L.A. City pulled the plug on a plan to make some westside streets safer for walking and bicycling under COVID-19. Mobility advocates are pushing for the program to be done in ways that truly serve the health of communities across the city, especially underserved neighborhoods.

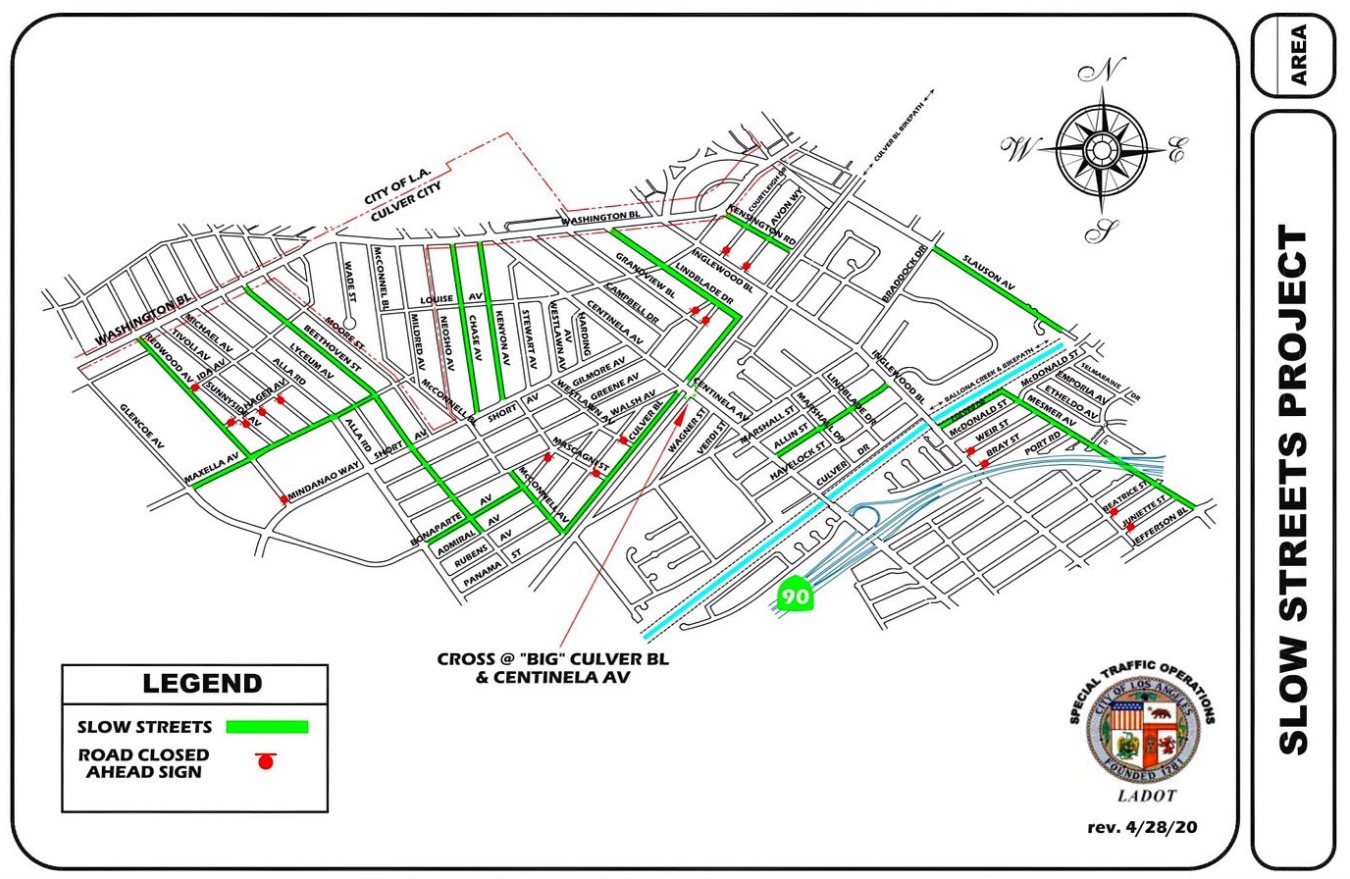

Wednesday, the Del Rey Neighborhood Council shared via Twitter an L.A. City Transportation Department (LADOT) map showing the city's first plans for "slow streets" improvements designed to make walking and bicycling healthier during COVID-19 safer-at-home orders. The program, the first of its kind in the city, was announced to start Thursday - yesterday.

A few hours later, the Del Rey council walked back the announcement, noting that the city had chosen to postpone the project.

Numerous cities big and small have implemented quick-build safety improvements to allow for safe walking and biking during COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. Streetsblog Chicago reported that the big city list includes New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Boston, Madison, St. Paul, Minneapolis, Denver, Salt Lake City, Seattle, Portland, Oakland, and San Francisco - with several smaller cities also taking part. SBUSA has a piece today on some best practices.

Streets for All, the Del Rey Neighborhood Council, and L.A. City Councilmember Mike Bonin have shown early leadership in a campaign for quick street improvements. Streets for All joined with twenty other co-signers on a letter urging L.A. to install temporary street safety improvements under shelter-at-home orders.

