To listen to opponents of bridge housing and shelters in Greater Los Angeles, one would get the impression that somehow these buildings are part of what is exacerbating the region’s homelessness crisis by drawing more people experiencing homelessness to Southern California and not part of the solution. Online message boards and social media are filled with posts about fears of “outsiders,” growing encampments, and attracting more people experiencing homelessness to one's neighborhood.

If one takes the time to visit area shelters, the on-the-ground truth is different.

Before a tour of Ascencia, a 45-bed family-friendly bridge housing provider nestled in the southeast corner of suburban Glendale, I walked around the adjacent suburban neighborhood. There were no encampments or loitering issues. A short discussion with two neighbors showed benign ambivalence (“It’s been in the neighborhood longer than I have. It’s never been a problem.”) and support (“I’ve cooked there for the residents and will again.”) for the shelter.

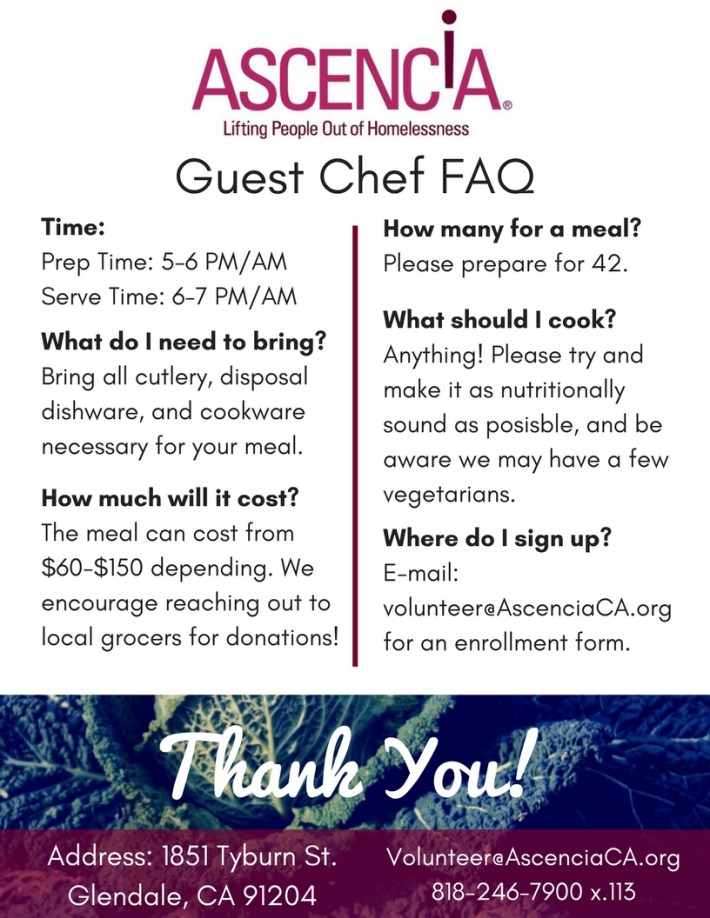

"Every community is different of course, but we're lucky to have the support of our community," explains Dr. Laura Duncan, the executive director of Ascencia. Duncan notes that the guest chef program mentioned by a neighbor has been a key part of Ascencia’s outreach to its housed neighbors for well over a decade, offering daily opportunities for community members to interact with people experiencing homelessness.

"In 2006, Ascencia broke off from PATH. At that time, our guest chef program was already running. It's been going ever since," says Duncan. Ascencia has found that community opposition and NIMBYism decrease significantly when neighbors spend time inside the shelter and share meals with shelter guests.

The guest chef program is one of the most visible commitments among Ascencia, the housed Glendale community and Ascencia's clients. Ascencia staff members organize a volunteer list of nearly 1,100 people to provide food for the 45 Ascencia Emergency Shelter residents. The calendar covers every single meal, but occasionally there are snags. Still, roughly 90% of the meals served at Ascencia are from the guest chef program.

Sometimes the meals are bought or donated by restaurants. Sometimes they are prepared on-site. A cookout in the parking lot prepared by the Glendale Fire Department is an oft-mentioned meal, but churches, Kiwanis clubs, car dealerships, and other civic groups donate their time and resources to feed their neighbors.

This has led to the larger community having a greater understanding of - and appreciation for - the lives of Ascencia's residents.

“The guest chef program is very popular. People enjoy doing it, and it serves two very important purposes: one is that the community feels a sense of ownership of Ascencia, they feel a part of it because they volunteer," says Assemblymember Laura Friedman, who represents Glendale.

"Second, it really humanizes their clients. People go there are surprised to see people from all walks of life, people that are community members. They are no longer ‘other’ people, but part of their community.”

Friedman, a former Councilmember and Mayor of Glendale, recently awarded Ascencia “non-profit of the year,” in part because of its efforts to engage with all members of the community. She has also volunteered with Ascencia.

“The first time I went, I didn’t know what to expect. They serve a diverse population, many of whom are working, and families…people from all walks of life,” she explains.

Unlike downtown L.A.’s El Puente, which Streetsblog profiled last month, Ascencia is a family-friendly shelter. Separate rooms are set aside for families, new mothers, and people with children. Residents who are not in families are grouped by their preferred gender identity, and free to choose which room (and access to which bathroom) they prefer.

