"Yeah, I knew him..." said the man on his bike outside the liquor store at 33rd and Central Avenue. "He was my neighbor."

We were chatting about the new light poles going in at the intersection while gazing at the memorial for Jorge Alvarez on the opposite corner. The 51-year-old cyclist had been killed in a horrifying hit-and-run the week before Christmas, tossed fifteen feet into the air by a driver that never slowed down and never looked back.

It's a shame fixes don't seem to go in until after too many people have died, we lamented.

Central Avenue has long been known as one of the more pedestrian- and bike-unfriendly streets in the city. It is a fast-moving thoroughfare (especially at night) whose traffic patterns are made more complicated by the number of heavy trucks that trundle down it around the time that school lets out.

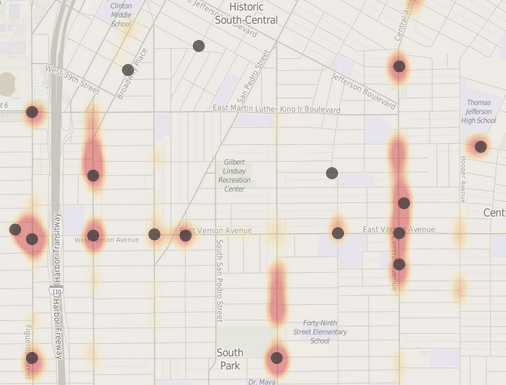

The L.A. Times' mapping project vividly illustrated just how unkind the street has been to its most vulnerable users (below).

Twelve of the avenue's intersections made it onto the list of the county's 817 most dangerous - four of which are located within just blocks of each other. And while 33rd hadn't seen a fatal collision between 2003 and 2013, it had seen 14 pedestrian crashes and two bike crashes (and likely many more that went unreported), in addition to eight other car crashes.

Safety improvements are long overdue, but they have been hampered by the fact that councilmember Curren Price had Central Avenue removed from Mobility Plan 2035. The move effectively nixed the seven-plus mile bike lane that would have connected commuters moving between Watts and Little Tokyo.

Even after the avenue was designated a Great Street, Price worked with the Mayor's Office to ensure that the community had as little say as possible in the discussions around the redesign of the corridor. This, despite the fact that Central Avenue is one of the city's most heavily bike-trafficked streets and the fact that the overwhelming majority of those cyclists are residents and/or work in the area and are riding out of necessity. Months of campaigning by community members and TRUST South L.A. aimed at getting Price to understand his constituents' plight were ultimately for naught.

The lower-income African-American gentleman I was speaking with had not been a part of any sort of organized effort to see the bike lanes implemented, he said. But he had signed a petition in favor of the lanes. His bike was his transportation for work and everything else, he said, and he and his neighbors just wanted to feel safe moving around their community. Knowing his neighbor had been so easily and brutally run down was unsettling.

The motion to implement the new signal at 33rd was introduced in early December and approved on December 15 - sadly, just days before Alvarez was killed.

According to the council file, $40,000 in redevelopment funds will be used to implement a full new signal, not just a lighted crosswalk. Hopefully, this will help to slow the street down both at this intersection and the dangerous blocks leading up to it from either direction.

Because it's not just pedestrians and cyclists who are at risk.

Thanks to the history of redlining and haphazard zoning in the area, overcrowded residences are tucked in alongside schools and commercial structures up and down the corridor. Meaning that however busy it gets, Central is still fundamentally a neighborhood street in a densely populated community. Traffic violence can have real consequences in such a context, as we saw this past December, when a drunk driver careened into a building a few blocks north of 33rd, killing a five-year-old boy sleeping in his family's apartment.

One lone signal on a fast and busy street is not enough to ensure such things can't happen again. But for now, it means that Jorge Alvarez' neighbors will be a little safer. And for that, the many people I watched wait way too long for drivers to let them use the crosswalk this past Sunday will be grateful.