“If it weren’t for J.P. …”

Ask any of the youth from the Los Ryderz Bike Club how they feel about the club and that is usually one of the first things to come out of their mouths.

“…Who knows what I’d be doin'.”

“…I don’t know where I’d be.”

“…He’s like a second father – the father I never had. I call him ‘Dad.’”

They're talking about the club’s founder and president, Javier “J.P.” Partida, a long-time resident of Watts whose cool and occasionally gruff exterior masks an enormous and very generous heart.

Partida will be joining other South L.A. superheroes Neelam Sharma (from Community Services Unlimited), Ben Caldwell (of the KAOS Network in Leimert Park), and Karen Mack (of arts organization L.A. Commons) to talk about the joys and the challenges of bringing food justice, urban agriculture, community arts, and recreation to South L.A. this Thursday night as part of the Visions and Voices series at USC. (Event information here.)

I had first met Partida in 2012, at the CicLAvia South L.A. Exploration Ride through Watts led by the East Side Riders (above).

Seeing how the community responded to seeing 60+ cyclists riding through his neighborhood had inspired him to think about getting youth from the community on bikes, he said when he called me a few months later. Could I come down to Watts to talk with him about launching a youth-centric club?

Oh. Hell. Yes.

Watts is packed with young people who have nowhere to go.

There are no bowling alleys, movie theaters, arcades, or safe spots in the public space where kids can just hang out and have fun with their friends. And even though the majority of the youth are not involved in gangs, the intensity of gang activity in the area constricts their movement. Parents may not even allow kids to hang out in their own front yards, wait at bus stops they feel are too exposed, or walk too far in any direction on their own. The kids that can afford their own bikes are often afraid (or not allowed) to ride alone or stray too far from home for fear of getting jacked while riding, or worse.

Given his own upbringing in that environment and the informal mentoring he was already doing with the kids that came through YO! Watts, Partida felt he couldn't get a bike club off the ground fast enough. At our first meeting, he laid out a million ideas for events, logo designs, group gatherings, and even a co-op – and he wanted it all to happen right away.

“Just get the kids out on bikes,” I remember telling him at the time. “Start with that. The rest will fall into place.”

That turned out to be very true. At first.

Despite a shaky start -- one of the group's two founding members was reluctant to participate in rides that traversed the territories of gangs he had previously beefed it with -- word of how fun participating in group bike rides could be traveled quickly.

Within weeks, the group had grown substantially. At first it was comprised primarily of young women (mobility can be less of an issue for young women than young men, as they are generally less likely to be banged on by gang members). Those riders subsequently recruited friends and classmates from the charter school on site at YO! Watts, and suddenly the group was rolling 30 and 40 youth deep.

Partida suddenly had a real club on his hands -- one that would need more than just the occasional bike ride to keep it rolling.

On top of the challenges the neighborhood presented, most of the youth came from tough home environments and/or struggled with motivation, having had to leave (or been kicked out of) at least one school prior to landing at YO! Watts.

Some were working -- often unsuccessfully -- to distance themselves from gangs or crews they had been involved in. Others were trying to stay on the straight-and-narrow after having gotten in trouble with the law. All had experienced some level of community violence, if not direct violence against themselves, family members, or close friends, from a young age and those traumas swam just under the surface for many.

So, Partida imposed structure on the club. There were rules and expectations, codes of conduct, mandatory meetings, and assigned responsibilities and titles given to every member. The club was so tightly run at one point that a few of the youth even complained that all of the structure was taking the fun out of riding bikes.

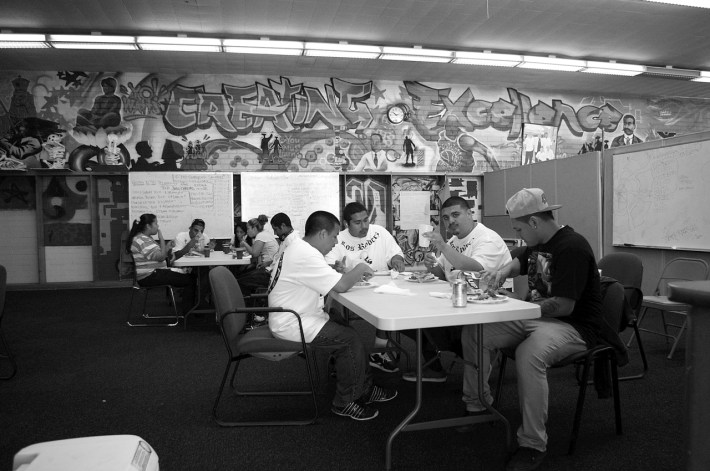

But Partida knew how little structure most of the youth had in their lives. And the discipline was instilled with love -- the riders got free custom t-shirts for every ride and broke bread together after the events (with food donated by supporter Terri Calderon), much like a family would. Partida's regular presence at YO! Watts meant the youth could stop by to relax or share their problems -- a real luxury. He was also good about recognizing the contributions the youth made to the club and the community by promoting them within the group and creating certificates to recognize their achievements.

