Republished from Better Institutions with permission of the author.

On March 7th, Los Angeles is going to vote on the type of city it wants to be.

The vote will be over Measure S, formerly known as the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative (NII), which seeks to limit housing development in the city. Backers of the initiative claim that City Council is too beholden to developers, and that the pace of new housing and commercial development in the city is out of control. They also express concern that "mega projects" are making Los Angeles less affordable, since few new homes are being targeted at low and moderate income households.

Opponents, like myself, argue that passage of Measure S will be a catastrophe for the future of the city: New housing is the only thing keeping rents from growing even faster, and anti-development advocates are making a grievous error when they view new luxury housing as a cause of rising prices, rather than a symptom of them. It will throw the baby out with the bathwater, leaving us with fewer low-income units and more expensive housing for every other resident of L.A. Opponents also view the NII as a fundamentally pessimistic initiative—one which essentially asserts that Los Angeles' best days are long-since past.

It's a really bad plan, but calling Measure S "bad" doesn't go nearly far enough. It is, in fact, the Donald Trump of ballot initiatives. It’s a cynical effort to co-opt a legitimate sense of frustration—frustration felt by those who haven’t shared in the gains of an increasingly bifurcated society—and to use that rage and desperation for purely selfish purposes. It invites us to vent our frustrations and, in so doing, to further enrich those who helped to engineer our ill fortune. And as with Trump, a Measure S victory will roll back the clock on years of steady progress.

Since I think there are a lot of folks out there who genuinely haven't made up their minds about the initiative, or aren’t yet familiar with it, I'd like to summarize some of the most important reasons to oppose it when it comes time to vote this March.

1 - It will mean fewer affordable housing units for low income households.

The Coalition to Preserve L.A., which is backing the initiative, is turning this into a referendum on housing development in Los Angeles. They're arguing that new homes have “wiped out thousands of net units of affordable housing and directly fed into L.A.’s spike in homelessness.”

It’s true that we’re losing affordable housing units in L.A., but it’s not because they’re being torn down to build new luxury housing, by and large. Most affordable housing units have 30- to 55-year covenants which, upon expiration, cause the homes to revert back to market-rate. At that point, the owners are free to charge whatever tenants are willing to pay for the unit. From 2015 to 2020, about 15,000 such covenants will expire without additional public funding. By comparison, just 1,900 multifamily units were torn down between 2010 and 2014, and over 5,600 low- and very low-income affordable units were permitted. Many of those affordable homes were constructed at no cost to the public, as part of market-rate developments taking advantage of the state’s density bonus program.

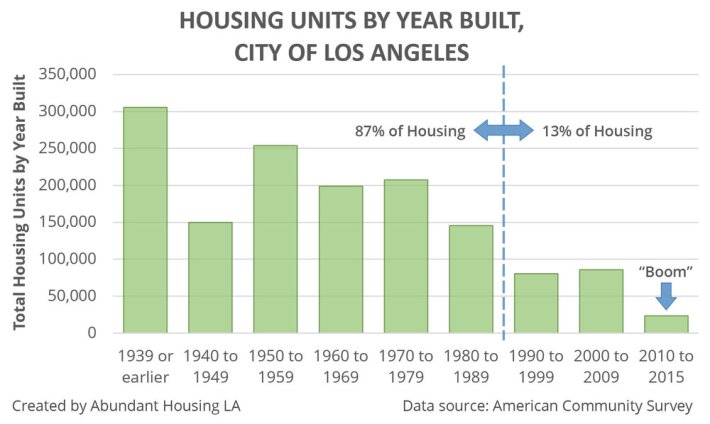

Measure S's additional restrictions on development mean that less new housing will be built while affordability covenants continue to expire. This isn’t an issue of affordable housing being torn down to build expensive skyscrapers, it’s a case of resting on our laurels. We’ve built less housing in the past three decades than at any time since before the 1940s—including housing with affordability covenants—and now the chickens are coming home to roost. The initiative seeks to solve our problems by paradoxically doubling down on this failed strategy.

Part of the problem with our inability to build affordable housing is that we’re suffering from a severe shortfall in funding, with dedicated affordable housing funding sources falling by nearly 80 percent since 2008. But again, this has nothing to do with housing development more generally, and the NII’s backers have no answer for how their initiative will create or preserve subsidized affordable housing.

On the contrary, the initiative actually includes a variety of new rules that will make it even more challenging to develop affordable housing. For example, it will force developers of permanently supportive housing to build excessive parking for formerly homeless individuals, adding approximately $30,000 to $50,000 per unit to the cost of development—despite evidence from past projects that the vast majority of residents will never own a car. Requiring millions of dollars’ worth of parking that we know will never be used is not how we’ll improve affordability in Los Angeles, nor are any of the other new laws and regulations that would be added by the NII.

2. It will also make the city less affordable for everyone else.

Measure S will make it tougher to build the few hundred (or thousand) affordable homes we permit each year, but it will be an absolute disaster for the more than one million market-rate homes in the city.

