Yesterday afternoon, while waiting for a late 720 bus, Boyle Heights Beat Editor Antonio Mejías-Rentas tweeted out the story of a vendor he observed being moved off the corner at Whittier and Soto.

The complaint call had come in to the LAPD Hollenbeck station around 11:45 that morning, according to Captain Al Labrada. A business owner in the area alleged that the vendor was attempting to sell flowers in the roadway.

It's not typically how vendors operate. Nor is it something Mejías-Rentas observed while he was there.

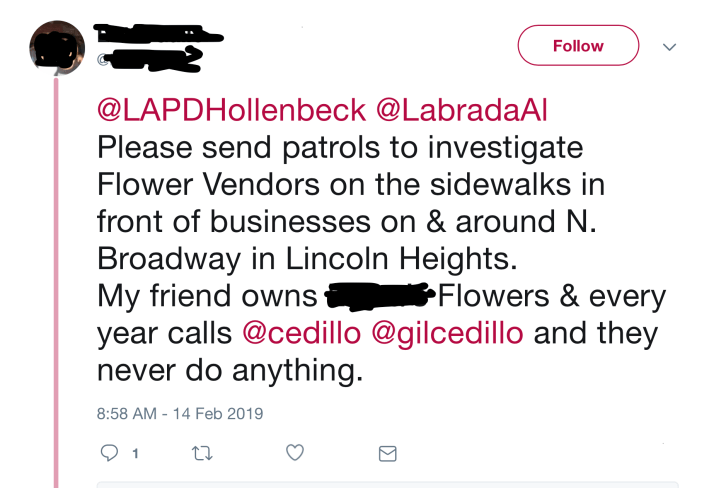

What is more typical is that brick-and-mortar businesses call the cops on vendors. Especially if they are specialty stores who do their biggest sales around holidays. Like yesterday.

The problem is, brick-and-mortar shops can't do that anymore. Neither can people who simply don't like them.

S.B. 946 - the Safe Sidewalk Vending Act - went into effect earlier this year, legalizing sidewalk vending and limiting excessive local control over the streets and public spaces vendors can access.

The bill prohibits caps on the number of vendors within a city, prohibits the limiting of vendors to designated areas within communities, prohibits requirements that vendors first obtain permission from businesses or individuals to access a site, and requires that any restrictions placed upon vendors be explicitly tied to “objective health, safety, or welfare concerns.”

The need for any concerns to be "objectively" tied to health safety or welfare is so a business can't call the cops on a vendor because they view them as competition. There must be evidence of real or potential harm.

Which may be exactly what happened yesterday. Labrada noted there is a florist on the opposite corner.

But instead of educating the business owner on the new law and enforcing it, the officers approached the vendor, relayed the complaint to him, mentioned that the vendor was also said to be blocking the sidewalk (something that was also not the case), and asked that he move.

“Me dijeron que alguien se quejó”, the vendor told me, said vendors in three other corners were shut down as well. “Que vuelven en una hora”, he added; the officers told him they’d check back with him in an hour. pic.twitter.com/fYg1wepSCu

— Antonio Mejías-Rentas (@lataino) February 13, 2019

For the vendor, Mejías-Rentas reported, this posed a significant hardship.

The man slowly packed up his goods around 1:30 p.m., hoping to make a last sale or two as he did. Even if he were to move to another corner, just the time lost packing up, finding a new corner where he was easily accessible and not impinging on another vendor, and unpacking his wares meant lost revenue. Plus, few spots offer the kinds of foot and car traffic the intersection of Whittier and Soto does.

On an already crappy day, it was disheartening to say the least.

“I’m picking up my stuff as slowly as possible,” he said hoping he’d get in another sale. Talk about getting your ❤️ broken right before Valentine’s. He’d only been set up a short time he said as he s l o w l y wrapped a papaya. pic.twitter.com/AitWP0snsm

— Antonio Mejías-Rentas (@lataino) February 13, 2019

Labrada is no stranger to the issues around street vending. He has met with members of the L.A. Street Vendor Campaign on a number of occasions and has kept close watch on the legislation. And with the spate of armed robberies perpetrated against vendors recently and their general vulnerability, he said, he is eager to work with vendors and ensure their safety.

He has discouraged his officers from citing vendors for some time now, he said, underscoring the need for compassion. And he says he has asked that, should there be a call regarding a public health violation, he be notified so he can assess the situation and determine the appropriate response.

When pressed about why the vendor was asked to move given that his right to be there was now protected, Labrada said simply that they had had to react to a call for service.

If they didn't let this vendor know of the complaint and act accordingly, he continued, then it was likely the station would continue to receive complaints about the vendor until some action was taken.

When pressed again about the fact that the vendor had the right to be there, Labrada pointed to the slow pace at which the city council has moved on finalizing and implementing the vending ordinance.

Although an ordinance was hastily pushed through council just before the end of 2018 after years of delay, the permit system has yet to be formalized. Vendors will eventually have to apply for permits, pay set fees, and, if selling food, take training courses and follow all health regulations to retain and renew their permits.

The fact that officers can't currently point to a physical permit as a way to push back against a business owner's unlawful demands seems to make the ordinance appear to exist in more of a gray area than it actually does.

There's "no set standard" with regard to how they are supposed to balance the interests of vendors with those of the businesses, insisted Labrada.

Making the easier thing to do, it appears, to err on the side of accepting the complaint came in in good faith and asking the vendor to continue selling from a different location.

To get more clarity on this issue, Labrada said he had already reached out to the city attorney's office and would be sure to communicate any necessary adjustments to enforcement practices with his officers. But, he said, he really was eager to see the formal permit process finally take shape.

He had no desire to see vendors pushed out of the community and would be willing to speak with the vendor if need be, he said. "I am always about finding a space for everyone."

For that vendor on one of the busier days of the year, however, that space unfortunately was not at Whittier and Soto.

Many thanks to Antonio Mejías-Rentas for alerting us to this story and his help in reporting it. Follow him on twitter, here.