Flanked by industry or warehouses on either side for much of its trajectory, and running parallel to defunct and unkempt railroad tracks that are liberally adorned with debris, graffiti, and enormous mud puddles when it rains, the Slauson Avenue corridor doesn't seem like the most human-friendly place.

And, if you've ever felt reckless enough to ride the street on your bike, you would probably attest to that observation. There is no shoulder, traffic moves fast, regardless of the time of day, and on the north side (along the tracks), the road can be rough on your tires and quite dark at night.

Empty and desolate as it may appear to be, however, Slauson actually slashes its way through a series of neighborhoods that are chock full of families. You just don't see much evidence of them thanks to the 30,000+ cars, buses, and trucks that rumble through there daily, lack of mid-block crossings and other pedestrian infrastructure, poor lighting, graffiti, and general filthiness of the corridor. The unhealthy and unsafe conditions serve as yet one more strike against community cohesiveness by discouraging residents from being out and about in their neighborhoods.

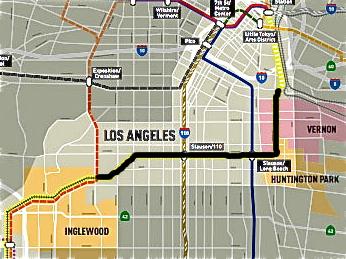

So, it is incredibly exciting to know that plans are slowly moving forward on the proposal of County Supervisors Mark Ridley-Thomas and Gloria Molina to convert the 8.3 mile corridor between Huntington Park and Crenshaw into an active transportation corridor.

Not just because transforming the right-of-way along the tracks into bike and pedestrian paths would make passage safer for the thousands of people who want to connect to transit in the area (i.e. the Vermont/Slauson stops see more than 3700 boardings per day).

But because, if built with the surrounding community in mind, it could be a tremendous boon to those who must traverse the corridor on a regular basis and who have few safe and welcoming recreational spaces available to them.

With those aspirations in mind, I attended the first public briefing announcing Metro's feasibility study for the project last Thursday.

I came away with somewhat mixed feelings.

As of now, the focus seems to be on creating bike and pedestrian paths for people passing through the area who are looking to make transit connections or traverse some distance to get to specific destinations. It doesn't mean locals couldn't use the space, of course, but it isn't currently being conceptualized as a place where they might be able to gather to relax.

There are a few reasons for that.

Because the space along the corridor is a Metro-owned right-of-way and funding would likely come from Metro, a representative explained to me, the project would have to tie back to transportation.

Exercise equipment or more recreational-type amenities along the right of way -- things that community would love to have -- would fall outside of that mandate.

And, there isn't a ton of space available to be converted.

Metro can't yank up the tracks or pave over them if there is the possibility that they might be used for train transport at some point in the future. And, despite the fact that the tracks haven't been used in years, it wasn't all that long ago that Metro was considering using them to connect LA with the South Bay.

Which means that project planners must work around the tracks to find the most effective way to help facilitate the non-motorized movement of people within a long but rather narrow space (for more on the original proposal for the feasibility study, click here).

While I fully understand these constraints, part of the feasibility of a project like this involves demand modeling for bikes and peds. And, in my mind, at least, building an active transportation corridor and getting people to use it are often two very separate things.

Anyone who has followed our coverage of South L.A. knows that the Field of Dreams approach -- build it and they will come -- does not always work that well there. All the bike lanes or pedestrian-friendly infrastructure in the world won't convince people -- especially youth or the parents of younger kids -- that it is safe to walk or ride if they believe that they or their kids are likely to be hassled, have their bikes jacked, or worse.

It doesn't mean that the neighborhoods of the area are terrible, unsafe places. On the contrary, the people I know in the area are incredibly warm and welcoming.

But the prevalence of gang activity in many of the neighborhoods along the corridor has impacted people's perceptions of safety and, consequently, their mobility habits. Residents do not feel able to see their streets as potential sites of recreation. Several have told me they get on buses and travel to other neighborhoods just to walk in a park because strolling around their own neighborhood doesn't strike them as a viable option.

Understanding how perceptions of safety constrain mobility and finding ways to mitigate those concerns through programming, partnerships, and amenities will help make the corridor more inviting to the community.

The safer everyone feels, the more people from the community will be drawn to the paths. The more actively the community embraces the paths, the stronger and healthier they will be, the safer they and people passing through will be, and the more successful the project will be.

Win-win, right?

Accommodating the community might not be as hard or complicated as it sounds.

