It has been a year since I reported on the Expo bike path’s Northvale Gap – something I’ve been doing in Streetsblog since 2015. I want to provide a quick update. But I also want to share my view based on decades of advocating for today’s E line and for safer bike and ped options. I see the Northvale Gap as the latest iteration of NIMBYism as old as my Cheviot Hills neighborhood whose history I have compiled at CheviotHillsHistory.org.

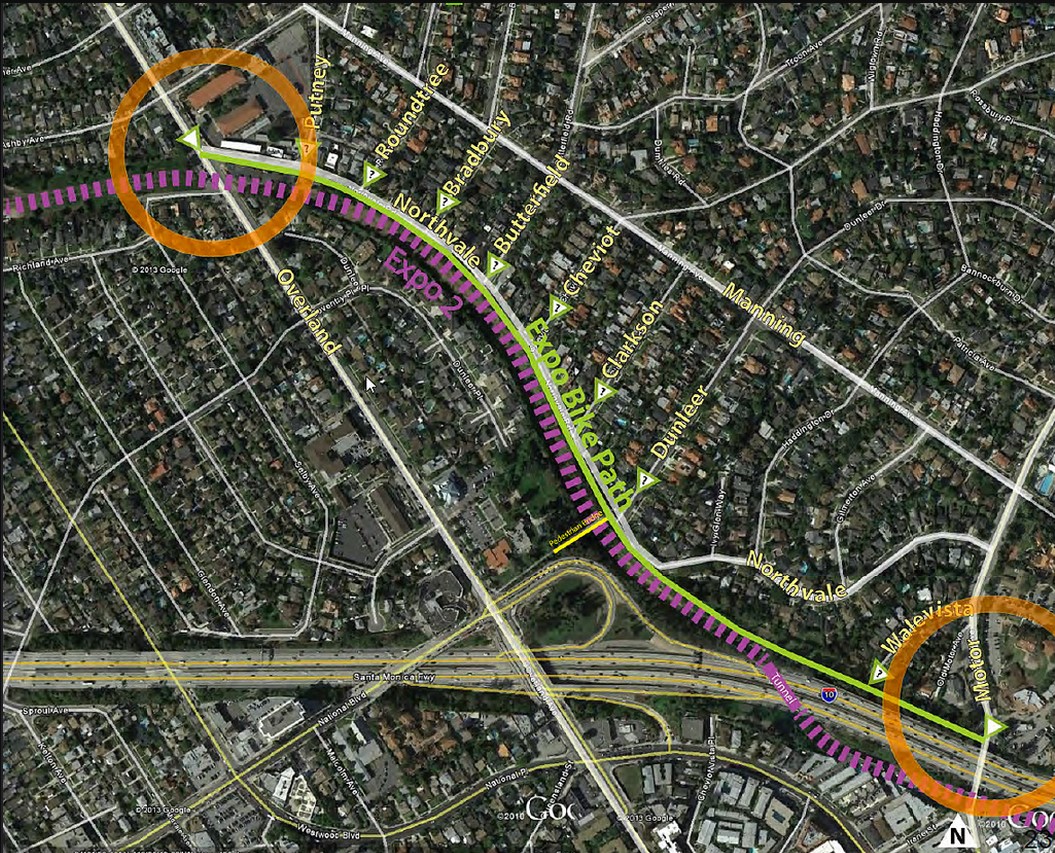

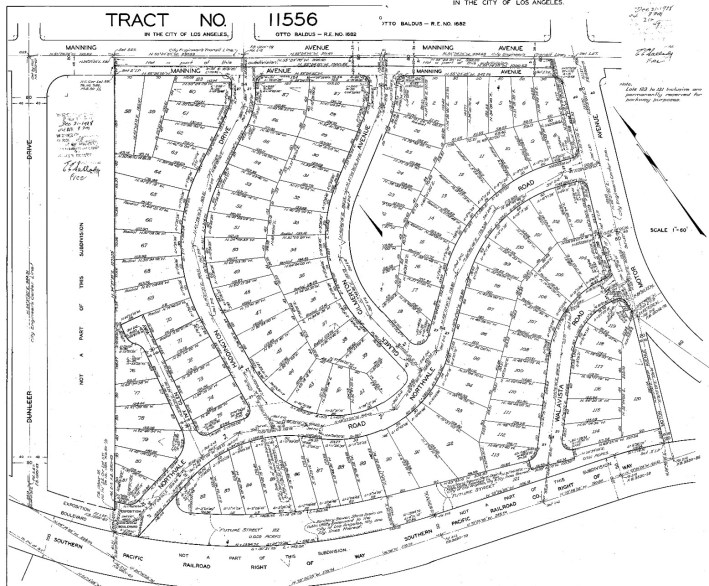

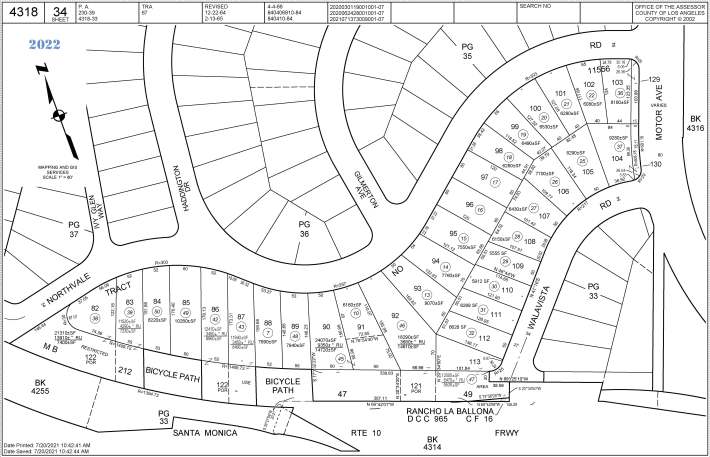

The Northvale Gap runs along the southern edge of Cheviot Hills. The western section of the path will be built along Northvale Road in the area subdivided and sold as Country Club Highlands in 1923, while the part of the path passing residents’ backyards will pass alongside Cheviot Knolls, which dates to 1938.

The following is not all chronological.

History: A train, future Exposition Boulevard, and then a noisy freeway, in their backyards

When Cheviot Knolls was built, Southern Pacific’s single-track electric freight and passenger railway (the latter popularly called Red Cars) ran on a 100-foot wide right of way south of 15 residential lots.

The city planned to extend Exposition Boulevard along the two parcels situated between the homes and the railway. For most residents, cars and people would be going by their backyards; for others, they would pass along their side yards.

That part of Exposition roadway was never built, but a sewer was installed beneath it.

