"Yea, everything [is] OK...I hope all is well with you. I'm upset right now & crying because I'm starving. Have no food."

I stared at the message on my phone. I had just checked in with 19-year-old South L.A. resident Shanique* to see how she was. I had interviewed her earlier in the summer and we had stayed in touch. Her family struggled quite a bit after the loss of her stepfather to a drive-by, the loss of her pre-teen brother to a walk-up (shooting), and being terrorized into silence by her brother's killers, who lived nearby. Her mother's disability -- incurred years earlier on the job as a postal worker -- coupled with a recent cancer diagnosis made it impossible for her to work.

And Shanique's own promising progress in school had been halted by the trauma of a rape perpetrated against her in her own home at age 14 by the friend of a cousin. When her grades began to drop, instead of being offered extra help and counseling at her high school, she had been asked to leave. She was also shunned by her cousin's family and friends and intimidated into dropping charges.

She was now struggling her way through a continuation school and working part-time at a grocery store. She was eager to find more work to help support her mother, as her hours were constantly being cut or adjusted, but this was made more difficult by a felony conviction. When Shanique's best friend had called her on the day before her 18th birthday to ask if she could pick her and another friend up, she neglected to tell Shanique that they had just attempted to break into a home. Although the police could see from the surveillance footage that Shanique had not been anywhere in the vicinity of the incident, she says, the public defender told her flat-out that he was busy with murders and didn't have time to prepare such a trivial case.

"They could have at least charged me as a juvenile!" she had fumed to me at the time.

Instead, she was stuck with three years' probation, $5000 in court fees, and a felony strike that would have made it practically impossible for them to qualify for affordable housing when their rent suddenly jumped from $500 to $1600 (when, according to Shanique, the daughter of their landlord decided she wanted access to the property).

The combination of all these things meant that money often ran out well before the end of the month.

But I guess I still hadn't expected things to be so dire.

Panicked, I immediately dialed her number.

The phone rang.

And rang.

Finally, she picked up.

Too upset to talk, she hung up almost immediately.

She texted me that she would probably go to the rec center about a mile from her house to see if she could get food from the Summer Night Lights program there -- they usually grilled hotdogs for the community. She'd done it before, she said. She'd be OK.

* * *

Shanique came to mind as I read the 7-page study on the failure of the 2008 ban on the opening of new, stand-alone fast food restaurants in South L.A. to curb obesity there and the subsequent myriad stories and think-pieces dedicated to questioning the value of the ban, pointing out that obesity appears to have risen between 2007 and 2011 (from 63% to 75% of the population), decrying the nanny state and paternalism, and wondering what made a ban seem like a good idea in the first place.

Shanique, you see, despite suffering from hunger on a pretty regular basis, is obese.

And while those writing on the ban were keen to say they saw the failure coming, including Roland Sturm (lead author of the study and senior economist at RAND), who stated, “This should not come as a surprise," there was very little deeper probing into why the failure was so predictable or into the specifics of the lives of actual South L.A. residents like Shanique.

Instead, most critiques focused on the dual challenges of understanding the food environments in low-income communities and crafting public policy that can adequately respond to them. As Sturm noted, "Most food outlets in the area are small food stores [convenience stores, liquor stores, markets, etc. where families often do much of their shopping -- not fast food places] or small restaurants with limited seating that are not affected by the policy.” By not impacting the offerings of existing fast food outlets (or the arrival of new ones in shopping centers), facilitating the arrival of healthier grocery stores or restaurants, or aiding the conversion of corner markets to offer healthier fare, the retail food landscape of South L.A. had remained relatively unchanged.

Which is not to say those lessons are not important.

Obviously, food and the availability of healthy food matters. The fact that there are few healthy markets within easy reach of people for whom transportation can be expensive (or markets that actually meet people's needs and are able to stay open) is a problem.

So is the fact that it is hard for small markets -- often where families get their staples and schoolkids get the snacks that might serve as meals on their way to and from school -- to stock their stores with healthier options. As the owner of a corner market undergoing a conversion on Vermont and 60th learned, it was much easier (and cheaper) to get Frito Lay to deliver to his store than it was for him to spend time and money running around town trying to track down specialty snacks like KIND bars or meet manufacturers' minimum purchase requirements.

But there's much more to the story. And looking beyond what people are eating with what frequency to questions of why and how may be just as important in getting a handle on the obesity crisis.