Ascencia does criminal background checks on adults entering the shelter, roughly 90 of the 1,200 people they help annually. a controversial practice which Ascencia says is necessary to maintain the safety of children residing in the shelter. Even people without any sort of criminal record may balk at having their background explored, although Ascencia staff has no record of someone balking. Other homeless advocates argue that excluding people from accessing services because of past mistakes can exclude people who are working to improve their living conditions. Ascencia staff notes they are in Ascencia is in strong agreement with this position for all of its other programs.

A recent article by the National Alliance to End Homelessness argues that background checks are not just a barrier to those seeking to get housed, but also that there is a racial bias to this criteria, due to the disproportionate sentencing and prosecution of African Americans.

Twelve percent of the U.S. population is African American; however 40% of the population experiencing homelessness is African American. That’s a big difference. The criminal justice system disproportionately arrests and convicts people of color. Currently, many housing providers use criminal records as an excuse to say no to people of color seeking housing, whether purposely or inadvertently.

Duncan contends that criminal background checks are necessary to make sure that no clients have a violent, criminal background. “We have a lot of parents with minor children,” she explains. “We can’t place children in the same space as someone who has a history of violence or is a registered sex offender.”

Ascencia also works with the City of West Hollywood to provide bridge housing to that city’s homeless residents. As SBLA covered last year, many in West Hollywood's homeless population are fleeing sexual or physical abuse, or neglect, due to hatred of who they are. Ascencia’s policy of allowing transgender and non-binary clients choice in where to sleep and what facilities to use makes them a good fit, even if the two cities aren’t exactly neighbors. Current law only requires shelters to admit people regardless of identity, and there's talk about removing this protection at the federal level.

West Hollywood does not have a permanent shelter in place, so they work with Ascencia to provide bridge housing options for their homeless residents.

"This is a newer partnership for us. They came on in our last social services proposal in 2016," explains Corri Planck, the Manager for Strategic Initiatives for the city of West Hollywood. "As of their last set of program reports they've housed fifty people who were formerly homeless in West Hollywood." WeHo's outreach efforts and reliance on hard data were profiled in a Streetsblog article last year.

Ascencia has a two-person dedicated outreach team based in West Hollywood. They rent space from a church. Ascencia's team works with the city’s outreach teams. They visit public places, such as the library, where more personal outreach could occur. Homeless West Hollywood residents willing to leave the city for shelter are provided with bus fare to get back and forth from Ascencia, or sometimes even ride with Ascencia staff. Some clients need to make the trip daily for appointments with social services or counselors.

"They have tough work, helping people to get into housing," says Planck of both West Hollywood's employees and the extended team with Ascencia and other contractors. "And it's not just getting people into housing, but helping them remained housed."

While Ascencia has earned praise for its outreach in Glendale and West Hollywood, Ascencia clients face real challenges and there is a lot of work to be done to help them improve their housing situation.

With some small exceptions, such as families with children and infants, Ascencia serves as an evening and morning shelter: a place for people to find refuge from the streets, to be clean, to have appointments, and to eat healthy food. Even though only 13% of residents are employed, they are expected to be doing the work needed (getting ID, securing an income, saving money) to move from Ascencia to a more permanent residence. Children are enrolled in the Glendale Public School system.

"People can’t get too comfortable here. They need to be out doing what they need to do to get themselves out of this situation,” explains Duncan. Ascencia is meant to be a temporary haven, not a permanent solution.

Once in the program, residents have access to a range of professional, personal, and mental health services. Staff is multilingual. If specialized counseling is needed, Ascencia even has a video conference room and access to professional psychiatric counselors in another part of the state.

The goal is to get people into and out of Ascencia as quickly as possible. Stays at bridge housing and emergency shelters are supposed to last no more than 60 days for individuals or 120 days for families. While Ascencia tries to keep to this standard, its residents often require more time. This is due to the region’s shortage of permanent housing. It is more difficult because many of Ascencia’s clients are elderly, disabled, or face other barriers to housing - beyond money and credit scores including discrimination based on their race, sexual orientation or just because they are experiencing homelessness.

“A lot of these [bridge housing time limit] policies are national. They don’t take into consideration the nuances for different areas,” explains Duncan. "Most of the time, the kind of person who can get into permanent housing in a short period of time won’t rank high enough on the index to get into Ascencia in the first place."

Admission to Ascencia's program is based on need and a vulnerability index that takes into account several factors, including whether or not the person has access to other housing options (friends, family), whether they have dependents or children, how physically healthy they are or whether they have special needs, if they are seeking shelter from abuse, and their age.

"You might have a score of 8, and have been at the top of the list for a month. But if someone scores a 9 in an interview the morning a bed opens up, then they'll get the spot," Duncan explains. This means that many of Ascencia's clients are either high-risk or high-vulnerability people that are elderly, have disabilities, are escaping abuse, or have younger children.

Glendale was an outlier in 2019’s countywide homeless count. The city saw a drop from 260 homeless residents in 2018 to 243 in 2019 while the region saw a sharp spike. But just because Glendale saw a one-year drop, doesn't lesson the sting of the regional crisis.

Both Friedman and Duncan agree that the regional lack of affordable permanent housing is the biggest obstacle to getting people through temporary bridge programs into permanent homes. This is a problem in Glendale, West Hollywood, L.A., Santa Monica, and throughout the region.

“We know there are 59,000 homeless people in L.A. County, most of whom are probably low- or extremely-low income, " explains Duncan. "When you consider the number of people that have subsidized housing that are not homeless - they are moving, are staying with relatives, etc - those people are probably numbered a lot higher. On any given day, there are 300 units [of permanent supportive housing] on the market. To me, it’s amazing that staff here, or other non-profits, can find housing for clients at all.”