The railway carried passengers until 1953 and freight until 1988. In the later years it was converted to diesel and was the subject of much consternation. In 1957, “Pacific Electric Railway … was ordered to minimize certain objectionable aspects of diesel train operations on its so-called Santa Monica Air Line.” “Under the order the railway must keep the right-of-way in a clean and orderly condition, must install rail flange lubricators on noisy curves, must clean out ditches between Overland and Motor Aves. to provide adequate drainage and must reballast and surface the track bed between these streets.” (L. A. Times, Nov. 21, 1957.)

The Santa Monica Freeway spoiled the plan to extend Exposition Boulevard.

Freeway planning started in the mid-1950s, and the freeway opened in the mid-1960s. Building the freeway meant moving the tracks; about half of the 15 homes are still next to the tracks, while the others are next to the freeway. Potions of the planned Exposition Boulevard right-of-way were used for both freeway and relocated rail.

Homeowners Add to their Backyards and Some Get a Freeway Soundwall

At some point – it might have been in the mid-1960s when the Santa Monica Freeway was built (and the train tunnel beneath it) – adjacent homeowners bought pieces of the “paper street” from the city. However, to maintain access to and integrity of the sewer beneath, no structures were allowed to be built on it. In any event, the homeowners got a buffer from both the train land and the freeway beyond.

