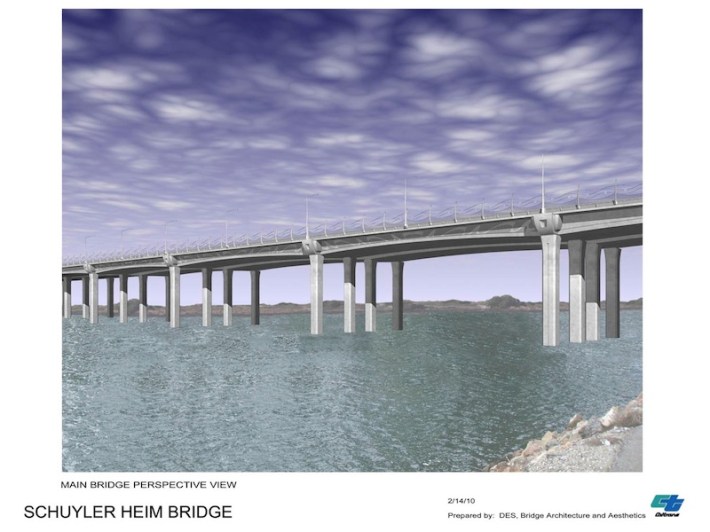

The massive Gerald Desmond Bridge replacement project—y'know, that pocket-change $1B, 1.5 mile roadway project that will sit perched above the Long Beach Harbor—has shadowed a smaller bridge project on Terminal Island: the Heim Bridge replacement project.

The Commodore Schuyler F. Heim Bridge, a vertical-lift bridge that opened in 1948, spans over the Cerritos Channel in the inner harbor and acts as a major arterial between West Long Beach and Terminal Island. It is used by both trucks entering and leaving the Port on the north side of the island—the only north-south access to the island—but also by the many Port workers who live on the west side in addition to the more well-known Vincent Thomas Bridge to the west and the Gerald Desmond Bridge to the east.

So why, oh why, are there not any pedestrian or biking elements on the new span, being built to the east of the currently dilapidated Heim Bridge?

Historically, the bridge, initially owned by the Navy and named after Commodore Schuyler F. Heim, the commanding officer of the Terminal Island Naval Base throughout World War II, began to show signs of settlement just three years after being built. This was largely due to the oil extraction occurring in Long Beach Harbor, prompting the city to pump water into depleted oil field beneath the harbor in hopes mitigating the settling.

"By the end of the decade, the shifting terrain beneath the bridge foundations had caused cracks in the reinforced concrete pillars beneath the bridge, requiring additional repairs," said Judy Gish of Cal Trans. "Throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, bridge repairs continued for routine maintenance, as well as for damage caused by trucks and marine vessels."

Come 1974, was bridge was handed to the City of Long Beach by the Navy.

In this sense, it is understandable as to why the original bridge lacked such elements: it wasn't initially intended for public use. But repeated issues pointed towards the fact that these elements could have been considered.

With the 1987 Whitter Narrows earthquake, a $2M refurbishment of a tower girder that twisted during the shake was done; no conversation about possible pedestrian or bicycle elements was discussed.

In 1994, the Northridge earthquake determined the bridge was in dire need of seismic retrofit improvements, prompting Cal Trans to discover that replacing the bridge would be more cost-effective than retrofitting (a common discovery for public projects nowadays, it seems).

In October of 2011, the $210M (you read that right) replacement project started—and yet again, not a single conversation about a possible pedestrian and bicycling elements are included.

"In addition to creating a new fixed-span bridge that meets current seismic standards, the project also adds 42 feet in width in the form of standard shoulders and a southbound auxiliary lane," Gish said. "The design will accommodate three 12 foot wide lanes, and 10 foot wide shoulders in the northbound direction. There will be three 12 foot wide lanes, a 12 foot wide auxiliary lane, and 10 foot wide shoulders in the southbound direction. The minimum vertical clearance of the bridge will be 46.9 feet over the mean high water level, allowing for accommodation of the new 45-foot fireboats."

Glad to know all those cars and trucks and boats were so deeply considered in this replacement project. When asked—twice—about the lack of pedestrian and bicycle elements, Cal Trans remained mum. Perhaps they don't want people or bicyclists being too near the toxic sites of the proposed SCIG or expanded ICTF projects up the way a few miles (we can all imagine the beautiful bike ride West Siders would have with that one on their way to work at the Port). Or perhaps they just don't want people accessing Terminal Island via foot or bike—even with the Port encouraging such modes of transportation.

The bridge, set over the course of six phases, is expected for completion (for trucks and cars) in 2017.