Whenever I travel in and out of LAX, I do my best to Metro my way there.

It requires a forty-minute walk, three trains, and an airport shuttle ride for me to go one way. But, it's cheap and, remarkably, it all goes down in less than two hours. And, it is never dull.

For one, I get to watch new arrivals stumble their way through the TAP machine at Aviation.

This time, it was a lawyer from Toronto who hung back from the crowd that lunged for the single TAP machine near the elevator, where we were dropped off.

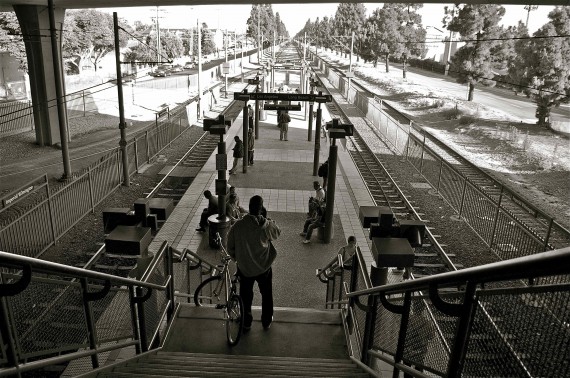

I hadn't actually taken a look at this ticket-vending machine (TVM) before because I always reach the platform via the stairs at the east end of the station, where the shuttles usually stop. This TVM had none of the semi-helpful maps and informational posters (if you are an English speaker) present by the base of the stairs.

The lawyer hoped that watching other people go through the motions, he'd figure it out.

He didn't.

He reassured me later that he would have gotten the hang of it with a little more time. He rides public transit a lot, he said.

Having watched him try to navigate the system, I wasn't so sure.

He was going to have to take three trains (Green, Blue, Purple) and maybe a bus in order to get himself close to LACMA, and didn't realize that meant that he would need to pay several separate fares. That part wasn't in the directions his friend had sent him.

He stared at the screen and looked back at the directions on his phone. Buy a card or add a fare? He looked at me.

It dawned on me that while Metro has made it somewhat easier for frequent riders to navigate the system with recent changes to the menus, those shortcuts may make it more challenging for newbies.

As found during a recent Metro-run focus group, people don't look at the information on or around the machine itself, they focus on the screen and the menus, assuming those will provide answers at some point. It would therefore make sense if the first screen greeting users also had a static list of fun, helpful tips such as "Each Train Requires a Separate Fare!" "ALWAYS Touch Your Card to the Blue TAP Circles at the Turnstiles or Validators Before Boarding!" or "Seniors Get Discounts!" It would also help if the "help" option was, instead, an interactive "information" option that took you to a list of things you could get more specific information about, such as transfers, fares, maps, passes, basic how-to stuff, timetables, and so forth (instead of the achingly slow and not particularly helpful scrolling screen it is now).

Things got fun at the Rosa Parks station, where we descended into the bottleneck that is the stairs to the Blue Line Platform to find a couple of Sheriffs waiting for us. They checked everyone that came through, making people anxious because the delay meant they were going to miss the train or buses they could see waiting below. At least they didn't have the canines with them.

For me, missing the train turned out to be a good thing. Because of the traffic jam created on the midpoint landing in the stairwell, I couldn't linger at the turnstile even though it refused to read my TAP card. So, I went through and on down the stairs, circled around the platform, lugged my suitcase back up the stairs, and passed through the turnstile again (it was faster and safer than leaving the platform, crossing the tracks, finding the validator near the TVM, and crossing back over the tracks), this time successfully. And just in time to catch the next train. Thanks, Sheriffs!

As the Canadian and I moved to the front of the train car to stand with our luggage, a thin, sweet-faced young man in shorts and a t-shirt motioned for me to sit down next to him.

I told him I preferred to stand since I had just been sitting for the last 6 hours.

Looking at him, I noticed he was hunched a bit and cradling his awkwardly bent left arm in his lap.

"Are you OK?" I asked, a little concerned. "Did you hurt yourself or are you just cold?"

He had had a stroke at age 17, he said, and was partially paralyzed on his left side. He had gotten some physical therapy at the time but now, at age 18, he had aged out of the foster care system (which he had been in and out of since age 2) and had lost both a place to live and the insurance that previously covered those costs. When he went to Skid Row looking to get access to services, his phone and some of his belongings were stolen. So, he was just riding the trains, trying to stay warm.

"But I got a ticket," he said, pulling a crumpled up ticket out of his pocket and handing it to me. "The Sheriffs stopped me and I tried to tell them my story, but they just gave me a ticket and told me to tell it to the judge and hope for mercy."

The ticket was from 3:30 that afternoon on the Red Line in Hollywood. It was now 7 p.m. and we were in Watts.

"You really have been riding all day, huh?" I said.

"Yeah, I gotta stay warm. With all the rain, that's been kinda hard," he said. "Somebody gave me this paper ticket and told me to try to show the Sheriffs that if I got stopped, but it didn't help me."

Of course it didn't. It was one of Metro's old paper tickets.

At that moment, the Sheriffs walked past the windows at the Florence-Firestone platform with a youth in handcuffs.

The Canadian gave me a WTF is this place?? look.

Don't you people have health care or social services, he wanted to know. And is this level of police presence typical everywhere?

Police presence and the aggressiveness of policing tends to depend on the neighborhood, I told him. With regard to services, I said, they do exist but foster youth are the least equipped people to navigate them. They are (generally) rather abruptly turned out into the world at age 18 instead of being transitioned through programs that might assist them with housing, education, or accessing of services. Even Metro had begun a pilot program last year to give passes to foster youth to ease their transition, but Clarence had obviously never heard of it.

Even if he had known about it, I don't know how easily he could have accessed the pass, anyways. Clarence was bipolar, among other things, according to him, something which seemed to be affecting his ability to accomplish basic tasks, like find shelter using the 211 services hotline. Apparently, he had been calling the number from a payphone but had either gotten impatient trying to make his way through the menus or waiting for an extended period to be patched through to an actual person.

"Nobody answered when I called," he said, staring down at the 211 flyer in his hands. "So, I'm riding the trains."

People sitting around him seemed to take him seriously and nodded sympathetically.

I gave him my card and told him to call me the next day.

"I'll call them and see what I can find out," I said. "I know there must be services for youth like you, but I can't tell you what they are offhand and everything will be closed up tonight."

"Thank you so much!" he said. "It would just help so much to have someone just try to find something. I don't know what to do except keep moving and hustling. But I'm a good person. I'm no gang-banger and God is on my side. I'm alive and I'm thankful for that. Nuthin' else I can do."

"Do you think he'll actually call you?" the Canadian asked, worried, when we got off at the 7th St. Metro Center.

"Oh, shit, don't forget to TAP the card again," I said as we jostled our way through the crowd toward the validator awkwardly placed along the railing leading to the stairs.

"Geez," he said. "Is this the only one? I would never have seen it. Or even thought about looking for one, I guess. Thanks."

"If Clarence was lucid, he'll call," I said. "But he's bipolar at the very least, and he's probably deteriorated a lot since being on the streets. Even though I think a lot of what he told us was true, I don't know that he will remember much of this conversation tomorrow."

The Canadian looked bummed out.

"I know," I said sympathetically. "I'm sorry. It's a real shame. That kind of thing happens all too often here, unfortunately. Um...welcome to Los Angeles?"