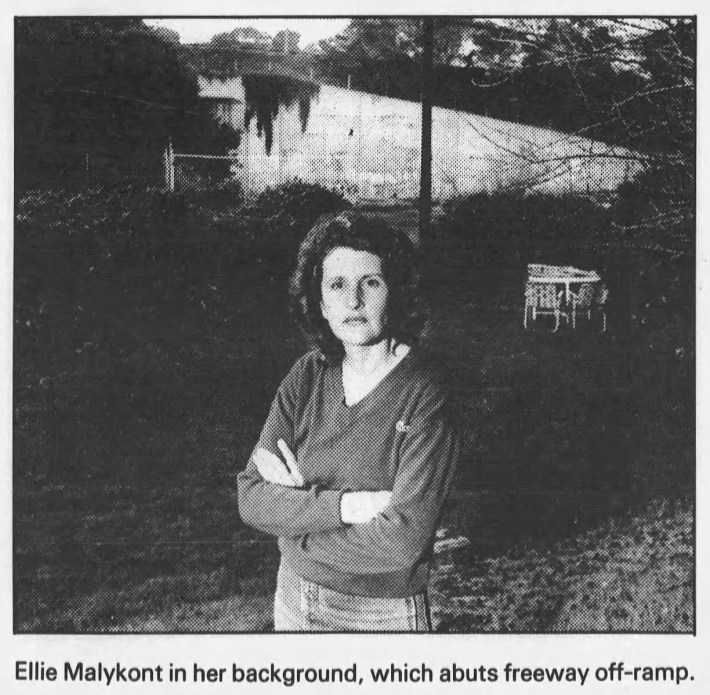

In the mid-1970s, land use attorney S. Zachary Samuels bought a house backing up on unbuilt Exposition Boulevard, the still-operating railway, then the freeway.

In a 1986 Los Angeles Times article about residents potentially paying for a sound wall, Mrs. Samuels is quoted complaining about the freeway noise: “We didn’t expect this sound at all when we moved here.” (L. A. Times, “Resident Would Pay for the Sound of Silence,” Jan. 5, 1986.)

Homeowners at the east end of Cheviot Knolls got their sound wall in 2006. Just west of there, the Samuels family and their neighbors would have to wait.

NIMBYs Fight the E Line

In 1990 the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (a predecessor of Metro) bought the recently disused railroad right of way, but “fierce resistance from some Cheviot Hills homeowners who feared the trains would bring noise and crime stalled” the passenger rail project that ultimately became the E Line.(L. A. Times, Dec. 4, 2004.)

The resistance continued. In January 2007, the Cheviot Hills Homeowners’ Association president wrote that it had taken “a formal position favoring light rail on Venice and STRONGLY OPPOSING light rail on the Expo right of way.” He cited (among other things) concern about how the line “would likely ‘play’ with realtors and potential homebuyers.” Meanwhile, he acknowledged “[t]wo of our Board members live on Northvale, and two others live a block away.” (HOA Website, Jan. 13, 2007.)

Some residents’ concerns were parochial and unsympathetic, with a previous homeowners association president asking: “Do you think the people who live in Cheviot Hills are going to take this bloody train. No, they are going to get in their cars. The people who are going to use this are the people who work in the hotels in Santa Monica, and they are going to come from the Hispanic areas nearer downtown. Now they take the bus.” (L.A. Times, Mar. 17, 2007.)

In other words, Not In My Back Yard – even if it means a longer ride for people “from the Hispanic areas” going between Santa Monica and Los Angeles.

NIMBYs Lawsuit Created "Northvale Gap" in Expo Bike Path

When the environmental documents were circulated for the bike path, several homeowners, represented by land-use attorney/homeowner Samuels, filed suit: Samuels v. Federal Highway Administration. For that story see my 2015 post. The lawsuit caused the State of California to pull its environmental certification, so the bike path was not built along with the E line as intended. Hence, the “Northvale Gap” in the path connecting Los Angeles, Culver City, and Santa Monica.

