.

The reason? Despite DPS’ use of "video patrol" techniques and the LAPD’s use of cutting-edge computer-generated models to aid in predictive policing, the methodologies behind the identification of suspicious behavior or candidates for "parole checks" appear decidedly unsophisticated.

And aggressive.

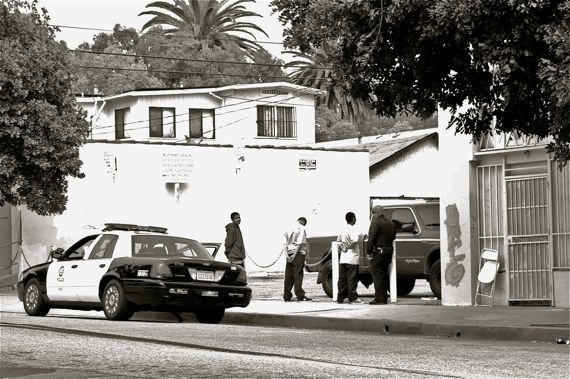

Black and Latino youth report that officers from both the LAPD and DPS regularly pull up alongside them and verbally accost them with a barrage of questions.

Where are you going?

What are you doing here?

Are you on parole?

What you got on you?

Are you on probation?

What are you doing here?

Oh, I'm sorry. Did I repeat that last one?

It's the one kids tell me they are often asked multiple times during a stop.

It's also the one that frustrates youth like Fidel Delgado the most.

How many he times does he have to tell an officer what he is doing? Why does he need to justify being in a neighborhood he has lived in nearly his entire life?

Doesn't he have a right to be there?

Apparently not, as he has had to explain his presence while standing on a corner waiting for a friend, walking down the street, and just hanging out in a friend’s yard.

Worse still, Delgado says, while working at a coffee shop across the street from USC, he found himself serving coffee to at least one of the officers that harassed him.

They must have known who he was, he thinks. Yet, they did it anyways.

Other kids report being questioned on their way to and from school. A 15 year-old Latino youth said he’s been stopped while walking to West Adams Prep (at Washington and Vermont) in the morning and asked if he had marijuana on him.

“You look like a stoner,” he says an LAPD officer told him.

Still others – especially those that have never been in trouble – take issue with being stopped and hounded about their parole status or having DPS officers call in the LAPD to run warrant checks on them. Since none of the youth I interviewed were on parole, none of them could tell me what happened when a parolee was found. They did say, however, that the LAPD is seemingly so desperate to find parolees that they have been known to stop by gatherings at private homes just to ask whomever is standing outside if anyone there is on parole or probation.

Maybe they are worried about seeing so many Latinos together, Delgado had half-suggested/half-joked when he first told me it had happened to him and people he knew. It didn’t make much sense to him as a policing strategy unless the objective was to let people know they were being watched.

“We want better relationships with the cops,” a man in his mid-twenties who lived off Portland St. said, echoing comments I had heard from several interviewees. “But they have to stop seeing us all as criminals first.”

He was fine with officers stopping people from doing things they shouldn’t be doing, like drinking or smoking up in the street. There was a house in the area that was a known gathering spot for that kind of thing, he said.

But why, he wanted to know, do they have to keep questioning all the youth or telling them to stop throwing a football around on a quiet side street? Officers seemed to take pleasure in finding ways to keep kids from being able to be out and about in their own neighborhood, he felt, while ignoring when kids along fraternity row were doing the same kinds of things and worse. It didn’t seem fair.

And stop with the arbitrary searches, pleaded several interviewees, each of whom seemed to have been more than a little traumatized by their experiences.

“They touched my balls! They touched my balls!” screeched a 14 year-old African American skateboarder hysterically, one of four interviewees who mentioned getting stopped by the “Jump Out Boys” from the LAPD. (note: the Jump Out Boys were a gang within the Sheriff's, not the LAPD. My understanding from the interviewees was that the label was more about officers "jumping" out of their cars to intimidate them and/or conduct a very physical stop with no provocation.)

“I was just walking by myself! I wasn’t doing anything!” he said, when they piled out of their car, grabbed him and searched him as he walked along 35th St.

“And, they touched my fucking balls!” he reiterated, adjusting his pants. “For no fucking reason!”

