"It's still important for us to come together," began Taryn Randle, one of the ride leaders and member of both the Ovarian Psycos and Black Kids on Bikes.

The black-brown tension sometimes present in L.A. had been a surprise to her when she arrived here from Chicago, she told the largely black and brown crowd. Fixing it had become a major focus of her studies and work, and she looked at the Black & Brown Unity Ride (organized by the Psycos, BKoB, and the East Side Riders) as a simple but effective way to take the issue on.

"It doesn't make sense for us to have this unstated hatred towards each other based off of ignorance. I think it can be overcome by simple things like this -- us coming out like this on a Sunday, biking, kicking it, eating, listening to music....It's a good way to start that conversation and building that bridge."

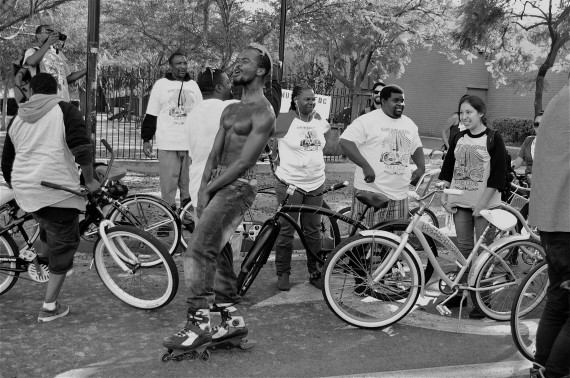

Bringing groups of riders together and letting the communities they rolled through see that adults of all races could have fun together, she and others felt, could provide a good example for communities and youth struggling with those issues in their own neighborhoods.

Along the way, Taryn reminded the riders that the purpose of the ride was unity. She encouraged them to talk to the riders they hadn't come with so that they could get to know each others' experiences.

The openness of riders to learning about each other seemed to make it easier for people to join in as we went along.

At Mariachi Plaza, one of the start points of the ride, I spotted a Latino gentleman on a bike watching the riders stretch. I asked if he wanted to come along with us.

Let me call my son, he said in Spanish.

He wanted his fourteen-year old to see the spectacle and join in. When his son said he couldn't get there in time, the man decided to come along anyways. It was his first experience with a group ride, and he appreciated the larger purpose behind it.

At Exposition Park, we picked up a rollerblader with an iguana on his head. He was originally headed to Venice, but said there was no way he could miss out on rolling with us.

As we headed into South L.A., pedestrians stopped and waved, asking what we were riding for.

Replies of "Black and brown unity!" would often inspire a "God bless you!" in return. Especially around the churches, many of which were either just beginning services or just letting out as we rolled past.

Once at the WLCAC, riders broke bread and began to talk about what the ride had really been about.

A number of riders spoke about their confusion about why tensions between the communities existed and their hope that genuine gestures, like the one they had made today, would open a new path to reconciliation between groups.

In addition to concerns about bettering relations between communities of color, talk turned to an issue both communities have in common -- incidences of police brutality and the criminalization of youth of color. Part of the mission of the ride had been to raise awareness about the rally and march being held Monday (today) in downtown L.A.

One woman talked about how her young cousin's call to 911 when his parents began a verbal fight morphed into a brutal physical altercation when police arrived. While domestic dispute calls can be some of the most unpredictable and, therefore, dangerous calls police deal with, the excessive force, racial epithets, and insults her family endured appeared to be well outside of police protocol for such incidents. The tasering of her 16-year old cousin in response to his question about what the officers were doing and the blow to the back of the neck of the 10-year old child, panicked and hugging his tasered brother on the ground, traumatized the family. The woman's tasered cousin was arrested and put in juvenile hall for reasons they are still unsure of, she said. The case has been back and forth in the courts for months, but there has been no resolution.

She wanted people to be aware these things happened to good people, she said, so that we could take a stand together against it.

For me, the ride was unique in the willingness of the riders to openly acknowledge and address an issue that is well-known to people within those communities but often downplayed for outsiders. Many residents within communities like South L.A. are tired of fighting the negative stereotypes about who they are and what happens in their neighborhoods. They want to see positive stories coming out, not stories that play into or appear to confirm the narratives others have constructed about them.

While that is entirely understandable, it makes it hard for anyone -- insider or outsider -- to take on an issue a community does not want to acknowledge.

Admirably, these riders opted to speak the problem's name and tackle it together.

The only questions that remain are figuring out "what black and brown unity means to [people]," as a speaker put it, and what serves the cause best -- dialogue or action?

For these riders, both are important, but the activities of the day seemed to suggest the power lies in action.

"I don't think about skin color when I'm on the bike," said one man, calling the bike a great equalizing tool. Anyone can ride one, and all that matters is that you be willing to roll.

An African-American man grabbed the microphone to make his statement about what unity means. He pointed at his Latina wife and mixed-race child.

"That's my baby, and that's my 15-year old [son]."

He grinned. Everyone hooted and applauded.

Enough said.