“Momma, look at me! I look good, huh? Look what you did. I’m fly, huh.”

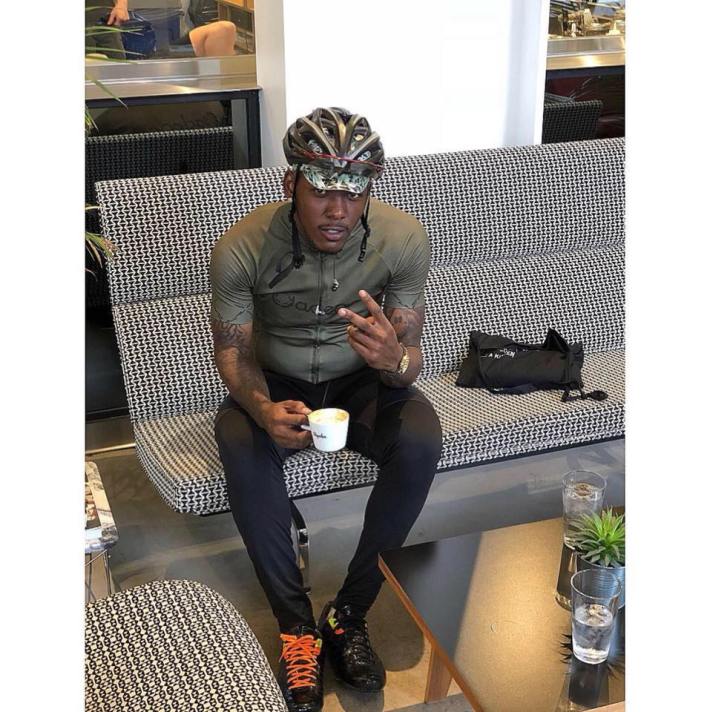

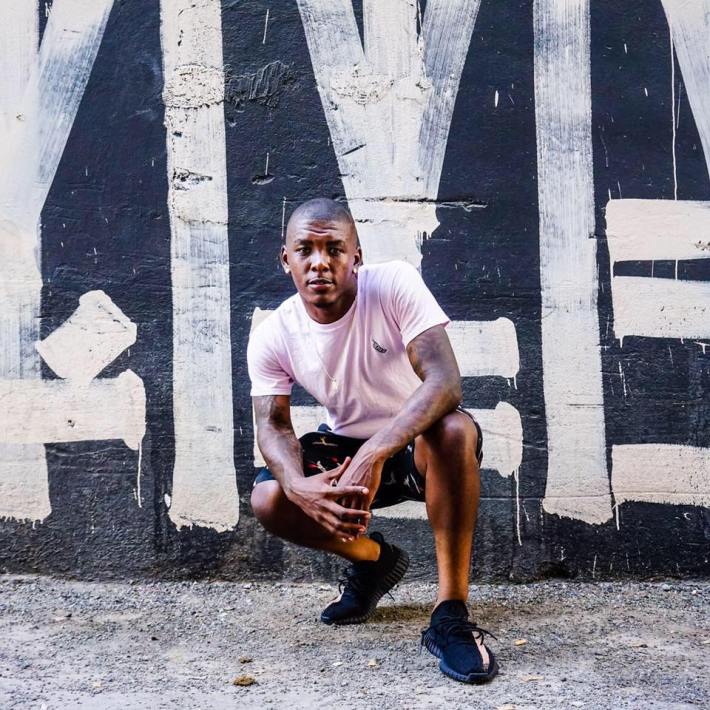

Twenty-two-year-old Frederick “Woon” Frazier was standing in the kitchen in a new cycling kit, flexing the thickly muscled thighs he had recently gotten tattooed with “My Bike” and “My Life.”

Beverly Owens Addison looked up at her son from the bed that takes up much of the space in the living room in the cramped one-bedroom apartment they shared with her husband.

“You look nice, Jun Woon,” she says she replied.

“Look what you did. Look what you created!” he repeated, still marveling over how strong he had become. “I love you, Momma - you know you my queen.”

“I love you, too, son,” she said.

