The newly widened North Spring Street Viaduct recently re-opened to traffic. The $50 million bridge widening was justified as a multi-modal project to enhance pedestrian and bike safety and mobility. The new bridge is wide enough for bike lanes, but they're not there.

The Spring Street Bridge crosses the L.A. River just north of downtown Los Angeles. It connects the communities of Lincoln Heights and Chinatown. This portion of Spring Street is designated as part of the Bicycle Lane Network in L.A.'s Mobility Plan 2035. LADOT planned bike lanes there as part of a Metro Call for Projects grant to connect the L.A. River bike path into downtown L.A. The bridge connects to both sides of Lincoln Heights' Downey Recreation Center, which is currently being expanded. The bridge is also used for NELA access Los Angeles State Historic Park.

The historic Spring Street Viaduct was built in 1927, and brought up to earthquake standards in 1992. In 2006, the city's Bureau of Engineering initiated plans to widen the bridge.

This bridge widening project courted some controversy. The city's initial project scope was excessive. City engineers first planned to tear down the historic bridge to widen the roadway from about 43 feet to about 96 feet. The L.A. Conservancy intervened against bridge demolition. Though city staff presented the matter as bike-walk mobility vs. historic preservation, the L.A. County Bicycle Coalition and other bicyclists also weighed in against excessive widening, and in favor of preserving the bridge.

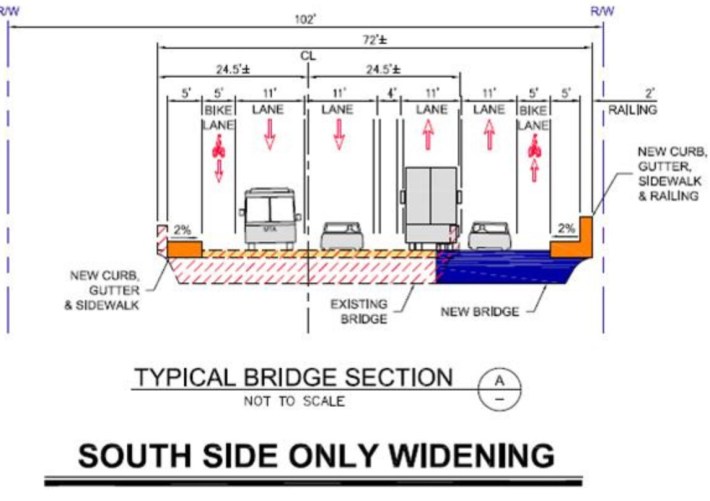

City staff went back to the drawing board and pared the width down from 96 feet to 68 feet, which meant they could preserve the existing bridge and just add a new structure extending it. The city council approved the less-destructive project scope in 2011.

The Spring Street bridge widening project was long justified as improving bike and pedestrian safety. Since a roadway widening in 1939, the bridge had been left with only one substandard sidewalk. Slower-moving cyclists ascending the bridge were forced to share narrow car lanes. The project was justified as a remedy for these deficiencies: widen the bridge deck to add a new sidewalk, widen an existing sidewalk, and add bike lanes.

