The recent wildfires have helped spotlight questions of air quality of late.

But while on a retreat with staff and members of Communities for a Better Environment (CBECal) up near Mono Lake, which was experiencing fires at the time, says Community Organizer Xugo Lujan, they checked their air quality monitors to find that they were breathing in levels of particulate matter similar to those found on a normal day in Southeast L.A.

Although not particularly surprising, the finding was still striking, says Lujan, and one that got retreat participants talking about how to address air quality issues in their own neighborhoods.

It also got Lujan thinking about how to make Angelenos aware of the ongoing emergency in EJ communities* on the Eastside and in Southeast L.A. (*disadvantaged communities that suffer disproportionate risks to their health and quality of life due, in part, to environmental factors).

Certainly, there had been an outcry when the extent to which the lead-acid battery recycler Exide had showered those communities with lead emissions finally became apparent. But once Exide was shuttered, the communities found themselves largely having to fend for themselves again.

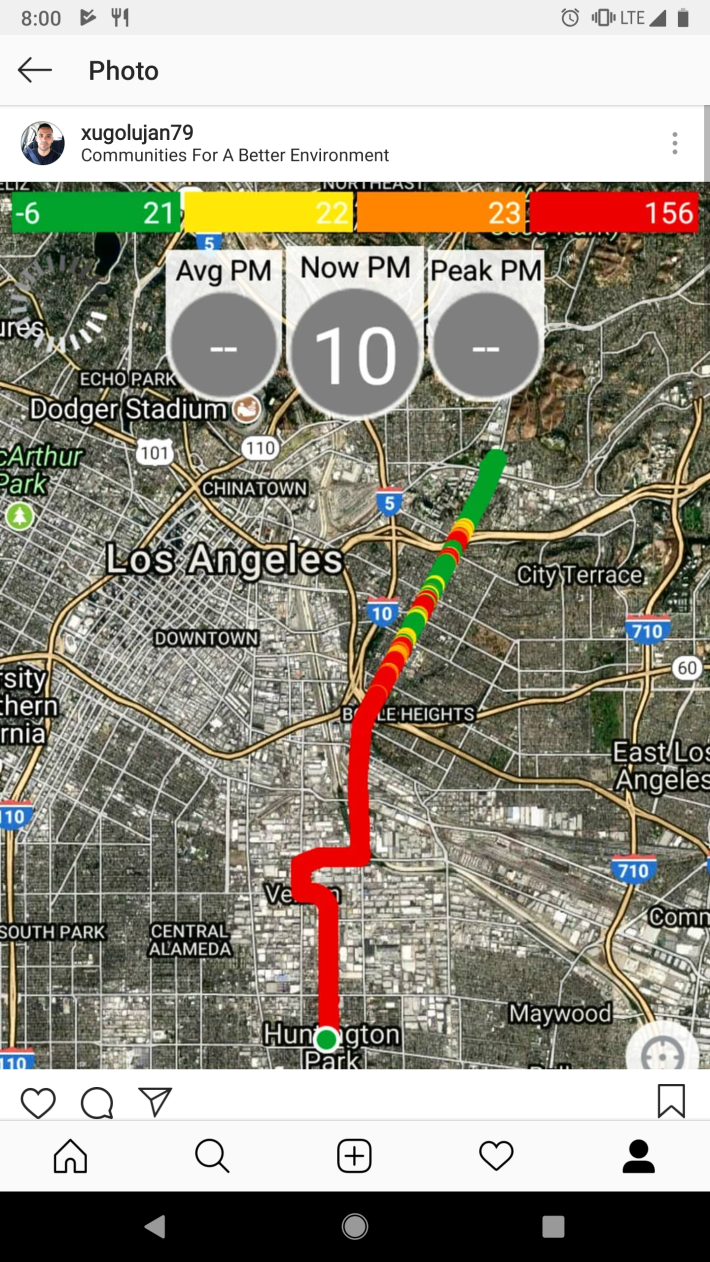

So, Lujan attached a portable monitor that measured particulate matter to his bicycle before commuting from Boyle Heights to Huntington Park one day to see what it might capture.

Moving through Vernon and other industrial areas on his way home at night, he says, he can see the larger particles clogging the air in his headlamp. It makes him all the more fearful of what he can't see.

Particulate matter (PM) particles form in the atmosphere as a result of chemical reactions between pollutants, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Most dangerous among them are particles smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter, or PM2.5. Composed of a mix of carbon, sulfate, and nitrate compounds and soil and ash and tiny enough to fit thirty within the width of a human hair, they are able to pass easily through the lungs into the bloodstream. They are linked to a number of ailments, including asthma, cancer, and heart disease.

Forest fires are a significant source of PM2.5. But so are construction activities, smokestacks, and diesel cars and trucks - things the industrial areas of Boyle Heights and the Southeast Cities have in abundance.

But getting neighborhood-level data is no small feat. The methodology detailed by USC's Crosstown Initiative suggests it involves calculating how raw data compiled from 12 EPA sensors interacts with the physical geography and topography of the city. Similarly, typing your zip code into the AirNow mapping tool gives you a look at the air quality over a 24-hour period, but not necessarily the extent to which air quality changes in real time or the impact specific emissions sources can have on a neighborhood.

Lujan has already recruited around 30 residents who have agreed to have monitors installed on their homes to help serve as a constant source of crowdsourced data. While there is still room for improvement in the quality of the data these smaller sensors are able to capture, environmental justice groups that upload their data to the Coalition for Clean Air's PurpleAir Map are at least able to provide a snapshot of variations seen within and across communities.

Lujan is now seeking cyclists who ride in and around Boyle Heights and Southeast L.A. to aid him in capturing measurements of particulate matter by agreeing to attach monitors to their bikes. He wouldn't need them to ride with the sensors every day, he says. Rather, he hopes to organize, train, and lead them on regular rides through specific zones bordering residential areas where toxic emissions are believed to be a problem. Working directly with area residents on this project, he hopes, would have the added effect of engaging them on the threats to their own health and that of their neighbors.

The home monitors should be installed this month, says Lujan. He would like to have amassed enough volunteer cyclists to host a training workshop in mid-January and run test rides soon after.

Do you ride on the Eastside or in the Southeast? Would you like to participate in this project? Please reach out to Lujan at Xugo[at]cbecal.org or (323) 826-9771.