A 17-year-old Latino skateboarder said he got stopped near campus because police said they were looking for a bike thief.

“I was like, ‘OK, if you need to do your job, I understand’…but then I had to put my hands out and spread my legs and [the officer] touched my balls…” he shuddered, laughed nervously, and looked down at the ground.

It’s not like he had a bike hidden up in there.

Sounding slightly embarrassed and still staring at his feet, he asked, “I mean, was that really necessary?”

___________

For Some, DPS Is Even Worse

Unhappy as the youth were with their treatment at the hands of the LAPD, it was nothing compared to the disdain they reserved for USC’s Public Safety officers.

Where the LAPD seemed to represent a known -- if not well-liked -- quantity that had a specific job to do, DPS appeared to be considered another animal altogether.

After an initial eye roll of disgust, youth would often recount some overzealous interaction with DPS officers that was reminiscent of a terrible, low-budget drama where tough-guy cops shoot their way in to places and shout angry commands at evil mob bosses to put their weapons down and their hands up or face the consequences.

Given that the youth are not mob bosses, or even petty criminals, many feel that the officers are harassing them just for the hell of it.

Two 15-year-old African Americans who were leaving campus, for example, said they didn’t understand why DPS officers would do things like chase them off a practice field when the coach had been fine with them being there all afternoon.

One shrugged and said they probably needed to get going anyways. It was nearly 6 p.m. and, in their experience, that was about the time that DPS really started cracking down on people they thought shouldn’t be there.

The days they had stuck around too late in the afternoon, both said, they would sometimes be hustled off campus only to be stopped and questioned again a few blocks away by another set of DPS officers (or sometimes LAPD).

When DPS officers make stops like that, kids report they are often not informed about why they are being held up and made to wait.

“He finally let me go,” a 17-year-old said of an officer that stopped him on campus and held him for several minutes while going back and forth with someone on a walkie-talkie.

“But, I don’t know why he stopped me in the first place – [the officer] never told me.”

In other cases, officers seem to have no real purpose for engaging kids beyond intimidation.

On a beautiful Saturday afternoon, a group of 5 gangly Latino and African American boys between the ages of 13 and 16 recounted how a DPS officer had pulled up in front of the house where they were hanging out earlier and demanded to know what they were doing there.

After telling the officer that one of them lived there, one said, the conversation somehow escalated to the point that the officer told them, "If the mailman can come up into your house to deliver the mail, then I can come that far up into your house."

"Wait, what?" I asked.

"Yeah," another boy confirmed, explaining how the mailboxes for all the residents were just inside the front door and the DPS officer said that meant he could go that far into the house, too.

"We could film it and send you the video next time it happens!" one of the boys suggested eagerly.

"It happens that often, huh?" I asked.

"Yeah," he and his friends nodded.

People needed to know how out of hand things were getting, they said.

It is way out of hand, agreed a 16-year-old who lived northwest of campus.

While he had been hanging out on the corner with a friend, he recounted, a DPS officer had come by and told them they couldn't be there. When the boys responded they lived right there, things apparently escalated. The officer asked if they were getting smart with him, handcuffed them to the neighbor's fence, and called LAPD to come do a check.

"I live on this street!" the youth told me angrily, throwing his arms wide.

They have always just taken things too far, Fidel Delgado concluded when I spoke to him recently about the stories I had heard from other interviewees. Then, he offered his own story of an encounter he and his friends had had with DPS before the new security crackdown.

During a stop by the LAPD near Mount Saint Mary's, he said, the officers ran their names, searched them, and found a weed pipe on one of his friends. Being that it was all they had on them and they were otherwise causing no trouble, the officers said they would let them go.

"They were being pretty nice about it," said Delgado.

Just then a DPS vehicle pulled up.

“Do you need any help?” they asked the LAPD officers.

Instead of accepting that the youths were not causing trouble, DPS forced the issue, handcuffing all of the boys and loudly commanding they not move their hands unless they wanted to get knocked out or dropped on the ground.

It didn’t make sense to Delgado – the LAPD hadn't had a problem with just letting them go about their business. Yet, they’d somehow ended up handcuffed, threatened, and hit with a ticket for having the pipe. No weed -- just the pipe.