One way to draw them in might entail creating space for vendors in some of the wider stretches of the corridor, at intersections (which sometimes have more space), vacant lots, or straddling the tracks (if some temporary and non-destructive covering could be created where they could set up).

The vendors set up between Central and Broadway that I have spoken with have all been at their sites every weekend for years. Most live just up the street from Slauson, are family-run operations, and have built up a regular base of clientele comprised of local families and people passing through the area on business.

A man who sells vacuum cleaners and miscellaneous household repair items said he had moved between his regular spot on Main St. and Normandie a few times, but he had been along Slauson for a total of thirty years.

Eyeing up the graffiti from a set of the Rollin' 50s on the wall beside him, I asked if he'd ever had any trouble with gangs or been asked to pay taxes to them.

No, he laughed (in Spanish). They leave me alone. And when they've tried to get payment, I've told them 'no.' I have a license to vend. The only people I pay taxes to are the federal government.

Another young man who had taken over the stand while his uncle napped had been working along Slauson for three years.

My conversation with him was the first he'd heard of the project, and he was concerned that that meant that the vendors were likely to be unceremoniously pushed out.

At the same time, he sounded super-excited thinking about the potential transformation of the space. He had gone to Augustus Hawkins High School, at 60th and Hoover (just south of Slauson), and he said students there were hungry for ways to get involved in community projects and help make their neighborhoods better places.

He couldn't wait to tell them about it, he said.

Then he looked at me for affirmation that they would be included in the project.

"I think it would be great if they were involved..." I said, unable to promise more.

Which brings me to a second suggestion.

It would indeed be fantastic if Metro and planners were able to engage students and their families on envisioning the possibilities for a transformed corridor. It wouldn't be easy, given that there are as many as 20 schools to be found on either side of the tracks between Central and Crenshaw. But it isn't impossible, either.

The LACBC and TRUST South L.A., for example, are already running an Active Streets program in the area and working with school administrators and parents to organize around issues of livable streets in the community. At their most recent event at Budlong Elementary (a few blocks south of Slauson), parents spoke of how thrilled they were to have an opportunity to safely exercise with their kids and other families. It clearly wasn't something the parents felt they could do on their own. But, given the opportunity to do it as part of an organized group, they jumped at the chance and some requested that more such events be planned.

Cobbling together an advisory committee of youth representatives from the various schools and engaging them on ways to play a supporting role in the project -- mapping safe routes to school, creating public art for the stretch or trail near their respective schools, brainstorming programming for how the space can be used (nature walks for families, group bike rides, or walking school buses), or getting their perspective on what would make them feel like the paths were safe enough for them to use -- could be beneficial to all involved. Not only would it help students and parents feel that the project was intended to benefit them, it might give them a sense of ownership over it, thereby giving them a greater stake in ensuring it is a safe place for all to enjoy.

The two major health centers that are found along Slauson -- St. John's (at 58th and Hoover) and Hubert H. Humphrey (at Main and Slauson) -- may also be potential resources.

A diabetes class I've been following at St. John's, for example, gets their exercise picking up trash and watering the garden boxes the clinic installed in the parkways along 58th St. In the process, the patients have gotten to know the neighbors they need to borrow water from for the plants. This has helped to build community in an area where neighbors can be wary of each other. And, it also has also helped nourish a community that has limited access to fresh food, as anyone is free to take the produce.

Working with health professionals to create space for similar garden programs, the installation of fitness equipment, a farmer's market/produce stand, or other health-focused activities along the path could benefit the patients lacking park access and healthy food options while ensuring a more regular presence of stakeholders.

To their credit, the Metro representatives I spoke with at the briefing were kind enough to listen to me sputter on and on about the importance of involving the community in the project.

They reminded me that this was just the beginning of the process -- at present, they were just trying to determine the extent to which the project was feasible. There were no funds for the project as yet and funds for the kinds of things I was looking for would likely have to come through partnerships.

All of which makes sense.

But I think, too, that if you don't begin with a better understanding of the host community and its needs from the outset, the project will suffer for it down the road. And, things that might not be seen as active transportation elements per se (i.e. exercise equipment) may be essential in preparing or encouraging people to attempt to make more of their connections by walking or biking.

Plus, it's the right thing to do. The area, like much of South L.A., is intensely park-poor and was once a neglected black enclave, as racially restrictive covenants kept blacks from being able to own property outside of the Main-Slauson-Alameda-Washington box. It hasn't really seen a whole lot of investment since. It's about time that changed.

Best of all, exploring the potential of local partnerships and planning accommodations for the community now will help make the corridor safer and more welcoming for all users in the long run. And that kind of sounds like a key component of feasibility to me.