“I’m about to go out here, I’m bout to ride my bike. I’m bout to have me a good day,” he said, smiling. “I feel good today, Momma. Man, I’m free.”

She knew he didn’t feel as free as he tried to make it sound. Part of his kitchen bravado was him psyching himself up to take another shot of insulin. He had been diagnosed with Type I diabetes at age fifteen after falling into a diabetic coma. Early on, it required him to self-administer insulin three times a day. Since getting more serious about cycling, he had dropped weight and been able to reduce the number of shots to two a day, but he still found being sick exhausting.

Ms. Beverly says he would occasionally complain that he was tired of the insulin and the pain. He hid it from most people, including her, she says, but it was bad enough to make him cry every now and then. It hurt her to watch him go through that. She dealt with it by trying to make sure he had everything else he needed.

“Did you eat?” she asked.

“Momma,” he laughed, “I fucked that burrito up like Gracie!”

She glances over at Gracie, the silky-coated young pitbull that Woon had rescued as a puppy after seeing her get tossed out of a truck a few years earlier and sighs.

“That’s the absolute last words he said,” she says. “The last words out of his mouth - ‘I fucked that burrito up like Gracie.’ And he was gone.”

Five minutes later, he was dead.

___

The fateful turn Woon took onto Manchester that sunny spring day was not the direction he normally would have gone.

But he had gotten a call from a friend and fellow rider who needed six dollars for a new inner tube.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that if the debris that lines Los Angeles’ streets doesn’t regularly make mincemeat of a bike’s inner tubes, the potholes and cracks eventually will. For cash-strapped lower-income folks who depend on their bikes for transportation, this can cause quite a hardship. And Woon wasn’t the type to leave a friend without wheels.

So instead of heading straight up Normandie, he made a right turn into what should have been the relative safety of the gutter lane.

Although usually heavily cracked and dotted with parked vehicles that can pose a danger (should someone unexpectedly fling open a door), gutter lanes can offer cyclists rare, if narrow, unoccupied real estate in a city that is religiously stingy with making space for anyone who is not in a car.

Woon was intimately familiar with how mindful of his safety he would need to be on Manchester. A harrowing seven-lane thoroughfare just a dozen or so blocks north of his home on Normandie - another dangerous speedway - it’s the kind of arterial that even cyclists as experienced as Woon generally avoid.

But seeing parked cars in the gutter lanes as he approached the intersection might have reassured him he would have safe passage this time.

Because of those parked cars, he would have also likely assumed* that the eastbound white Porsche Cayenne SUV in the far right lane in the distance would either turn south onto Normandie or seek to merge into one of the travel lanes well before it reached him. [*This assumes he saw the vehicle - it is hard to know from existing security footage (in another section below) if the vehicle was in the lane when he looked left or if it veered into the lane just as he was turning right.]

What he clearly did not anticipate was for the driver to be speeding 20 miles or more per hour faster than the flow of traffic. Or for her to have so little regard for the safety of the people around her, the two women riding with her, or the two-year-old toddler buckled into the car seat.

If he had, he would have paused to let her pass - he knew all too well that even his muscular frame would be no match against a multi-ton vehicle.

Instead, he positioned himself to squeeze between the parked cars just up ahead and the traffic flowing alongside him and settled into his saddle.

___

“Did you see the photos of him?” asks Ms. Beverly.

A cyclist passing by had stopped to help the fallen rider and snapped a few images of Woon’s broken and battered body to alert the cycling community to the fact that one of its own was in peril. Could anyone identify him? Did anyone know if he survived?

The only photo she had seen was of his bike, its back end snapped off, and the pool of blood about 25 feet up, hinting at how far he had flown (see diagram) and how hard his head had hit the ground.

She hadn’t wanted to see the photos, she says.

She hadn’t been able to bring herself to identify him - she asked her husband to do that. And when he woke up crying one night about how Woon had had blood coming from his ears, she was glad she had refused. She hadn’t even had the strength to see him before he was buried. She says she laid out his clothes but preferred to remember him as he was when he walked out her door for the last time.