But none of these folks were pushing for just one pilot limited to one neighborhood--they had hoped to see a series of streets serving neighborhoods across the city. Bonin urged that a broader city program support "seniors, families with children, and people with disabilities... renters and people living in multi-family buildings without a yard." The advocacy letter calls for a broad network serving "equity, mental health, safety, and the physical well-being."

A lot would hinge on a single neighborhood creating safer streets. If successful, it could serve as proof of concept and lead to expanding the program to other neighborhoods. In a worst case scenario, a single neighborhood could lead to CicLAvia-like crowding that would bring an end to the pilot, and lead to charges that "we tried that here and it just doesn't work in Los Angeles."

Wednesday, responding to a question from L.A. Times reporter Laura Nelson, Mayor Eric Garcetti outlined his position on whether L.A. would be moving forward with safety improvements similar to other cities. Garcetti responded (listen here, starting at minute 21) that he is "very supportive" of doing these "in many parts of the city," but:

I think it's really critical how we do it and when we do it. That we not--as we saw at the beaches, there's some places, you know Australia's opened their beaches, from 6-9 in the morning, to exercise. It's been a successful way to open beaches. We saw pictures in Orange County that looked maybe, potentially, less successful this weekend. So it's very important not just that we take action, but that we do it the right way.

It could draw too many people to one area, it could be something that spreads the disease.... especially [for] people who live in dense parts of the city who don't have any place to go... if we can find a street we can safely close, and a network of an area (so people don't go to one area but... everybody has places close by), that is the criteria that I have asked my team to look at...

Garcetti stated that he has formed an internal city working group focused on the program, which he says includes councilmembers' offices, LADOT, and the Bureau of Street Services. What seems to be missing from this working group is connections with community-based organizations that can provide on-the-ground know-how.

Streetsblog spoke with L.A. County Bicycle Coalition Executive Director Eli Akira Kaufman, who is supportive of improvements but expressed caution in how it might be done.

Kaufman strongly encouraged L.A. to adopt Seattle's program name, "Healthy Streets." Open streets already refers to CicLAvia-type events. Slow streets, as LADOT is currently calling the program, doesn't address the need to prioritize health.

Kaufman encourages the city program to proceed cautiously, with special attention to two criteria: health and equity.

First and foremost, Kaufman points out that the design needs to strongly minimize the risk of COVID-19 spread. People really do need to stay at home, as public health authorities are ordering. Any street improvements need to support physical distancing, and to support and/or improve mobility for essential workers getting to their jobs.

To foster equity, Kaufman encourages the healthy streets network to not be available merely on a first-come, first-served basis, which tends to favor improvements in better-resourced neighborhoods over ones that have been historically underserved. Kaufman also expressed concern over excessive law enforcement presence (as happened on an initial New York City pilot). Kaufman would like to see neighborhood-level leadership initiating the improvements.

Kaufman points to the directions called for by members of the Untokening collective in their response to the Coronavirus pandemic, including:

- Do not plan future projects at a time when equitable public participation is impossible.

- Center those most in need in any transportation improvements and connect them with services such as food distribution and medical care. Access to mental health care is essential.

- Define street safety in a way that centers the most oppressed and vulnerable groups.

There are a lot of factors to take into account in crafting a broad - at Kaufman's urging, SBLA will call it - "healthy streets" initiative.

The COVID-19 epidemic is dealing a severe blow to disenfranchised peoples - including Black communities, low-income people, and people living in overcrowded conditions (including many immigrant essential workers). Fast-moving cars are not the only - or the main - thing that prevents them from being able to access their streets. Where streets are contested, residents already limit their time outside or how far they travel on foot or by bike. In gentrifying areas, long-time residents who have been culturally erased from the landscape and who are still over-policed and impacted by street politics may not have the same access to their streets as better-off newcomers. In such cases, simply "opening" a street won't benefit them or make it more welcoming, and could instead be more alienating. Intentional programming may be needed to engage residents and ensure they feel safe, to offer services, resources, or information to assist them in surviving this difficult period, or even to create space for grieving and healing, as so many who have lost loved ones in these communities have been unable to be at their bedside or graveside.

Serving communities could mean combining healthy streets with other COVID-19 services, like food distribution - LAUSD, senior food programs, street vending - all done carefully, with distancing. These healthy streets would serve broader health needs than just walking and bicycling.

A cookie-cutter one-size-fits-all top-down program is unlikely to serve the broad spectrum of L.A. neighborhoods, and especially the needs of historically underserved communities.

Cities need to craft healthy streets pilots that serve numerous neighborhoods, not just the first or loudest. If a healthy streets program only serves to advance health and safety for already well-resourced communities, then it worsens existing inequalities - including health outcomes.

City staff need to listen to and respond to community concerns. Temporary materials can allow for relatively quick responses to shift healthy streets in response to on-the-ground conditions and community feedback. Community involvement and stewardship can craft solutions that improve healthy and safety, and build community.

Crafted properly, timed right, and implemented respectfully, there could be many positive outcomes from healthy streets.