In a last-minute maneuver before the California Legislature's summer recess, Assemblymember Henry Perea (D-Fresno) amended a bill to delay the application of California's cap-and-trade system to fuels until 2018.

Co-authors of the bill, A.B. 69, include Assemblymembers Cheryl Brown (D-Fontana), Tom Daly (D-Anaheim), Isadore Hall (D-Rancho Dominguez), Roger Hernandez (D-West Covina), Freddie Rodriguez (D-Chino), and Rudy Salas (D-Bakersfield), as well as Senators Lou Correa (D-Santa Ana) and Norma Torres (D-Chino).

California's cap-and-trade system is intended to encourage businesses to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) by placing a cap on the total GHG they may produce, and then allowing them to buy or sell emission credits, depending on their ability to meet the cap. It is being phased in over time, and until now has only been applied to manufacturing enterprises. The cap is scheduled to apply to the production and transport of transportation fuels starting in January 2015. Perea's bill would delay that for three years.

Perea recently joined fifteen other assemblymembers in signing a letter to the California Air Resources Board asking CEO Mary Nichols to redesign the cap-and-trade system to spare drivers the consequences of “an immediate jump in gas prices at the pump,” which the letter claimed would come on January 2015.

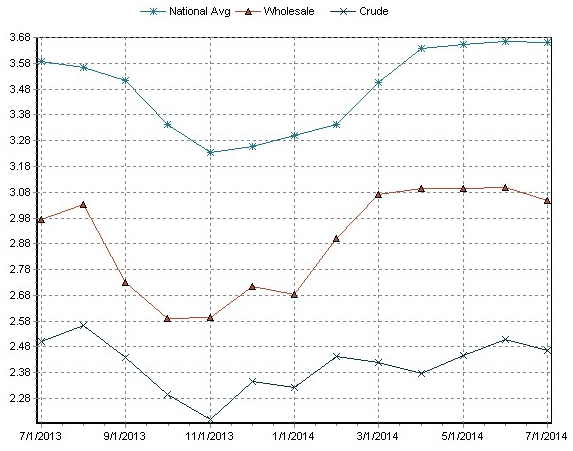

Costs associated with the cap-and-trade will most likely be passed on to consumers, but the timing and amounts of those increases are not certain. Estimates of the program's effect on the price of gas vary from 10 to 20 cents per gallon. That's far less than spikes in gas prices seen a few years ago, and about the same amount by which the price of gas fluctuated throughout California in the last year, according to the AAA. In other words, this "jump in price" wouldn't be beyond what California drivers have already dealt with.

Of course, the whole point of cap-and-trade is to provide a “market mechanism” to encourage people to cut GHG emissions. Making people pay for their contribution to climate change will encourage them to find ways to reduce their emissions. If it doesn't hurt, it won't work.

And revenues raised from cap and trade, estimated to be at least $2 billion annually, will be used to improve transit options and build housing near transit, providing better alternatives to driving.

Perea's concern, says his staff, is for low-income workers who live in areas with little transit and few alternatives to driving long distances to work. He hopes that by delaying the program for several years, it will give everyone time to adjust to the coming increase in prices.

Low-income workers do suffer disproportionately from car dependency. A recent report from the New American Foundation [PDF] detailed the backward incentives of an economy that puts a premium on fuel-efficient vehicles, leaving only older, gas-guzzling, polluting vehicles within reach of those who are barely scraping by. People who don't make much money often can't take advantage of incentives to buy electric vehicles, and many have to travel long distances to find low-paying jobs in areas with limited transit options. Thus they spend a higher percentage of their income on driving, and their long commutes in old cars contribute to poor air quality in their regions, adding to already high health costs.

But how much will a delay in cap-and-trade for fuels actually benefit low-income residents? Ryan Wiggins of TransForm pointed out that for the average Californian, who uses 40 gallons of gas per month for transportation, including indirect reliance on fuels used for goods and services, a 20-cent increase comes to about $8 per month -- chump change in the realm of gas costs and the price fluctuations that happen anyway.

Meanwhile, other entities--like oil companies--stand to benefit far more from Perea's bill than the average Californian at any income level.