On Friday, Metro's second tunneling machine broke through at the future La Cienega Station. Construction on the Westside Purple Line Extension Section 1 project (WPLE1) is now 70 percent complete, with more than 98 percent of tunneling safely completed.

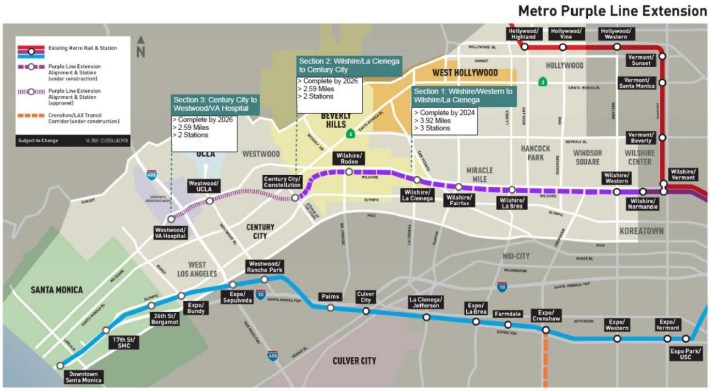

Metro is extending its Purple Line (now renamed the D Line) subway westward in three sections. The $3 billion WPLE1 will extend the line 3.9 miles under Wilshire Boulevard from Wilshire/Western Station to a future temporary terminus at La Cienega Boulevard, now expected to open to the public in 2024. From there, two subsequent under-construction phases will continue west. WPLE2 will extend the line to Century City (anticipated in 2025) and WPLE3 will extend to Westwood (in 2027).

WPLE1 construction began in 2014. Tunnel boring got underway in August 2018 and was anticipated to take about two years. Metro’s twin WPLE1 tunnel boring machines (TBMs) initially dug east from La Brea Avenue to Western Avenue. The TBMs were then transported back to La Brea and launched westward in October 2019. Tunneling under Wilshire west of La Brea – in the vicinity of the La Brea Tar Pits – Metro encountered difficult soil conditions, including tar, methane gas, and more. As of October 2020, those difficult conditions resulted in the extension's anticipated opening being moved back from 2023 to 2024 - as well as a $200 million (seven percent) WPLE1 budget increase.

Last week, Streetsblog published a post outlining some of the difficulties that Metro persevered through in tunneling on the WPLE1. After that post, Streetsblog received more of the WPLE1 tunneling story via a conversation with Jim Cohen, Metro's Project Director for WPLE1 and Dave Sotero, Metro Communications Manager. Unless otherwise specified, the project details below are all from Cohen.

Sotero calls WPLE1 "easily most complex engineering feat in the modern history of Metro rail construction." The project encountered very challenging geologic conditions, which will continue for the next two Purple Line Extension sections.

Cohen and Sotero both spoke highly of Metro's contractor Skanska Traylor Shea, which brought extensive tunneling experience.

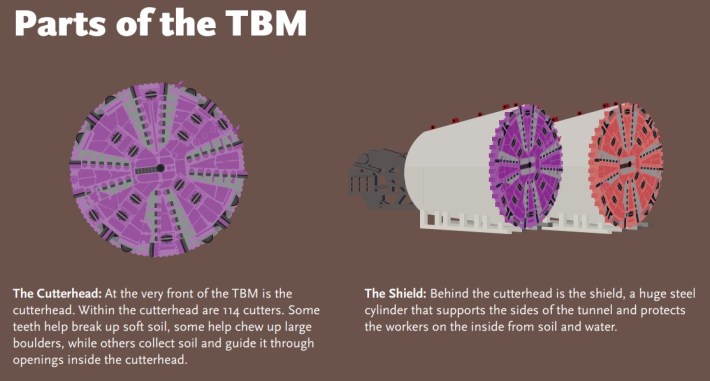

Tunneling is one very challenging aspect of Metro rail construction. For WPLE1, Metro utilizes two massive TBMs - each being 21.5-feet in diameter and 400 feet long - to dig through soil kind of like a massive worm. At the front of the TBM is a rotating cutterhead that does the digging.