The whole thing sucked, Delgado said, because "we couldn't move, but the handcuffs were really tight."

Even the LAPD officers felt bad, he said, offering he and his friends a half-hearted apology as they handed them the citation.

____________

Things Suck. We Get It. Now What?

What do you want us to do about this? What changes would you like to see?

The questions had come from Sgt. II Jonathan Pinto of the Southwest Division of the LAPD.

He, Capt. III Paul Snell (also of Southwest), Chief John Thomas (DPS), and Capt. David Carlisle (DPS) had agreed to sit down with me and hear the stories that I had gathered from the community. They had listened patiently as I listed off complaint after complaint about both DPS and the LAPD for over an hour, interrupting only to ask for clarifications and any specific information I could offer about particular incidents.

They appeared troubled by what they heard.

Snell and Thomas – both of whom are African American – said that they were familiar with stories like these, having grown up in the area and been subjected to similar practices. Both expressed being dismayed and disheartened to hear those practices appeared to be alive and well. This wasn’t what they were about or what they wanted from their officers, they, Pinto, and Carlisle all reiterated, citing the number of youth programs and community outreach efforts each force has as being more reflective of the relationships they have worked to build with residents.

But they also had no way to answer any of the specific claims because they had no independent way to verify them.

Every time an officer gets out of the car for a stop, Pinto told me, it is recorded with video and audio. Going through a number of the records from recent stops prior to the meeting, he said, he was unable to find evidence that juveniles were being stopped with the frequency the youth are claiming.

According to the youth, however, much of the harassment they experience doesn’t come in the form of a formal stop. The officers engage them from their patrol cars or even in passing on a sidewalk while heading back to their vehicles after taking a break at a café or the 7-11 on Figueroa. In those cases, the recording equipment is never activated and no paperwork is filed.

There are mechanisms in place if the youth want to complain, Snell offered.

Both he and Pinto said a youth could always ask for a supervisor if they were unhappy with how they were treated or file a formal complaint after the fact.

Those mechanisms are valuable. But there are several very good reasons why it is unfair to put the onus on kids to speak up to an officer in a situation where they are at such a clear disadvantage.

- “Who would believe me?”

With regard to filing reports, those youth that do consider it are often sure no one will believe them. In some cases, they are too humiliated or traumatized by their experience to want to have to relive it all again when they are convinced their claims will be rejected anyways.

Their concerns are understandable. Even when I’ve raised the issue of profiling before, a significant number of people have been quick to say that they can’t believe it is as bad as I suggest. Some allege that perhaps I haven’t gathered enough information, spoken to the right people, or trusted that the police had a good reason to stop the youth.

But for the youth, it’s personal. And it’s painful.

The skateboarder who experienced the invasive search, for example, said it is incredibly frustrating that his white friends at the school he is bused to refuse to believe he gets stopped all the time. He has no way to prove it to them, since it never happens when they are together. His insistence that it happens makes him look like a liar. Or, like he might be a shadier character than he lets on.

Another youth and I were told by two LAPD officers that USC and the LAPD were pressuring them to deliberately profile anyone and everyone that was not affiliated with USC.

Despite what USC, the LAPD, and DPS have all said with regard to that being categorically untrue, the fact that many of those affected in the community perceive profiling to be accepted practice means they view pursuing complaints to be little more than an exercise in futility. It makes perfect sense, therefore, that few teens would step forward to voice their concerns.

- Speaking up is hard to do.

With regard to speaking up in the moment of an interaction with an officer, the odds appear stacked against the youth here, too.

Both parties are acutely aware that there is a significant power differential between them. And, if officers are coming at them aggressively, as the youth claim, it immediately puts the youth in the position of having to defend or justify themselves. For youth afraid of being labeled as troublemakers or fearing officers will find some excuse to accuse them of violating the terms of their parole or probation, a basic stop can quickly become a highly anxiety-inducing experience.

Even if a teen managed to avoid freaking out long enough to engage an officer about the legality of a stop, most are still easily shut down with one simple phrase.

“I can be nice or I can be a dick.”

It is a line youth say is commonly used by all of the forces to get them to comply with the officers’ demands.