She knew he was gone - the pain of the loss left her clutching at the ashes she wore in a locket around her neck and the laughing Buddha pendant detectives had found in the street. Officers had showed up at her door with it two days after he was killed, having deduced it was probably his. She was grateful they hadn’t booked it into evidence with the rest of the things she is still hoping to get back - his phone, his bike, his clothes, and anything else he was carrying that day.

But in some ways it still wasn’t real.

Certain sounds reminded her of the click of his bike shoes on the pavement. Certain beats might remind her of songs he used to listen to. And certain smells might trigger memories of him dancing around the kitchen.

“Nobody loved my food like Jun Woon,” she says. “That boy would dance on the side of that pot roast. He would sing to the chicken wings. He would wait for the pork chops. He would stand to the side [she imitates him eyeing up the pots]. He would check back in....Nobody enjoyed that food like my baby. And I can’t believe I won’t physically see him again. It’s hard. He was everything. He was everything. Everything.”

Knowing how much her son had been loved by his friends had been a source of some comfort. She even had had as many lockets made as she could afford so they would always have something of him with them.

The senselessness of his loss, however, remained impossible to reconcile.

In the surveillance video police released that captured his last moments, he is so alive, so strong.

She reviewed it a few times, she says, but found herself praying for a different outcome each time she watched the SUV rocket toward Woon’s back tire. The video cuts out just before the collision occurs, and it’s too heartbreaking to know that there could have been a different outcome had the driver not been in such a hurry.

“You find yourself [saying], ‘Go, Woon. Go, Woon. Go, baby; go, baby; no, no, no, no, no, no…’” her voice trails off.

While Ms. Beverly had avoided viewing the graphic images of her son as they circulated online, his friends had not.

Raw pain over the horror of those images helped propel over 100 youth into the streets the next day. They had gone to the neighborhood to rally and pay their respects to Ms. Beverly, then took over the intersection at Manchester and Normandie, to call for justice and chant, “Long Live Woon!”

What happened next was broadcast live and would quickly go viral: nineteen-year-old Alana Ealy, incensed at being inconvenienced, exchanged words with some of the cyclists, then got out of her car and punched a female cyclist before finally exiting the intersection via Normandie. A few minutes later, she circled back to Manchester in order to deliberately plow through the crowd.

![Quatrell Stallings lies on the ground after deliberately being hit by 19-year-old Alana Ealy. [Screenshot KTLA Facebook stream]](https://lede-admin.la.streetsblog.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2019/04/Screen-Shot-2019-04-05-at-9.41.31-AM.png?w=710)

Cyclist Quatrell Stallings - who was trying to help move a woman and her dog through the crosswalk to clear the roadway - was tossed into the air like a rag doll. Some of his friends tried to chase Ealy down. Others quickly rushed to his side to find he had several broken bones and that his knee was torn up.

In a city that too rarely blinks at the loss of Black life, Woon was suddenly on Angelenos’ radar.

His friends made the most of it. They held another memorial ride that drew hundreds of supporters and spoke to the media about the scourge of hit-and-runs, the dangers they face trying to get from place to place, and the need for the city to commit to protecting bicyclists like themselves.

As hundreds of riders made their way down Normandie late that Friday night, residents were relieved to see that the helicopters had woken them up for a good cause for once.

“Are you riding to protest?” people called out. “God Bless!”

Everyone in the area knew Woon, had seen him riding in the streets, or knew his family.

It was a community-level loss. And the one that they had least expected.

___

On a cool spring night in the courtyard outside Ms. Beverly’s apartment, a bright light washes over us for the second time.

It was just the cops passing by.

Again.

The police presence in the area is often oppressive. Yet residents are generally left to fend for themselves.

When Woon was jumped shortly after they moved to this apartment twelve years ago, Ms. Beverly didn’t call the police. Instead she says she confronted the gang-bangers, telling them, “This is my son. Do me a favor, can you all not jump him? Don’t rob him. Don’t take his little chain. Don’t take his little money. I’ll watch y’all back over here if y’all will help watch his back. Don’t take anything from him. Let him go to school. We gon’ be right here. This is where we live.”

