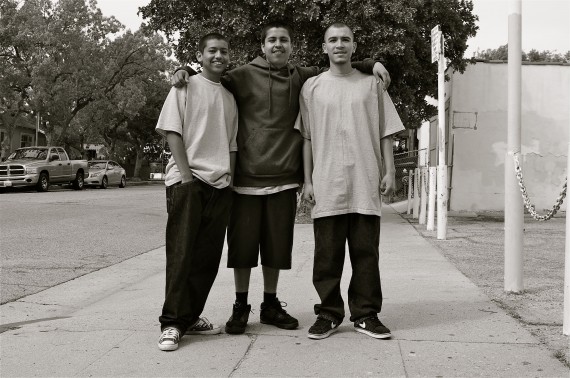

Mikey, Jonathan, and George were waiting for a friend just a few feet from the corner of Ave. 50 and York Blvd. in Highland Park when a police car pulled up. Two cops got out and told them to turn around, spread their legs, and put their hands behind their backs.

The police proceeded to give them a very thorough pat-down, including reaching their hands into the boys' pants and turning their pockets inside out. They rifled through the boys' wallets for ID and then ran their information. They poked around in the truck the boys had been standing next to, even though it wasn't theirs.

The boys were clean -- something the kids had told the police themselves, to no avail. Without an apology or even a "Have a nice day," the police were gone. The whole incident had taken only a few minutes.

"What was that all about?" I asked.

The police had been looking for weapons, they said. It happens to them a lot. It happens to all their friends, too.

It was normal, they shrugged.

While it might be the "norm," it shouldn't be "normal" for minority and lower/lower-middle class youth to feel they could be treated to public TSA-style pat-downs any and every time they strike out into their neighborhood streets. Besides being unlawful, such incidents are demoralizing, dehumanizing, and disempowering. Because these incidents generally happen in view of everyone, they also have the unfortunate effect of communicating to the more recent arrivals that the minority youth are trouble, while effectively telling these youth that they are not welcome in the very neighborhoods they grew up in.

Livable Streets Should Be Livable for All

Strikingly, the incident happened just across the street from the bike corral in front of Café de Leche. The corral -- the first in the city -- was a gesture meant to signify that the community welcomed cyclists and hoped they would ride up, lock up, and explore all that the community had to offer by foot. Similarly, the pedestrian crosswalk in the heart of the business district of York Blvd. was put in place to make the streets friendlier and more inviting to those hoofing it about.

Given what I witnessed and how frequently stops like that occur, the question is, "Are the streets equally welcoming to everyone?"

How can we reconcile an enhanced pedestrian experience for some with the fact that others might feel more under surveillance? Or greater access for bikes more generally, but no real improvement for minority youth on BMXs, who complain of being stopped because the police assume that they use the bikes to commit crimes?

Infrastructure designed to make communities more livable is a great first step, but it often isn't enough to bridge some of these deeper socio-economic gaps. Is there some way in which we can use infrastructure as a platform from which to build better bridges between long-time residents and newer arrivals?

Questions about the value of and potential opportunities created by infrastructure are particularly salient in places such as South L.A., where the issue is not gentrification, but that streets can be quite hostile to the people, and especially the male youth, that live there.

Over the past couple of months, I've been slowly exploring issues such as racial profiling, gang violence, prostitution, and displacement in South L.A. to try to pin down their impact on how people use their streets and the extent to which they feel connected to and invested in them. Although these issues are not always part of the livable streets conversation, the reality is that all the infrastructure in the world can only do so much if the people do not feel that they can take advantage of it, that it is relevant to their needs or aspirations, or even that the efforts to better the community represent a sincere investment.

In the coming weeks, I'll be posting stories from the perspectives of residents to illustrate the links between these issues and the livability of streets. I'll also be looking at some of the local organizations that have come up with innovative ways to address these issues in all their complexity as a way to gather a set of best practices. Up next week: the story of a young man who started running with crews in elementary school, first to protect himself from harassment and, later, to help protect his friends from violence. Being part of a crew made his world much smaller -- there were suddenly even fewer places he could go safely. And it still affects his movement around the streets now, even though he left the crew behind over a year ago.

**While this piece highlights an incident of profiling, it must be noted that both the cops and kids in the story are Latino, and profiling is both complicated and not practiced only by whites. There was a very long back-and-forth exchange about this and about profiling in certain communities last night on my Facebook page. If you're interested in more of that debate and the story about the kids please check that out here.