Right behind the cutterhead is the TBM shield, which houses several complex mechanisms. Inside the shield, equipment rotates the cutterhead, and begins moving earth toward the tail. The body of the TBM has a long conveyor belt that transports dirt all the way to the rear.

As the digging proceeds, crews inside the shield install the tunnel lining. The permanent tunnel structure is made of pre-cast concrete liners.

Because the WPLE1 alignment travels through gassy soil - with tar sands and methane pockets - the tunnel lining is especially robust. The pre-cast concrete liners are fitted with double gaskets (made of a rubber-type material) and tightly bolted together. There is no concrete-to-concrete interface which could create a gap or seam. The system stops any leaks, whether water or gas, from getting inside the tunnel.

(For readers interested in better understanding how TBMs work, see videos on London Crossrail or British Columbia Evergreen.)

Cohen noted that, very early on, Metro was aware that there are various abandoned oil wells along the WPLE1 alignment, with some of these wells so old and abandoned such a long time ago that their locations are not well documented.

Metro had planned to, when nearing the location of an abandoned oil well, have construction crews probe ahead of the cutterhead. Essentially the crew would extend a rod through the cutterhead, then use a magnetometer (a fancy version of those metal detectors some people use to find lost coins at the beach) inserted into the rod to check ahead. Though initially in the contract, this type of probing was not performed for WPLE1, due to its limitations in spotting problems in advance. Probing in front of the cutterhead level can spot metal a maximum of about 200 feet ahead, which doesn't give crews much time to react.

Instead, Metro's contractor used horizontal directional drilling (HDD) to allow magnetometer probing well in advance of the TBM.

For HDD, a construction crew set up in the middle of Wilshire Boulevard and used a tracked drill rig to drill a ~4-inch diameter more-or-less U-shaped tunnel. The hole goes from the street surface down to the level of the subway tunnel, then horizontally along the path of the subway alignment, then vertically back up to the surface. The hole was lined with plastic pipe, then a magnetometer was pulled through the pipe to detect metal.

Metro crews did HDD/magnetometer investigations for the entire reach from Fairfax Avenue to La Cienega, doing five different runs over the roughly half-mile stretch. This technique revealed what Metro believes is an abandoned oil well at the intersection of Wilshire and McCarthy Vista/Crescent Heights Boulevard. In order for Metro TBMs to avoid colliding with the obstacle, Metro re-aligned the project, swinging both tunnels about 10 feet to the south.

This minor re-alignment took place about a year ago, and was successful. Both TBMs got past McCarthy Vista without hitting the obstacle.

Further west along the subway path, an HDD/magnetometer probe spotted an "anomaly" near the middle of the intersection of Wilshire and San Vicente Boulevard. This was not in the vicinity of any anticipated oil wells.

At this month's Metro board Construction Committee, Boardmember Fernando Dutra questioned Metro Chief Program Management Officer Richard Clarke on what he meant by an "anomaly." Clarke responded, "we call them anomalies until we know what it is - and anomaly is a dirty word around here." Clarke clarified that in this case the anomaly was found to be "a piece of steel large enough to damage the [tunneling] machine."

Damage to the TBM could have had huge consequences. In Seattle, a damaged TBM shield resulted in a two-year delay. Serious damage to the cutter head or to large equipment in the shield, like what happened to Bertha in Seattle, could necessitate extracting the TBM by digging down from the surface. For WPLE1, this process could have meant severe delays and an extended closure of Wilshire Boulevard.

With magnetometer readings indicating a hunk or hunks of metal likely to be blocking both of the tunnels, Metro needed a plan.

Basically the strategy was to harden the ground around where the metal was expected, then augment the TBM utilizing a 5,000-year old technology - people with shovels - to dig out the metal. Though it's a bit more complicated than that.

The plan ultimately required multiple jurisdictional approvals, including from the cities of Los Angeles and Beverly Hills, as well as the Los Angeles County Flood Control District, due to their large storm drain below San Vicente.

Firming up the ground deep below meant injecting chemical grout from the surface - from the middle of Wilshire and San Vicente. This necessitated lane closures and traffic management measures.