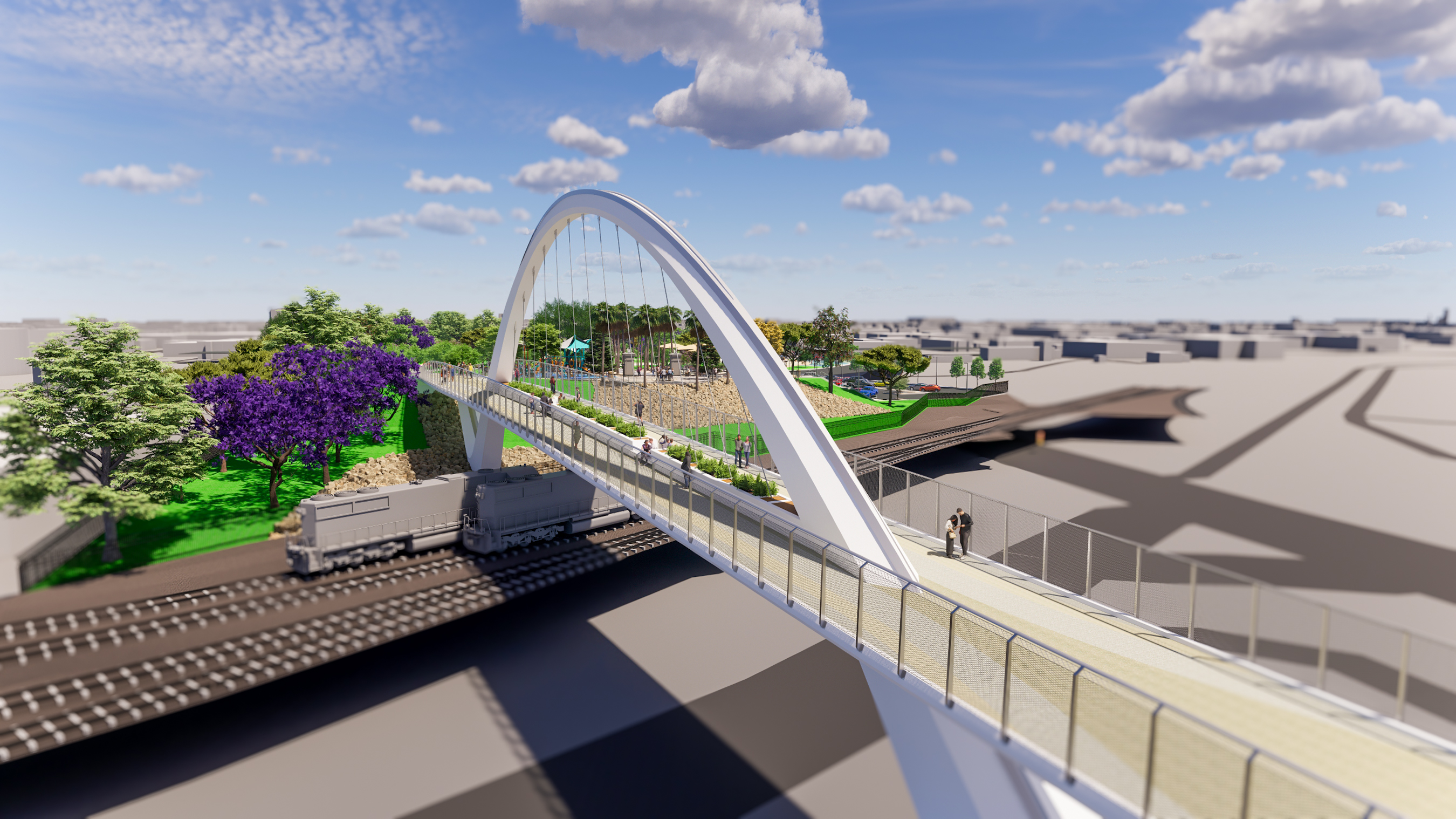

The bike lanes are shown in bridge sections diagrams and in renderings.

Rendering does not show the diagonal stripes that are on the bridge today. Image via Pleskow Architects

The project's Environmental Impact Report states a project purpose as "to improve bicycle and pedestrian circulation and safety." The project's bike lanes were specified in the city council approval in 2011.

The present striping on the bridge does not make much sense. In theory, the diagonally-striped side area appears to direct bicyclists to merge with faster-moving uphill traffic. This would, of course, be very dangerous, and would impede car traffic. In practice, cyclists are riding in the striped-off side area. Some are using the sidewalk to walk their bikes uphill, then riding them down.

It is unclear why city modified the project to omit the bike lanes.

Modification at such a late date could put the city at risk for a lawsuit - for violating the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). It is illegal for the city to study and certify one project, then construct something else. Not fulfilling the project's pledged scope might also put the bridge project's state/federal grant funding at risk.

To get further information on the bridge's missing bike lanes, Streetsblog emailed the city's Bureau of Engineering, Department of Transportation, and the office of City Councilmember Gil Cedillo. As of press time, none of them have responded to SBLA's inquiry.

Update 5 p.m. This afternoon, BOE Chief Deputy City Engineer Deborah Weintraub responded to SBLA stating:

Due to the Phase II work on the project to construct a new intersection just west of where the bridge lands heading in to downtown, which will temporarily remove the west bound bike lane and one west bound lane of traffic for approximately 6 months, the City felt it was best not to install the bike lanes at this time.

While it may be reassuring that the city may stick to the approved project scope in six months, it is still not clear why the city would, even temporarily, stripe in such a way as to direct bicyclists to merge with faster-moving uphill traffic. Nor why the eastbound bike lane would be left out based on a future westbound lane removal.