The first objection in the Samuels complaint was that “the Bikeway … will require the construction of a paved bike thoroughfare through what is now a green space which serves as a buffer between the I-10 Freeway and Plaintiffs’ homes ….” In other words, each Plaintiff literally pleaded, “not in my backyard.”

Homeowners Settle for, First and Foremost, Walling Off Their Backyards

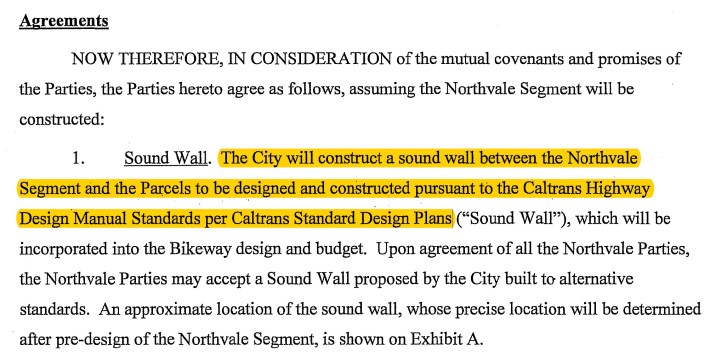

Point one in the Samuels’ settlement was that “The City will construct a sound wall … to the Caltrans Highway Design Manual Standards … which will be incorporated into the Bikeway design and budget.”

There was no public outreach when the city agreed to give residents their ransom – and to take the money from bikeway budgets rather than from, say, freeway budgets. Harkening back to the 1986 “Resident Would Pay for the Sound of Silence” article – it would be the taxpayers, not the Samuels or their neighbors who would pay for the sound wall.

Neither was there meaningful consideration of what it meant to install a sound wall built to “Caltrans Highway Design Manual Standards.” Indeed, the homeowners were not allowed to build over the paper street in order to protect the infrastructure underneath. It turned out that putting a heavy soundwall over sewers and storm drains raised more challenges, further delaying the project.

NIMBYs Install Illegal Gate on Pedestrian Bridge Locking Off Cheviot Hills at Night

In August 2013, Streetsblog reported on the Samuels settlement, noting that “Cheviot Hills has a 20-year history of blocking access to public rights-of-way.” referring to the gating of the Dunleer footbridge.

That pedestrian bridge connects Cheviot Hills to Palms Park. The bridge was installed to provide safe access to Palms Park after the freeway construction steepened the slope between the neighborhood and the Park.

“The footbridge gate was installed by the Dunleer Northvale Neighborhood Watch in the early-1990s, and it was later taken over by the Cheviot Hills Homeowners’ Association, whose 2005 newsletter says the gate was locked from 9:30 p.m. to 6:00 a.m.”

Despite my best efforts, I never found legal authorization for cutting off this public walkway.

Streetsblog presciently titled that story, “Will the Next Expo Battle Be About Access to the Bike Path in Cheviot Hills?”

NIMBYs Want to Limit Bike Path Access

Chevioteers have tried to, and may yet, limit access to the as yet unbuilt bike path. In September 2013, Ted Rogers (of Biking in L.A.) wrote a SBLA article reporting that people at a public hearing about the bike path were more concerned about limiting access from the path to their neighborhood than providing access to it on behalf of neighbors. “Access points were, in fact, one of the key points of contention.

A number of commenters – some of whom identified themselves as part of the seven who had filed suit – asked for no access points leading into their neighborhood between Motor and Overland, while others were willing to consider a single access point at Dunleer, roughly a third of the way through the neighborhood.”

Pernicious NIMBY History – Racial Covenants

Revisiting this litany of NIMBY episodes reminded me of the earliest efforts at exclusion from the neighborhood – those manifested in restrictive covenants.