They mostly left him alone after that, but she still walked to the bus stop with him and even rode with him to Henry Clay Middle School a few times before he insisted he could get back and forth on his own.

She was uneasy about letting him be too independent. He had had to switch to Henry Clay after getting gang-jumped in Inglewood and beaten pretty badly by older youth that had accused him of being from Avalon Crip (he had lived off Avalon and 51st for a time).

So she controlled what she could.

She required him to come straight home from school and check in before he went anywhere. She checked his school work and monitored his attendance like a hawk. Any time he went anywhere, he had to call to let her know where he was. When he had to drop out while recuperating from his diabetic coma, she sent him to night school so he would graduate on time. And when it came time for him to get a job, he ended up having to go all the way to Redondo Beach to work at a Vons because she wouldn’t let him work at a fast food place. She feared it would be too easy for him to get stuck there and she wanted him to set his sights higher.

As he got older, she also watched to see what colors he wore and if there was gang graffiti in his notebooks. He was a big kid, so he got hit up by older youth in the neighborhood, she says. But he was more afraid of having to explain to his mother why he was gang-banging than he was of gang-bangers.

“His friends told him his momma was mean,” she says. But she didn’t care. “He wasn’t going to fail. Not on my watch.”

Biking helped keep him square, she says. It let gang members know that he wasn’t about that life. And the more involved he got with biking, the more he became invested in the community he was building for himself. So much so that he would be in tears if he had to miss a ride with one of his crews, she laughs.

It wasn’t the perfect hobby - she recalls when he came home one day with a bent back wheel and a few hundred bucks given to him by the guy who had hit him. And it didn’t totally exempt him from everything that went on in the neighborhood, either. He was shot at just outside the front gate when he balked at handing over his phone and the rent money he was taking to a check cashing place to get a money order. But he was so dedicated to it, riding the 15 miles back and forth to work every day when he was still at Vons. It helped him manage his diabetes. It made him think about his potential greatness and about training for the Olympics. And it made him happy.

Maybe she was wrong about this nagging feeling that something might take him from her, she thought. Maybe this would keep him safe. Maybe he’d make it out OK.

Then she picked up the phone to call him a few minutes after he left her that last day and realized how wrong she was.

“I said, ‘Lemme call him and tell him how much I love him and that that was really cool what he said.’”

They were very close, but it still meant a lot to her to have him call her his queen.

“But when I called it went to voicemail,” she says. “He would never let his phone go to voicemail on me because I have anxiety really bad. Like, I’ll go to wherever you say you supposed to be because I can’t take it because of this feeling I’ve always had [that his date and time was imminent]. So he knew...he would answer to me no matter where from.”

He couldn’t answer this time.

___

When the call came this week that 24-year-old Mariah Banks would be charged almost a year to the day after causing Woon's death, Ms. Beverly says she felt a mix of relief, dread (with regard to the pain she would have to relive and fear that she could get jerked around by the justice system), and anger that it had taken this long.

She had gotten a call from someone in the community telling her Banks' sister (who had been a passenger in the car, not the driver) was responsible for Woon's death within a couple of weeks of his passing. It seemed like everyone knew, judging by the accusations flying back and forth on social media.

And yet there was no arrest.

Not confident the LAPD would do its job, Ms. Beverly even engaged in her own counterintelligence operation, showing up at a child's birthday celebration thrown by Banks' sister at the Carson salon where she braids hair. Ms. Beverly just wanted to see them, she tells me. She wanted to see if they looked like they felt any remorse or saw any of the irony in celebrating a child's life after having just taken one.

Banks only confessed to the crime when she was finally forced to turn herself in in mid-May last year. In the moment, she had apparently been sickened by what she had done and wanted to stop (possibly even pulling over to vomit), but had been convinced to flee and, later, to repair and disguise the car to cover up the crime by one of her passengers.

If the family was remorseful, however, Ms. Beverly says she saw no evidence of it at the May 5 salon party.

Or at Banks' hearing last June 8. The young woman silently stared straight ahead, never looking at her or any of the supporters that had come seeking justice for Woon.

