New ‘Build Better LA’ Ballot Initiative Would Require Affordable Housing and Local Hiring

2:06 PM PST on February 19, 2016

A coalition spearheaded by the L.A. County Federation of Labor, announced Thursday that it has filed language for a ballot initiative that supporters say will increase affordable housing and jobs in the city of Los Angeles.

If approved by voters, the initiative would require developers seeking zoning changes and general plan amendments for projects to build, or pay a fee toward the construction of, affordable housing. The “Build Better LA” initiative, in addition to requiring affordable housing construction, also has a local hiring provision.

“L.A. is growing; growth is desirable,” said Sandra McNeill, executive director of T.R.U.S.T. South L.A., a community land trust. T.R.U.S.T. is part of ACT-LA (Alliance for Community Transit - Los Angeles), which has partnered with the L.A. County Federation of Labor and the Los Angeles/Orange County Building and Construction Trades Council to form the Build Better LA Coalition.

But, she said it is important to take proactive steps to make sure that that growth is inclusive.

Here is a copy of the language submitted by the Coalition [PDF], which cites the lack of housing, especially that which is affordable, and the city’s inability to meet the growing need for affordable housing on its own, as the impetus for the initiative.

Briefly, the Build Better LA initiative would require to developers who sought a zoning change or general plan amendment to choose between setting aside five percent of the units to be rented to extremely low income tenants and six percent rented to tenants at who qualify as very low income. Or, developers could opt to set aside five percent of the units for extremely low income tenants and 15 percent for low income tenants. The definitions for these income levels are a percentage of the county-wide area median income (AMI) and are adjusted for household size. In 2015, the California Department of Housing and Community Development reported that L.A. County’s AMI was $64,800 for a four-person household.

It would also create an affordable housing incentive overlay district within a half-mile of major transit stops.

Those districts, referred to as “Transit Oriented Community” (TOC) districts, would offer incentives for developers willing to build housing that has, at minimum, set aside 11 percent of the units for very low income tenants or 20 percent for low income tenants. There is a provision for city officials to establish an extremely low income category as well for these districts.

There are a variety of ways developers can satisfy these requirements, including paying in lieu fees to the city’s housing trust fund.

There is a local hire provision as well which requires contractors to make a “good faith effort” to assure that at least 30 percent of the workers on a project are permanent residents of Los Angeles and another 10 percent are transitional workers who live nearby.

Affordable housing advocates have long criticized the fact that Los Angeles does not have a city-wide inclusionary housing policy and efforts to create one have been stifled, most recently by a 2009 California appellate court decision, which ruled that the city’s attempts to require developer Geoff Palmer to include affordable housing in a private development violated the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act.

Neighboring cities like Santa Monica and Pasadena, however, do have inclusionary requirements on the books. In Santa Monica, at least 30 percent of all new housing built has to be affordable to households making 80 percent of AMI or less.

McNeill points out that the Build Better LA initiative stands on its own in taking a proactive approach to more equitable growth in the city. But the no-growth group Coalition to Preserve L.A., which filed its own initiative several months ago that would put a defacto moratorium on growth in the city by ending the practice of allowing for zoning changes and general plan amendments for individual projects, seems to see the Build Better LA initiative as a counterattack and has gone on the defensive.

Jill Stewart, the former L.A. Weekly editor-turned-spokesperson for the no-growth group Coalition to Preserve L.A., is attacking the labor-backed initiative. In the L.A. Times, Stewart called it “a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” repeating the no-growth trope that affordable housing incentives would lead to “diminished quality of life.”

The Coalition to Preserve L.A.-backed initiative, spearheaded by AIDS Healthcare Foundation President Michael Weinstein, would not only end the practice of zoning changes and general plan amendments, the mechanisms by which the Build Better LA initiative hopes to get developers to build affordable housing, but it would also prevent updates to any of the city’s 37 community plans from allowing increases in height or density, essentially freezing the city’s built environment in place as it is today.

The initiatives are not in direct competition, but if Build Better LA initiative receives more votes than the no-growth initiative, it would prevail in instances where the two initiatives are in direct and irreconcilable conflict.

It is not clear exactly how the Build Better LA initiative would impact future housing growth, since it would likely increase construction costs. Still, unlike the Coalition to Preserve L.A.’s initiative, the Build Better LA initiative allows for future growth in a city currently experiencing a staggering housing shortage.

Both initiatives speak to frustrations that many people have with the city’s planning process.

Part of the problem is that much of Los Angeles zoning has not seen any real significant updates since the post-war suburban housing boom. While the city is comprehensively retooling the outdated code to bring it up to date, over the decades an ad-hoc system of convoluted and less-than-transparent workarounds has developed.