In 1938, the Cheviot Knolls subdivision was proposed on the erstwhile Knob Hill Ranch. The Francis Land Company (belonging mostly to the Dominguez family, recipients of California’s first Spanish land grant) planned for 120 single family residences between the Cheviot Hills subdivision and the Santa Monica Air Line – the electric passenger and freight railway connecting Santa Monica and Los Angeles. Leimert Park developer Walter H. Leimert mapped lots for homesites while ceding land to the city of Los Angeles for roadways and, beneath them, sewer lines.

Like other neighborhoods in the area, it was for whites-only. As explained by California State University Dominguez Hills University Library archivist, Thomas Philo in “Perpetual and Binding Forever: Race and the Creation of a Los Angeles Subdivision,” to get the Federal Housing Administration’s approval to secure mortgage insurance, deeds restricted homeownership or residence to “persons whose blood [was] entirely that of the Caucasian race.”

After the United States Supreme Court kept courts from enforcing restrictive covenants with its 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer decision, attorney and author Stanley L. McMichael published Real Estate Subdivisions (New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1949). McMichael thanked Cheviot Knolls developer Walter H. Leimert for providing him with a “typical set of restrictions controlling the development of a medium-grade subdivision known as ‘Beverlywood’ in the city of Los Angeles, California.” And McMichael made the case for perpetuating racial separation in housing, quoting at length the argument of Philip M. Rea, president of the Los Angeles Realty Board, that “the insistence of some Negroes upon moving into areas previously restricted exclusively to the occupancy of Caucasians will necessarily create racial tensions and antagonisms and do much harm to our national social structure.” Rea (and by extension McMichael) continued: “To avoid these consequences and to stabilize the values of home ownership, it has become essential that an amendment be adopted to the Constitution of the United States, as herein proposed. This amendment should be made retroactive, so as to provide a remedy for those who have already suffered from the conditions mentioned. In the interests of fairness it should be so drawn as to assure Negroes of the enjoyment of areas restricted to the occupancy of their race, as well as to insure Caucasians of the enjoyment of areas restricted to the occupancy of Caucasians.”

Whether in Cheviot Knolls or Leimert Park, people fought residential integration because – among other reasons – they believed it would lower property values. Indeed, that became a self-fulfilling prophecy which led to blockbusting in areas including the initially whites-only Leimert Park which became the heart of Los Angeles’ African American community through blockbusting where Black families moved in and panicked whites moved out.

Much has been written about the continuing costs of restrictive covenants even generations later. It is no coincidence that some of the people and communities who use public transit or bike by necessity (rather than choice) are among those who were kept from building family wealth.

Home Stretch?

Have we all now paid enough for Northvale homeowners’ mistaken impression that moving next to a freeway would be quiet? Forty years later, they will get their sound wall. And taxpayers will all pay an order of magnitude higher cost for the bikeway project.

As for the regional commuters who lost a practical and healthy alternative to driving – well, take heart in knowing you were not the first to be kept out – and that the underfunded bicycle infrastructure accounts will get to pay for that sound wall.

By juxtaposing racial covenants with the bike path NIMBYism, I am not equating them. Minorities barred from buying or living in wealthier, white neighborhoods were not affected in the same way as people who now have their mobility restricted through them. People who participated in restrictive housing agreements (especially those who actively sought out such arrangements) consciously discriminated based on race, a far more insidious act compared to seeking to stop people from biking past their backyards.

As for finally closing the Northvale Gap, I am cautiously optimistic now that Katy Yaroslavsky is the Los Angeles City Councilwoman for Cheviot Hills. She is pro-active-transportation and is also on the Metro board. Already, her office has obtained additional funds from Metro to close the Northvale Gap. Her staff regularly meets with relevant departments (LADOT, Engineering, City Attorney) to solve problems. The latest (2022) fact sheet available through LADOT’s “Exposition Bike Path (Northvale Segment)” website says “Construction is anticipated to begin Spring 2024.” The Council Office expects construction to start some time in 2024.

Jonathan Weiss practices law and lives in Cheviot Hills. He is also a boardmember of Streetsblog L.A.’s parent nonprofit, the California Streets Initiative.