California signaled its commitment to high-speed rail with a groundbreaking today in Fresno. The ceremony, featuring a speech by Governor Jerry Brown, marks the official beginning of construction on the long-awaited train.

It also puts California on track to be the first state in the nation to build high-speed rail. That depends on how you define it, though; Amtrak's Acela Express service between Boston and D.C. comes close, getting up to 150 miles per hour on some sections.

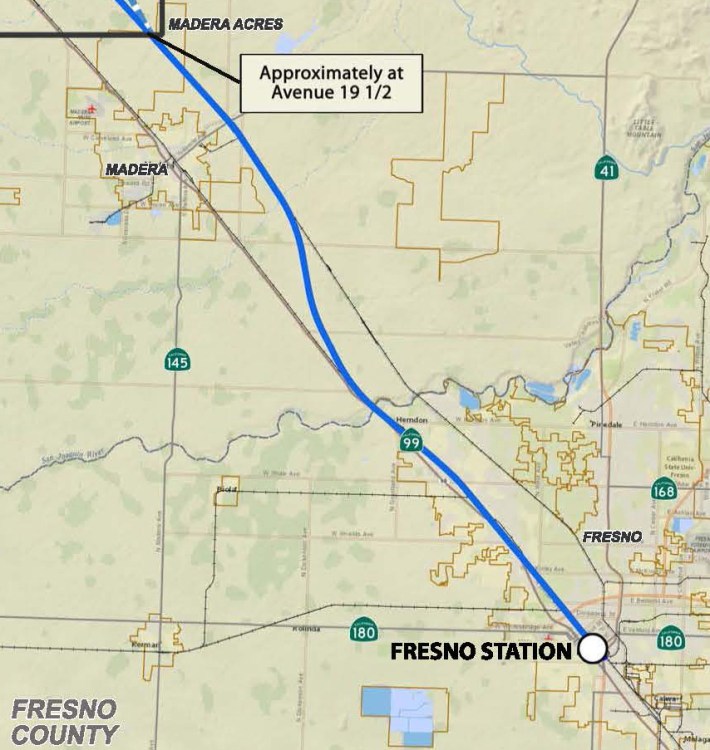

The first section of track to be constructed will run 29 miles between Fresno and the town of Madera to the north. It includes two viaducts, a trench in downtown Fresno, and twelve grade separations—most of them lifting existing roads over the at-grade tracks.

Today's groundbreaking was held at the site of the future downtown Fresno high-speed rail station. It was largely ceremonial, as actual construction may not start until April. However, pre-construction activities have been underway, including archaeological and geotechnical preparation work.

In his speech Governor Brown addressed project criticisms, saying it is necessary to be critiqued to build a better project.

“It's not about money,” he added. “You've got to get something in the ground. You've got to put the building trades people to work.”

He compared building high-speed rail with other large projects that have met with opposition, like the Central Valley Water Project, the Golden Gate Bridge, and BART. “All those projects were a little bit touch-and-go,” he said.

Despite the joyful faces and rousing speeches, it will be many years before anyone gets to ride high-speed rail in California. The next two construction phases will extend the rail line south towards Kern County, but will not reach as far as Bakersfield. A contract for the second construction phase should be signed in the next few weeks, but other construction work is still in planning stages.

Brown acknowledged the prolonged project timeline. “I'm setting these goals now for 2030, and I'm doing everything I can to make sure we get there.”

“If it seems a long time to you,” Brown said to the college students lined up behind him, “I'll be 92 in 2030. I'm working out, I'm eating my vegetables. I want to be around to see this.”

He also acknowledged the current multi-billion-dollar gap in funding needed to complete the project. “I'm not sure where the hell we're going to get the rest of the money,” he joked. “But don't worry, we're going to get it.”

Funding isn't the only issue holding back the project. Routes are still in contention, land needs to be acquired, and several lawsuits are pending.

In December, a federal panel of the Surface Transportation Board ruled that its previous approval of the Fresno to Bakersfield segment preempts California's Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Several lawsuits against the project were relying on CEQA. One of those lawsuits, with the city of Bakersfield, was settled a few days after the federal ruling [PDF], with both parties agreeing to work together to find a locally preferred route but with the state agency retaining sole authority over deciding on the alignment.

Meanwhile, future system stations are being prepared in Anaheim and San Francisco. The Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center (ARTIC), with a super-cool roof, was recently completed [PDF]. San Francisco's Transbay Terminal, still under construction, is a several-blocks-long building that will incorporate a large space underneath in anticipation of the future arrival of the high-speed train.

Maybe Brown shouldn't have compared the high speed rail project to building the great cathedrals of Europe. Those took many generations to complete, and, as he pointed out, the workers who carried bricks for them didn't live to see completion.

But his point was that this is a project with the potential to transform California for years to come.

“We are rooted in our forebears, and linked to our descendants,” he said. “This is truly a California project bringing us together today.”