An officer with the Sheriff’s Dept. in East L.A. used it on Fidel Delgado and a friend of his when they protested there was no probable cause for the officers to pull them out of their car and search them. They had been sitting in the vehicle, eating and killing time before their class at the community college when the officers happened upon them.

By essentially telling Delgado and his friend that they had to consent to the searches of their backpacks and the car to avoid something worse, the officers made it clear that they weren’t going to take ‘no’ for an answer.

It worked.

Worried they might miss their class and overwhelmed by the barrage of questions flying at them, the young men gave in and consented to the searches.

In the worst case scenario, protesting a stop can result in a false arrest, as it did for a young friend of mine in Watts.

Hanging out outside his home, shirtless and in sandals at 9 a.m., officers from the LAPD pulled up, threw him against the hood of the car, and called for back-up when he started yelling for witnesses that he was being manhandled with no probable cause.

When he resisted being put in the back seat of the car by bracing himself against the door (because he still hadn’t been told why he had been stopped), the officer claimed the youth had kicked him and arrested him. When the youth asked to speak to a supervisor at the station, the supervisor said he would only speak to him in front of the arresting officer.

Too traumatized and angry to get words out, he broke down while being processed and was unable to make a written statement. At that point, he still didn’t know why the officers had approached him in the first place. They never told him directly – he only heard that he was picked up on suspicion of burglary when his cousin came in to visit him. He apparently had had the misfortune of being the first African American male wearing blue shorts that the officers had spotted that day. So, he sat in jail, missing classes from a training course tied to a job opportunity, only to be released five days later because the officer had never filed a report -- there were never any charges against him.

“Did you tell them your father had been a police officer?” I asked.

No, he said. He wasn’t sure that it would have made any difference. And, he was in such shock from how the arrest had gone down that he had had trouble figuring out what the right things to say were. When they wouldn’t let him talk to the supervisor, he said, he kind of gave up hope that they would listen to him anyways.

“What about filing a complaint…?”

People had encouraged him to do that, he said. But he preferred putting it behind him and staying far away from law enforcement.

One major bout of humiliation was enough. He didn’t want to have to think about it anymore.

- You better exercise that right to remain silent.

The fact that many of the stops I’ve catalogued – formal and informal – seem not to be based in any kind of probable cause makes it even more difficult for youth to speak up.

“Are you getting smart with me?” is a typical retort youth complain of hearing when questioning an officer.

From there, the door is open for a simple stop to escalate to something much more serious. The less justifiable the stop, the more aggressive the arbitrary assertion of authority seems to be, especially if the person being stopped decides to push the issue. Even Chief Thomas was able to recount moments from his own youth in which he realized it was clear that saying the wrong thing to an officer could have harsh consequences, as it had for friends of his at the time. It didn’t matter if he was in the right.

“Biased policing continues to be one of the key challenges that we face,” Police Commission President John Mack said in 2010, when the LAPD announced they would be installing cameras in 300 South L.A. cars to address racial profiling concerns.

He may have been referring to a 2008 study of 700,000 of the LAPD’s own 2003-04 data files which found that, after controlling for violent and property crime rates in neighborhoods and other variables, not only were African Americans and Latinos “over-stopped, over-frisked, over-searched, and over-arrested,” their “harsher treatment by police…[didn’t] appear to be justified by any legitimate law enforcement concerns.”

“Although stopped blacks were 127% more likely to be frisked than stopped whites,” wrote study author and Yale Law Professor Ian Ayres, “they were 42.3% less likely to be found with a weapon after they were frisked, 25% less likely to be found with drugs and 33% less likely to be found with other contraband” (emphasis mine). Researchers found similar patterns for Latinos, who were 43% more likely to be frisked than stopped whites.

Healing its relationship with those communities is a slow process, according to Commander Richard Webb, head of Internal Affairs.

The wider use of cameras and last year’s shift to a focus on “constitutional policing” while reviewing complaints (i.e. assessing the legitimacy of a stop, the officers’ actions, and whether people were searched, instead of just looking at questions of race) could help the LAPD ferret out deeper problems. But the true test of system, Webb suggested last October, will be the willingness of command staff to take complaints of profiling seriously and discipline officers based on the results of investigations. Their continued reluctance to do so has meant that Internal Affairs still remains in charge of the investigation of complaints.

