Aaron Flournoy stands on the hot asphalt in front of Lil Bill's Bike Repair shed, examining a student's bike.

As we watch him give it a test ride to see what might be wrong, she turns to me. "He keeps us rolling," she says.

That seems to be true. In the couple of hours I stood with Flournoy on the USC campus last week, where his shed stands on McClintock, near the entrance at Jefferson, a number of students stopped by to get air or a quick fix. Others just waved hello. Someone handed him a burrito over the fence for lunch.

He was clearly part of the fabric of the community.

But even with all the love and support, he said, he was really stressed out. The university had told him he and his shed needed to move off campus by the end of the month and he wasn't sure where he was going to go.

Last summer, Flournoy had taken over the shed from the previous owner who had operated the business out of the parking lot of a church on the campus. The business filled the gap left by the demolition of University Village and the loss of a student- and community-serving bike shop that was once conveniently located there.

A true people-person, Flournoy quickly became an integral part of the campus fabric - attending graduations, supporting athletic teams, serving as a guinea pig for dental students to practice on - all while continuing to fix students' flat tires.

It had been possible for him to set up on the church property because, while technically within what is considered the USC campus, the property itself had been privately owned. That changed in late 2015, when USC - after years of negotiations - finally acquired the property for itself. In late 2016, when USC finally got around to beginning work on the property, Flournoy was told to pack up his shed. He needed to be gone by late December, he was told, or he'd have to watch his shed be bulldozed.

At the eleventh hour, USC's Department of Transportation told him he could move to a spot on McClintock. Relieved, he entered into a verbal agreement with USC, began sending in $177 in rent, and set up his shop across from the Athletic Center this past January.

All was going well until about a month ago, when USC officials stopped by to tell him he'd have to leave campus for good this time at the end of April. USC has a non-compete clause with Solé, the higher-end bike shop set to go in to the $600+ million residential and retail complex about to open at Jefferson and Hoover. The fact that Flournoy's shed operation could potentially take a few repair-seeking customers from Solé (Flournoy isn't selling bikes) was apparently cause enough to get him booted from campus.

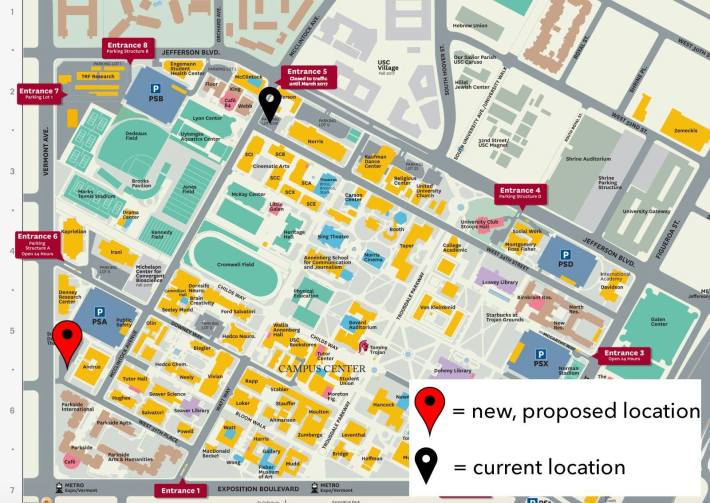

At least, that's where things stood until just a few days ago, when USC once again approached Flournoy and suggested moving him to an out-of-the-way lot on campus where maintenance workers park their electric carts.

When Flournoy called me to tell me of these latest developments last Thursday, he was clearly upset.

It was a step in the right direction to hear that the non-compete clause might have some give in it. But he couldn't believe USC was looking to stick him in an area where students never ventured. He would basically be up against one of the perimeter gates that has no opening, making it hard to access the shop from Vermont, and in an enclosed parking area, rendering him invisible to anyone on campus.

It didn't make sense to him.

Either there was some flexibility in the non-compete clause or there wasn't.

Either it was OK for him to be on campus or it wasn't.

What he didn't want was for USC to be making a show of keeping him on campus as a way to save face, all the while knowing that relegating him to an enclosed parking area would spell his doom.

He had already turned down an offer from Solé to work as a $12-an-hour mechanic in their new shop a few weeks prior, he said, because he was happy having his own business. After serving the community for several decades at his father's shop, he wanted to finally be in business for himself. And as one of two black-owned bike repair outfits in all of South Central, it was important to him to be able to keep serving the community and to be his own boss.

He wasn't sure what he was going to do, he said. But he was sure the offer of the new spot was not acceptable.

All of which might make you wonder why USC has any responsibility to him in the first place. Flournoy is not employed by the school and he's neither a student nor an alum. He's just a private business owner fighting to stay on a campus of a private college where he really hasn't been for all that long and where he technically has no real claim.

Except that it's not that simple.

Flournoy couldn't take over as the owner of his father's business on Jefferson because of the gentrification in the area - most of which has been driven by the expansion of USC's footprint.

Now that USC has made the kinds of massive investments that make it more attractive for students to live around campus and now that the Expo Line goes all the way to the beach, turnover in the area seems to have picked up its already rapid pace.

As affordability covenants expire, developers are taking advantage of the opportunity to overhaul formerly Section 8 and otherwise affordable units and market them to students. The gray building (at left, above) was one such property: 3-bedroom apartments there now rent for $3250. The building one door down is also privately owned but designated for students. And so it goes, all along the side streets around campus in ever further-reaching concentric circles.

Commercial buildings are not exempt from this phenomenon, either. Especially those that are just a few blocks from campus. Flournoy said he had heard the bike shop building was going to be torn down and turned into housing. City records seem to indicate that could be the case. Certainly the commercial building adjacent to it, at 1322, and the home that's backed up tightly against it are slated for conversion to 80 units of housing as part of a mixed-use development - it's unclear if or how Bill's building will be roped into that project.

His father had been under pressure to sell for years - he was the last holdout, Flournoy said. But when Big Bill finally retired for good at age 82, he really had had no choice but to sell. Doing so was the only real way to ensure he'd be able to live a comfortable retirement. South Central bike shops - like many small businesses in low-income areas - are not known for their high profit margins. Especially when you're largely serving folks who ride out of necessity and for whom other forms of transportation are too costly.

Flournoy understood that choice, he said, and didn't begrudge his father. And he enjoyed having his own business and having the potential for it to be a little more mobile.

But as one of so few black-owned businesses in the area, it was clear that something was also being lost.

Bill's was well-known to the South Central community and was often bustling with folks who Flournoy had been serving for years. No one was a stranger.

He was so well-known and trusted, in fact, that when one of the riders from Black Kids on Bikes (the group that rides out of Leimert Park) needed help while at the beach during the last CicLAvia, they immediately dialed Flournoy.

The riders had stumbled, ironically enough, into Solé Bikes' Venice shop looking for help. But because Solé didn't have a mechanic, they reached out to Flournoy, knowing he'd be at the event and figuring that he'd have his tools on him. Which, of course, he did.

Those are the kinds of relationships that help make communities feel like communities. And those relationships are some of the first casualties as folks begin to lose their footholds in the neighborhoods they have built their lives around.

It would be deeply unfortunate to see Flournoy displaced by USC for the second time.

As of this writing, a call placed to USC for comment last week has not been returned. Visit the facebook page students set up for him, here.