Unaccustomed to having someone take such an interest in their welfare, youth used to ask if he got paid to run the club. He says he told them once, "My payback is seeing you guys happy, seeing you guys doing something that you love. Seeing you guys smiling out there, having fun... that lets me know that I did something right today."

The only thing he asks is that they "be grateful for everything you get and everything you get out of this."

From what I can tell, they certainly are.

All the mentoring and structure helped build trust between the members in the group so they could feel good about the personal growth they were making as individuals and as a group and, for once, safely speak to their peers about the traumas they had endured.

At a meeting I attended one night to ask them about their experience with the club, they wasted no time in describing how much it meant to them. And not just because it was fun.

Blanco, a young man on probation for drug offenses at the time, said that being able to "just go out and ride -- it makes you feel more safe [in the neighborhood]."

"Yeah, no gang violence!" chimed in Rosie, who was so thrilled with how riding had boosted her self-esteem and helped her lose weight that she was eager to recruit more women who were struggling with similar issues.

Whisper, who had begun gang-banging at age 9, said the club helped her "get off the streets, and stop fighting, gang-banging, and stuff. [Riding] takes you out of trouble...you relax and have fun times and meet new people you didn't know and see new places."

Caro said she joined because her friend Maria -- who had cried while describing how the club had encouraged her to come out of her shell -- had told her about how they participated in events that helped the community.

"Instead of getting, I want to give," Caro said of her motivation. "And I also feel freedom. When I am home, I feel like I'm locked up. Like I was in jail or something. Out in the street, I feel strong and free. It makes me strong."

As the conversation continued about how important it was to feel strong and able to resist and transcend violent experiences, I realized that almost everyone in the room was sniffling and wiping at their eyes. Freedom, safety, a sense of belonging, feeling valued, finally having the luxury to think about the future, and believing that they were setting a positive example for the community meant more to them than even they realized.

These things were not lost on Partida.

Speaking after the meeting, he reminded me of how skeptical people had been about his idea for a bike club in a neighborhood where the public space was so fraught. Hearing that pessimism had been hard, he said. But he had also remembered how hungry he had been for alternatives as a youth and how, even now, he continued to live with the consequences of the fact that there hadn't been any back then.

His plan would work. He knew it.

“By them having someone to look up to (most of the guys don’t really have that positive role model), and me growing up in the streets and being part of that group at one point of my life, I know how to relate to them. I know how to talk to them. And I know when they are bullshitting me. And when I let them know and when they see all the scars of everything that I have been through […] and what happens when you take the positive road...they see that there is hope.”

"When one of their close homies gets killed, you know," he continued, "they see. They start to open their eyes and think, 'Shit, that could've happened to me.'"

It's a thought he himself had had many times as a youth.

"When I was growing up, we had the Candyman [a friend]. He got killed by members of our same gang. For the fuck of it. There was no explanation of it. I remember his mom wouldn’t let me go to the funeral, or even go inside of the church because she said it was my fault. It was my responsibility to take care of him and I failed."

Your homies, he concluded, can sometimes be your worst enemies. Especially if you try to leave the gang.

They were certainly the ones that kept trying to drag him back down when he tried to get his life together. He didn't want any part of it -- he had a daughter on the way, he had a job, and he was tired of being on the road to nowhere. But they kept pressuring him to fight and ambushing him around the neighborhood.

That same pressure, he says, "is the reason that a lot of these youngsters don't want to get out."

Meeting the mother of his second daughter was what finally set him on the right path. In taking her son out to play football, he found himself drawn to coaching. He's been volunteering to help coach and mentor youth ever since.

Not only was it was great for the kids that he helped out, he realized, but it helped him work through his own traumas, too.

Getting up at 5 a.m. to design club logos and patches, map out routes, plan events, or fix up the club's bikes also helps to dull the demons.

"Cycling keeps me sane," he concluded. "It's what keeps me away from wanting to get high. Or to drink or smoke or whatever. That's my crack. I'm addicted to it. I'm a cycle-path."

Three years on, the club has evolved significantly.

In some ways, it has been a victim of its own success. By keeping kids on a positive track, Partida succeeded in helping them stay motivated to finish school, get their diplomas, and go on to take college courses or start new jobs. So, there are fewer of them available to ride on the weekends.

Even as their numbers have dwindled, however, Partida has continued to expand the mission. He works closely with the East Side Riders to promote black-brown unity in South L.A., supports other health-related community events, is building connections with cycling clubs around the U.S. and riding with other clubs in other communities around the county, and bringing a new generation of young riders out to events.

And his current crop of core members -- including William, Shawn, and Cheech (below) -- remain some of the most responsible and capable road captains around. [They'll be helping to lead the club's Tour de Watts next month, to which you, dear reader, are cordially invited.]

"Where I started and where I'm at," he mused, reflecting on his trajectory, "I'm proud of where we are. I don't think I would give this up for anything."

To hear Partida and other South L.A. leaders talk about their visions for their community this Thursday evening, please visit the event page and RSVP here.