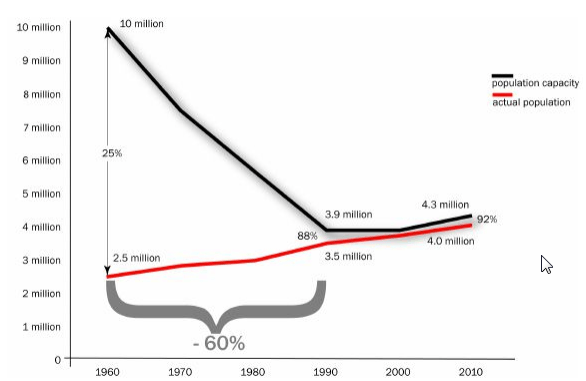

In the 1980s and 1990s, the city of L.A. saw its zoned housing capacity cut by more than half as a result of anti-growth political movements. The consequences of decades of downzoning, failure to upzone where needed, and general resistance to growth, especially on the westside where many good jobs are located, are beginning to become more pronounced. Displacement is growing, economic segregation is deepening, and traffic is getting worse, since the people who work in those communities have no choice but to commute greater distances.

Now, as the demand for new housing is not being met, displacement is growing as a problem. Desirable areas have become essentially gated communities by resisting housing growth, forcing newcomers to search for homes in less-affluent areas where they compete with lower-income residents for scarce housing.

In short, the region has decades of housing growth shortfalls to make up for before it will begin to see housing costs leveling off. The California Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates the region has an overall housing deficit of about one million units.

If it passes, the Build Better LA initiative would help L.A.'s affordability situation, but it would likely not go far enough to solve the crisis. Build Better LA can not address all of the L.A.'s affordability problems, including organized resistance to much-needed mixed-income housing growth, especially on the westside.

In Santa Monica, resistance to housing growth has not been abated by the inclusionary zoning laws. Overall, growth there is relatively slow and expensive. One need only look to the demise of the Bergamot Transit Village project to see how even inclusion of affordable housing does not make a project immune to anti-growth politics. The Bergamot Transit Village was proposed at a former Papermate factory site across from the future Expo Line 26th Street Station. A seven-year process, during which the Santa Monica City Council negotiated for about 100 of the nearly 500 new housing units to be reserved for lower-income residents, especially seniors, was scuttled in the 11th hour because activists, motivated by fears of increased vehicle traffic, successfully gathered enough signatures to qualify the council’s approval of the project for a referendum.

Inclusionary housing requirements would provide a mechanism to keep some housing affordable in parts of Los Angeles that have been made newly-desirable by the Metro’s expanding rail network.

Affordable housing, the kind which the Build Better LA initiative would mandate, is very important for improving many Angelenos lives. Unfortunately, it is really only a small part of the solution to the region’s housing crisis. According to a May 2014 report by the Southern California Association of Nonprofit Housing cited by the initiative, the region had a shortfall of about 500,000 affordable units.

When affordable housing becomes available, nonprofit housing providers are swamped by the number of people vying to get in.

Sahra Sulaiman, reporting on Metro’s affordable housing guidelines, illustrates the problem:

Approximately 8000 families applied for the 184 units of affordable housing that the East L.A. Community Corporation has built in Boyle Heights and East Los Angeles recently. 1500 families vied for a spot in the 60-unit residence on Whittier Bl. built by the Retirement Housing Foundation last March. And RHF was expecting as many as 2500 applications for the affordable, 78-unit senior residence set to open next door. More than 1000 families applied to live in a 90-unit residence in Macarthur Park built by McCormack Baron Salazar on land owned by Metro. And these figures likely don’t include the folks who are desperate for housing but do not earn the minimum amount required to qualify for consideration.

Then there is the question of the growing group of people who may make too much money to qualify for affordable housing and not enough money to comfortably afford market-rate housing.

As noted in a recent report from the LAO, the only way to realistically get rents within their reach is to allow for more housing growth, which, in turn, helps keep the rents in older buildings lower. This has been shown to actually mitigate displacement of lower-income, long-term residents, as well. That's especially important for tenants living with extended families that may be too big to be accommodated by available affordable housing options.

In short, Los Angeles -- and its neighbors -- need to build a lot more housing at all levels of affordability and in the right places, namely near jobs and transit. The no-growth "Neighborhood Integrity Initiative" would stifle this needed housing growth. The Build Better L.A. initiative could at least make an dent in the massive demand, but further work will still need to be done to foster solutions to the region's deepening affordability crisis.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Los Angeles

Automated Enforcement Coming Soon to a Bus Lane Near You

Metro is already installing on-bus cameras. Soon comes testing, outreach, then warning tickets. Wilshire/5th/6th and La Brea will be the first bus routes in the bus lane enforcement program.

Metro Looks to Approve Torrance C Line Extension Alignment

Selecting the relatively low-cost hybrid alternative should help the oft-delayed South Bay C Line extension move a step closer to reality