That doesn’t mean the system can’t work -- an officer in West L.A. was found guilty of profiling last year. He was discovered to have gone as far as to “misidentify” Latinos as whites on some of his reports, presumably to conceal his propensity for the practice.

Still, the system relies on people coming forward make complaints for investigations to be set in motion, and that is a very tough sell in many communities.

__________

Where USC Fits In

While guest lecturing at USC recently, I was asked to make an argument for why students and their parents should care about racial profiling. How would I counter the claim that students are paying a lot of money to be at the school and they have a right to expect to be safe?

Beyond the obvious - e.g. human rights, concerns about equal treatment of all people, and fears about incidents like the one that killed Trayvon Martin - it is important to understand that the stops have deeply detrimental effects on the youth that are targeted and on the community as a whole.

These youth are not the perpetrators of crimes against USC students. The shooting on campus was perpetrated by a gang member from Inglewood against another gang member whose territory is south of Vernon Ave.; the guys behind the shooting of the grad students appear to have been linked to a gang three miles west of campus. Those bent on robbing USC students keep track of the school's calendar. Moving-in days, spring breaks, holidays, festivals, and the like bring in opportunists from as far off as Pacoima.

That is not to say that there aren't problems in the neighborhood. Southwest is a busy division with a number of challenges. But there was only one youth I spoke with that had a criminal record, and it wasn't for anything related to USC. Time spent harassing these kids is time not spent dealing with those that pose an actual threat to the area.

But, observers of a stop have no way of knowing that.

Instead, they tend to assume that the youth must have done something to merit the attention and that the police are just doing their job. Some have even described being grateful to see that the police are actively working to keep them safe from potential danger. Even if there was no cause for the stop, the stop itself has served to confirm the stereotype that the students need to be wary of certain youth of color and, by extension, the wider community. Add to this the sheer frequency with which DPS and LAPD officers appear to be questioning youth, and it becomes clear how easy it is for policing techniques to reinforce divisions between communities.

Because of these divisions, USC students may lose out on an opportunity to be more integrated in, learn from, and contribute to the vibrant urban community that surrounds them. While many do participate in one or more of USC’s many programs that give back to the community, it still isn’t always easy for students to see the connection between the people they serve through those programs and the people they live next door to. Other students are less willing to give neighbors the benefit of the doubt at all, convinced that the need for such an intense police presence is confirmation that they live in “the ghetto” and that the neighborhood “sucks” - commonly heard student complaints.

The segregation can be even more detrimental for the self-esteem of the youth in the area. Not only are they made aware that they are treated very differently by law enforcement simply because of who they are, they can see how it affects the way students view them. Many told me they were accustomed to being ignored, feared, or given dirty looks while on or near campus. While many like the idea of going to a college like USC, the sense that they are not always a welcome presence in student-heavy areas of their own neighborhoods makes them unsure they would fit into such an environment, even if they had the grades to get there.

In darker moments, a few have confessed, they get discouraged by the idea that, regardless of how hard they work or what they accomplish, they are still going to be viewed with suspicion.

Meanwhile, these youth are just as at risk, if not more, for getting jacked, roughed up, or recruited by a gang as they go back and forth to school or try to hang out with friends. Fearing law enforcement would not protect from retaliation by the perpetrator -- often someone known to them -- they rarely report the crimes.

That lack of security is often behind the decision of youth to band together in crews (for more about crews, see here). They want protection and the reassurance that someone will always have their back if something should happen to them. And while many of those kids get more caught up in beefing it with each other than anything else, the crews can also send kids down a path that is tough to break away from.

Which means that making neighborhood youth feel more secure -- protecting them from harm instead of criminalizing them -- makes everybody more secure in the long run.

We all want to be safe. That's natural. And, there are genuine issues of concern that pose safety threats in the area. But true security is about more than fences, gates, and visible patrols. It is about inclusion, communication, integration, relationships, and respect. When the desire of some to be safe comes at such a high cost to others, everybody loses and everybody is worse off for it.

It really is that simple.

********

See our follow-up story here. It looks at the uproar over the unequal treatment black USC students received after a party was shut down for being too noisy.