In a 45-foot long stretch of Wilshire, Metro dug 211 ~4-inch diameter vertical column holes to inject grout. The columns had to carefully avoid underground utilities. At the surface, the holes were started via a process called potholing - where big vacuum trucks use water and suction to remove a column of earth. Once the surface pothole column was deep enough to be past utilities, then crews drilled to get the hole down to subway level.

Much of the vertical potholing/drilling was done from the street. In the middle of San Vicente (below the street, but still well above the level of the subway tunnel) there is a box culvert storm drain - about 18 feet by 18 feet. For the storm drain area, crews went down inside the drain and from there drilled holes down through the floor of the concrete culvert.

When the column reached the desired level - just below the subway tunnel level - a tube was inserted into the column, and a grouting chemical was pumped into the tube. The column spreads chemical grout out in a 4-foot diameter column. The 4-foot diameter areas overlap to form an interlocked grout block. The grout is firm enough to prevent excessive subsidence or cave-in, but not too firm for the tunneling machine to get through.

At that point - in late 2020 - Elsie the north TBM, which had been held back outside the grout block, advanced. Slowly.

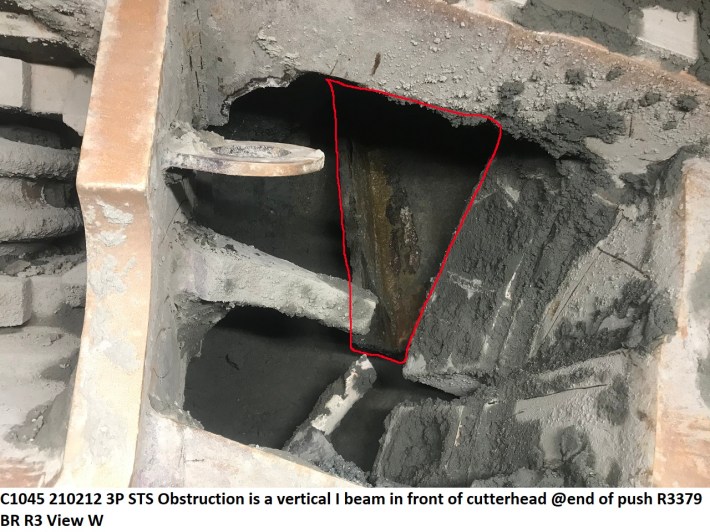

In the vicinity of the anomaly, tunneling work alternated between mechanical mining and shoveling by hand. Miners - workers with shovels - climbed in and out through the cutterhead, using the same gaps that allow dirt to get through the head. With the grouted earth ensuring that they were protected from soil caving in on them, the miners would advance a foot or so, then go back through the head and shield, and allow the TBM to advance a foot or so. Then the miners would come back through and shovel again. And again. And again.

All the time, the miners were looking for the metal obstruction that HDD/magnetometer had detected.

They found it. There was an H-pile, a steel beam weighing about 118 pounds per foot. It was protruding 3.5 to 4 feet into the path of the tunnel, vertically from near the top. The workers brought in torches and cut the metal off, giving the tunnel machine a margin of about one and a half feet below the remaining portion of the steel beam. The tunneling process fills the area around the tunnel with grout. Between the grout, and friction between the metal and the earth (that makes it tough to drive piles), Cohen expressed that he is fully confident that the beam is not going any place and that it poses no potential issues to Metro's tunnel.

The miners torched the H-beam into small pieces and brought them out via the gaps in the cutterhead.

With the obstacle removed, the north TBM made it the remaining three blocks (about a quarter mile) to La Cienega with no significant issues. The TBM broke through there in late February.

After the north TBM made it through San Vicente, Metro followed a very similar process with Soyeon the south TBM. The south machine miners found a similar steel pile and the same procedure was used to remove it. Soyeon broke through at La Cienega on Friday.

Metro notes that, despite costing additional time and money, the grout block plan performed really well. Miners were able to safely go out ahead of the TBM, with no injuries. There was very little surface movement in that intersection. Metro staff praise the hard work performed by their contractor.

Though the extension's first section will end at the future La Cienega Station, the twin TBMs work is not quite done.

Elsie and Soyeon will now dig two 550-foot tail tracks west of La Cienega. At the end of the tail tracks, Metro will install a low-strength concrete block that WPLE2 TBMs, named Harriet and Ruth, will tunnel through to connect with WPLE1. Harriet and Ruth are already tunneling east from Century City, and are currently below Beverly Hills High School.

