Given all the coverage and advisories about Los Angeles receiving heavy rains today, Streetsblog is kicking off an occasional series that makes the connections between rain, streets, creeks and people.

There's an oft-repeated phrase that emerged during the 1970s Feminist Movements that states "A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle." It's credited to Irnia Dunn, and appears on posters, T-shirts, and even in a U2 song. Overall it's a great quote for rethinking women's independence and agency.

It appears that when trying to imagine two entirely unconnected things, Dunn perhaps seemed to think that there just weren't any connections between fish and bicycles. Certainly fish can't ride bikes.

Streetsblog asserts that fish do need bicycles.

Fish need pedestrians too.

And transit.

Also complete streets, parking reform, freeway removal, and pretty much the whole livability agenda that Streetsblog is known for.

What's the problem?

Streetsblog readers are familiar with the most obvious problems inherent in the present car-heavy transportation system. Cars kill lots of people. They cause air pollution, including greenhouse gases. In addition to health problems from toxic air, over-reliance on cars makes for a sedentary lifestyle, leading to obesity and chronic disease. That's a short summary, leaving a lot out.

What may be somewhat less intuitive is that cars are also a primary cause of water pollution.

Cars and their drivers cause a lot of the water pollution directly. Many pollutants from cars settle onto roadways. Rain carries them into storm drains, creeks, rivers and the ocean. Every time a driver presses the brake, brake pads shed a small amount of copper. All this copper (along with some copper from some other sources) finds its way into local rivers which are officially impaired by copper – meaning there’s a little too much copper to be healthy for fish and other aquatic life. Similar water pollution attributable to automobiles includes oil, transmission fluid, brake fluid, antifreeze, etc. It’s basically all the gunk that makes those spots on ground in parking spaces. Rain carries those spots into creeks and rivers.

On top of the pollution that cars contribute directly, there's also a huge indirect impact. Los Angeles can't have millions of cars without the huge expanses of asphalt and concrete surfaces needed to support them. This includes freeways, ramps, streets, driveways, and parking lot after parking lot.

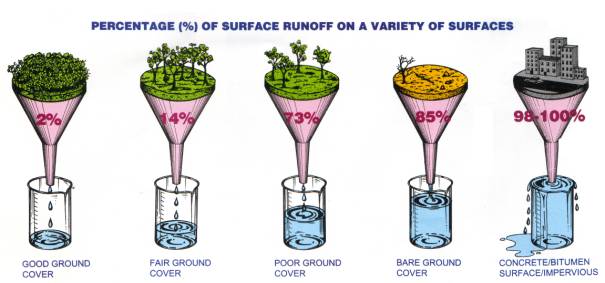

Unpaved surfaces act more-or-less like sponges, soaking up significant amounts of rain that falls on them. When cities pave the basins (the watersheds) that drain into rivers and creeks, more water runs off more quickly. The increased volume of runoff water leads to higher flows of water in waterways. This causes erosion and flooding. Risk of flooding leads to lining rivers with concrete. Concrete doesn't make for great fish habitat.

Rainwater in Los Angeles can fall on a concrete driveway, flow along a street's concrete gutter, then into a concrete storm drain, and into a concrete river. All along the way it's picking up pollution.

Car-centric cities produce rivers and creeks that are unhealthy for fish and for humans.

What's the solution?

Generally it's really important to reduce pollution at the source. A whole lot fewer cars would do the trick. But in the meantime...

Rainwater harvesting expert Brad Lancaster (one of the contributors to L.A. County's Model Design Manual for Living Streets) has a great way to describe the solutions. Healthy cities need to treat rainwater as a valued guest. Instead of ushering runoff water away as quickly as possible, invite it to not be in such a hurry. Hey raindrop! What's your rush? Slow down and stay a while. When water flows more slowly, pollutants drop out, flooding diminishes, and neighborhoods turn greener. Plants and soil act as a natural filter, breaking down many pollutants and rendering them harmless.

Instead of the concrete-concrete-concrete runoff trajectory, cities can be retrofitted so runoff water flows over natural areas. The street right-of-way is the ubiquitous real estate where this can take place.

There are a number of good examples of local street retrofit projects, often called "green streets," that slow down runoff. For this article, Streetsblog will highlight just one recent example.

The Woodman Avenue Multi-Beneficial Stormwater Capture Project opened earlier this month and has been receiving its first big dousing this morning. The project is located in Panorama City, a Los Angeles City neighborhood in the center of the San Fernando Valley. The Woodman project extends about three-quarters of a mile on the west side of Woodman Avenue from Lanark Street to Saticoy Street in Panorama City.

Before its retrofit, this stretch of Woodman featured an uninviting impermeable concrete median with a single row of magnolia trees.

The City of Los Angeles (Department of Water and Power and Bureaus of Street Services and Sanitation) and The River Project worked with the community to redesign the median.

Median asphalt was removed and replaced by a decomposed granite walk path alongside a gently sloped landscaped trough, called a swale. The swale was planted with drought-tolerant native shrubs. The magnolia trees were replaced with native sycamores.

Concrete gutters were opened to redirect rainwater from the street into the landscape.

The project also improved bus stop seating.

In addition to what's visible on the surface, there's an underground detention system - basically a big leaky box that collects rainwater and allows it to soak back into the earth. The median now captures rainwater runoff from a surrounding area of approximately 120 acres. In an average rain year, it is expect to infiltrate 75-80 acre-feet (about 25 million gallons) of water.

This week's rains have saturated the site so much that the decomposed granite path feels like a wet sponge. The flows from the current rain were so heavy as to undermine small portions of the walk path.

As its name suggests, Woodman's "green street" retrofit provides multiple benefits. Water pollution is filtered by the vegetation. Slowing the water down means lessened flood risk in the nearby Tujunga Wash, a tributary of the L.A. River. Soaking water into the ground increases the water supply locally. Green space contributes to cleaner air, and a better quality of life for humans. And fish, too. These green infrastructure benefits gradually improve over time as vegetation becomes more established.

If Los Angeles continues into a car-centric future of ever-widening roadways, the problems associated with driving continue to be magnified. If Los Angeles' future is multi-modal, with cars taking their lessened role, alongside increased transit riding, walking and bicycling, then local streets can shrink, making space for greener neighborhoods and healthy waterways.

(This is the first post in a multi-part series inspired by this three-part series published by SF Streetsblog in 2010, which is still recommended reading: Part 1 - Daylighting Bay Area creeks, Part 2 - Creeks below SF streets , Part 3 - What SF can learn from other cities. It's linked above, but I'd like to draw attention to the Victoria Transport Policy Institute's detailed report Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis II – Water Pollution which provides a more technical analysis of these issues. Some of the material for this post is adapted from my 2009 L.A. Creek Freak post Why I Creek Freak Like Bike.)