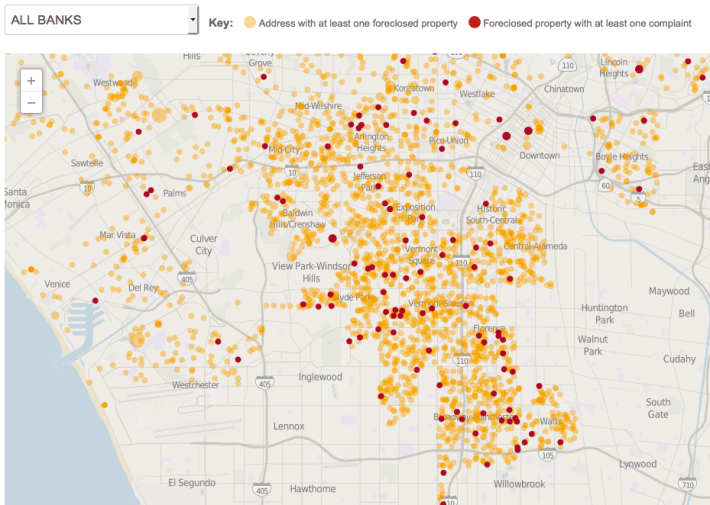

During the period framed by the study, 2007 - 2012, South L.A. was hit very hard by the recession. According to Unsheltered: A Report on Homelessness in South Los Angeles, between April and June of 2007 alone, 287 homes in the area were repossessed -- a jump of almost 800% from the same period in 2006. Things quickly went downhill from there. Homeowners and owners of rental properties alike were being foreclosed on in greater numbers than elsewhere in the city. Considering that 53% of home purchases and 42% of the mortgage loans refinanced were managed by subprime lenders (2004 data), this may not be surprising. But the loss of housing left many families in debt and scrambling for a place to live or doubling up with extended family members who often already lived in overcrowded conditions.

African-Americans and Latinos (who comprise the bulk of the area's population) were also the first to lose jobs during that period and the last to get them back. Some, including emancipated foster youth (nearly a quarter of whom live in South L.A.) and parolees (one of every five in the county resides in the area), have always struggled with both employment and stable housing. And as recently as 2012, the L.A. Times noted that, among African-Americans in areas of South L.A., unemployment and income levels rivaled those seen in the lead-up to the 1992 unrest.

And residents hadn't been doing well before the recession hit. In 2000, county-wide, South L.A. already had the highest rates of overall poverty (32%), acute poverty (15%), child poverty (40%), elderly poverty (21%), disability, persons 25 years of age and older without a high school diploma or GED (53%), renters (52%) and [home] owners (44%) who spent 30% of their income on housing, and renters (29%) and owners (21%) who spent 50% or more or their income on housing. (Data in above three paragraphs found here.)

Which is not to say there is a direct correlation between these factors and obesity. But what it does say is that there is a significant portion of the population that regularly experiences compounded stress. And multiple sources of insecurity and uncertainty for those on the margins can mean that finding the time, money, and emotional wherewithal to take care of their health is a real challenge.

Limited incomes may mean that many residents, much like Shanique and her mother, are reliant on others for access to food part of the month. They may be very aware, as a low-income patient in the diabetes program at St. John's was, that certain foods are harmful to their health. But they also know that rejecting the salt- and carbohydrate-heavy offerings of food banks means they and/or their families will have to go hungry.

For those working informally who are paid by the day or the job, not having a reliable or large enough amount of cash at one time means they may purchase food more often and in smaller quantities from small markets, vendors, or local restaurants. Planning meals and making long trips to a grocery store to buy healthier staples for their family may often be out of reach.

But poverty and lack of regular access to housing and food -- healthy or otherwise -- are far from being the only problems that contribute to poor health.

When Shanique talked to me about her health, she wasn't talking about farmers' markets, home cooking, or taking a leisurely stroll in her neighborhood for exercise. She talked about being bullied for her size, blackness, and poverty by classmates, law enforcement officers, and a co-worker at an internship. About feeling alone and like nobody cared about her or her community. About hating sitting at home alone and being inundated with sad memories, but having nowhere safe to go. About missing the brother that had been stolen from her by neighbors who couldn't leave a 12-year-old boy that wanted nothing to do with gangs alone. About the boyfriend of a relative shot biking the four blocks to his home in the middle of the afternoon. About getting caught in the crossfire between rival gang members and being too scared to move. About giving her first paycheck to a homeless family because she knew what it was like to be hungry. About her wages then being garnished for the crime she did not commit and about the gang-banging co-worker with a bad attitude who gave her a black eye as a way of teaching her about respect. About wanting so much more for herself and believing one day she would get there, but feeling like each setback was telling her not to get her hopes up too high.

I would like to say Shanique's case unique, but it unfortunately is not. While not everyone endures her specific set of struggles, too many on the margins are familiar with how easily the search for a healthier life can be complicated by a lack of access to safe and engaging recreation, a lack of access to safe park space, a lack of educational and employment opportunities, a lack of access to healthcare and health education, violence in the community, mobility issues (safe streets/safe access to transit), discrimination, and direct or indirect experiences with trauma.

The combination of some or all of these factors can contribute to stresses that put people at risk for depression, low self-esteem, violence in the home, substance abuse, and, particularly in young people, the sense that there is no point in planning for the future. These same factors -- stress, depression, lack of mobility, childhood trauma, sexual abuse -- have also all been identified as risk factors in the development or persistence of obesity.

In sum, when looking at obesity, the food environment matters -- there is no question about this. Using policy (bans and regulations, allowing urban gardening, street vendor legislation, incentives for grocery stores to move in, etc.) to engage the food environment is therefore incredibly important.

But so is the fact that residents' interaction with the food environment is not independent of how the socio-economic context impacts their ability to access food, plan meals (or plan ahead, period), or manage all aspects of their health. Meaning, it would behoove us to think more broadly about health and to learn more about how these different elements intersect if we are to craft more comprehensive and effective policy.

Regardless of their intersection, it is clear that any policy fixes aimed at a problem as multi-layered as obesity cannot stand alone. To make a tangible change in the landscape, complementary programs aimed at facilitating corner market conversions, actively engaging residents on health, and investing in the wider well-being of the community are likely needed, at the very least.

It doesn't mean the ban was a bad idea, in other words, it just means it makes no sense to expect it could ever be enough.

*Shanique's name has been changed to protect her identity.