(SBLA had reported on an earlier plan to leave the WPLE1 TBM cutterheads in the earth, but now Metro confirms that they will be "torched out" - cut up into pieces and removed.)

The added work to extract the steel beams did result in some delay, and some cost escalation. Metro is currently evaluating the situation with plans to bring the cost increase to the board after April.

Metro still doesn't know how the steel beams got there.

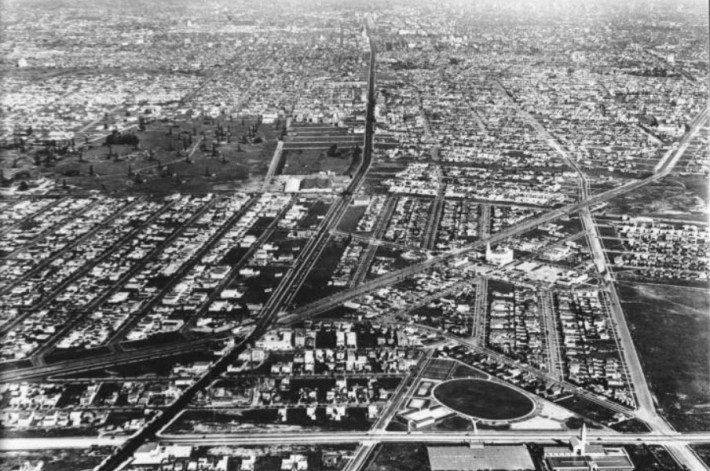

Streetsblog doesn't know either, and at this point it hardly matters, but some 1920s aerial photos have fueled some amateur speculation.

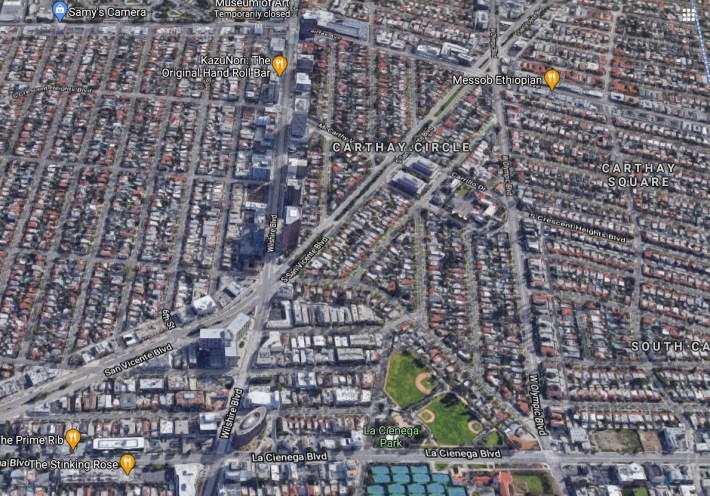

For context, above is a contemporary aerial photograph via Google Maps. To make it match the aerials below, the image is shifted - with north to the left. Wilshire runs from to top to bottom, and San Vicente runs from the lower left to the upper right. The Purple Line extension tunnel is below Wilshire; WPLE1 ends at La Cienega Boulevard, at the bottom of the photo.

In early aerials (see the 1922 photo above), there is a creek that ran beneath the intersection of Wilshire and San Vicente. Today's six lanes wide plus median San Vicente Boulevard was then the San Vicente line of the Pacific Electric Railway. It is possible that the metal beams that Metro's TBMs encountered were part of some early structure that elevated the rails and/or roadways of San Vicente and Wilshire to get them over the creek.

Note also in the center left of the 1922 photo, lots of oil wells in the area that would later be Park La Brea and its surroundings.

The area urbanized through the 1920s, though the oil wells persisted.

Wilshire was an important artery for early Los Angeles' expansion westward. The Wilshire corridor - a broad swath of Southern California from downtown L.A. to the Westside - is among the denser parts of the country, with high concentrations of homes, jobs, retail, and cultural institutions. With Metro extending the subway another nine miles under Wilshire, Angelenos will have faster and more high-quality options for traveling the corridor.