Five hours later, when the case was kicked back to the LAPD for further investigation and Banks was sent home with no charges, a devastated Ms. Beverly chased Banks and her family out into the hallway. She just wanted answers and for Banks to acknowledge her presence - acknowledge what she had done. She even got into the elevator with Banks' mother (after Banks fled down the stairs) and got an apology, she says, but little else in the way of explanation or acknowledgement of how the family had been complicit in helping hide Banks' crime.

She was even more dumbstruck when Banks' 22-year-old cousin Rodney Richard was run down last August in Lancaster in a hit-and-run and Banks and her family posted on social media about how heartbreaking the loss was, how they couldn't understand how someone could just leave a young man in the street like that, and how they just wanted the person that hit him to come forward.

Did they not see they had done the same to Woon? To her?

It is unfortunate that a young woman like Banks with a young child could be locked up for a number of years, says Ms. Beverly, reflecting on the news that the case was moving forward. But, she argues, she herself will never be able to escape the grief that imprisons her.

"I could do [Banks'] whole sentence with her," she says, "but I will never see my son again."

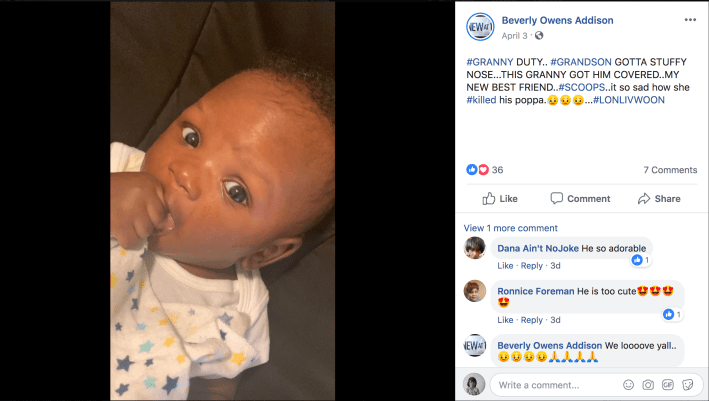

The birth of Frederick Richon Frazier III - 3 Scoops, as she has nicknamed him - to Woon's girlfriend this past December has given her some hope that her son will live on. The baby often stays with her because his mom has to work and doesn't have a lot of other help. Her Facebook feed is a running diary of every move 3 Scoops makes and the moments where he appears to take after his dad.

"He's a gracious gift, he is," she says.

Still, it pains her that Woon is not here to see him. To be there for his girl and his child as the father and family man Ms. Beverly knows he would have been.

“I cry every single day; the tears haven’t stopped,” she says, reaching for her locket again. “They’ve lessened but they haven’t stopped. And there’s moments that are unbreatheable. Every day, I just think about him. Every day. All day. Every day. All day. And I get these spells. These breathless, numb-hearted spells. Where all you can do is pray."

___

Woon's friends and family invite you to join them at events they are hosting on April 10 and April 14 aimed at honoring his memory, supporting his family, and highlighting the need for the city to take the safety of riders like Woon more seriously. The gofundme set up to help take care of 3 Scoops remains active.

For more on Woon’s case, see our previous coverage below.

- April 5, 2019: Finally: Charges Filed Against Driver that Killed Frederick "Woon" Frazier in Hit-and-Run

- July 3, 2018: Rallygoers Demanding Justice for Hit-and-Run Victim Frederick “Woon” Frazier Crash Community Meeting on Safe Streets

- June 7, 2018: LAPD Announces Arrests in Hit-and-Runs that Killed Frederick Frazier and Injured Quatrell Stallings

- May 15, 2018: Hit-and-Run Driver that Killed Frederick “Woon” Frazier Turns Herself in; Details Still Emerging

- April 18, 2018: Security Footage Shows Moments Before Frederick “Woon” Frazier Hit from Behind; Police Still Seeking Leads

- April 16, 2018: “The Car Culture that We Have Is Not Promoting Life:” Riders Gather to Remember Frederick “Woon” Frazier

- April 11, 2018: 22-year-old Killed in Hit-and-Run at Manchester/Normandie; Driver Plows Through Mourners Corking Intersection to Protest Death