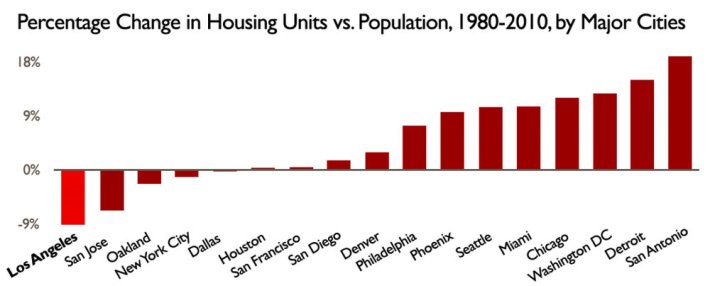

A variety of reports have linked the high cost of housing to an undersupply of housing, with a particular emphasis on the failure of coastal cities like Los Angeles. As a general rule, when a city grows its population and employment faster than its housing supply, prices increase more rapidly. This chart from the city’s recently-adopted Comprehensive Homeless Strategy highlights how poor a job L.A. has done relative to peer cities:

The vacancy rate for rental housing in Los Angeles is now under 3 percent, fourth-lowest in the nation and a major contributor to rapidly rising rents. Higher vacancy rates mean landlords must compete for potential tenants; under about 5 percent, landlords hold the leverage as potential renters are forced to compete for a very limited supply of housing. We’ve been under 5 percent vacancy since 2011, and Measure S will guarantee that we stay there for the foreseeable future. That's good news for property owners, and bad news for the two-thirds of L.A. residents who rent their homes, and for anyone who cares about equity or affordability.

The pro-initiative folks will tell you that this is all irrelevant, since the new housing is all targeted at rich people anyway. Putting aside the fact that those luxury units are often accompanied by on-site affordable housing, they’re still wrong. Going back all the way to the bungalow era, new housing has almost always been targeted at higher-income residents. Over time these new units age, better options become available, and the older ones “filter” down to moderate and lower income households. We understand this intuitively when it comes to cars—we would be surprised if we learned that a friend of modest means had purchased a 2016 Honda Civic, but not a 2008 model—but fail to apply the same logic to housing. In one paper, author Stuart Rosenthal found that residents living in 20-year-old housing earned about half as much as residents in new units. Unfortunately, Los Angeles has very little 20- and 30-year old housing thanks to decades of anti-development sentiment. The NII would guarantee that we're in the same position 20 more years in the future.

Other recent research has shown that Bay Area communities that built a lot of housing experienced about half as much displacement as communities that built very little. San Francisco is one of the few cities in the U.S. that has taken a stronger anti-development posture and has spent more on affordable housing (per capita) than Los Angeles. Despite this principled stand, San Francisco is now dramatically more unaffordable than L.A., and it is doomed. How will adopting more SF-like policies lead to a more affordable city? The initiative’s backers have no legitimate response, and that should scare you.

They would love for you to believe that by supporting Measure S you will stop evictions and house-flipping—that you will "Save Our Neighborhoods." The bare fact, though, is that stopping new development will only make matters worse. New residents are moving here whether or not we build homes for them, as they have for decades; the question is whether investors are allowed to use their capital to build new units to house them, or they're forced by the NII's restrictions to spend their money elsewhere, upgrading existing homes, ultimately increasing evictions like those seen at the Westwood Senior Center and further supplementing the wealth of those lucky enough to own property in Los Angeles. Measure S does absolutely nothing to prevent this kind of investment, and by blocking new development it will only accelerate the impacts on our existing housing stock.

3. It's disingenuous.

As you've already read, there's a lot about this initiative that's rooted in false promises.

Perhaps the most disingenuous aspect of this proposal, though, is the apparent motivation behind it. Michael Weinstein, head of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, has been the driving force behind Measure S, and was driven to action by a two-tower project adjacent to his Hollywood offices. He and his team have said that the project is out of scale with the neighborhood, but that claim rings hollow when the office of Weinstein himself is next door, on the 22nd floor of the Sunset Media Tower.

Given that this is just a few feet shorter than the proposed Palladium residences, one is inclined to ask: If a Hollywood tower was good enough for you and your organization to call home, what’s so horrible about a few more springing up nearby, giving people new places to live and work just a few blocks from a Red Line subway station? Wouldn’t that help create a more cohesive community character? Maybe, just maybe, it has more to do with the loss of a beautiful view and a cheap parking spot than anything as principled as “the future of the city.” Just a thought.

Not only that, but the campaign moved Measure S from its initial place on the November 2016 ballot to the 2017 ballot. Why? They'll tell you that it was because they didn't want to be drowned out by the many other initiatives in a crowded election. The truth, though, is that they know this is an initiative that is targeted at older homeowners who have nothing to lose from a less affordable, less inclusive Los Angeles. It was naked ballot shopping, and its goal amounts to a subversion of democracy: rather than go to a vote when 70% of registered voters are participating, they delayed until the municipal election when turnout hovers around 15%, and when older voters dominate. It's a cowardly act, and an admission of their initiative's broad unpopularity. And if we don't turn out in March, it'll work.

4. It will destroy thousands of well-paying construction jobs.

Measure S would put a two-year moratorium on all development that requires a General Plan amendment, zone change, or height district change, including projects that have already been approved but haven’t yet been issued a building permit.

There are approximately 223,000 people employed in the construction industry in the L.A. metro area; assuming employment is roughly proportional to population, about half are probably employed or perform a substantial amount of work within the city of L.A. Many of those individuals would lose their jobs, and be forced to either take poorer-paying jobs outside their field, or leave the city altogether, since two years is far too long to wait for the dust to settle and see if those jobs return. A recent study by Beacon Economics confirms this, estimating the loss of 12,000 jobs in just the first year of Measure S's passage.

If housing affordability is a sincere aspiration of this initiative (it’s not), it’s hard to see how putting tens of thousands of residents out of work will help achieve it. Amazingly, the campaign director brushed off this concern by arguing that L.A. "will be awash in jobs" thanks to the recent passage of Measure M—an initiative that the Measure S team opposed, by the way. These are not people who are actually concerned with the well-being of Los Angeles residents.

5. It will mean more traffic, not less.

Another argument made in favor of Measure S is that traffic is out of control, and that we need to limit new development to get a handle on it. Further, the initiative includes parking requirements that ensure every project builds plenty of parking, so no one has to hunt for a good spot.

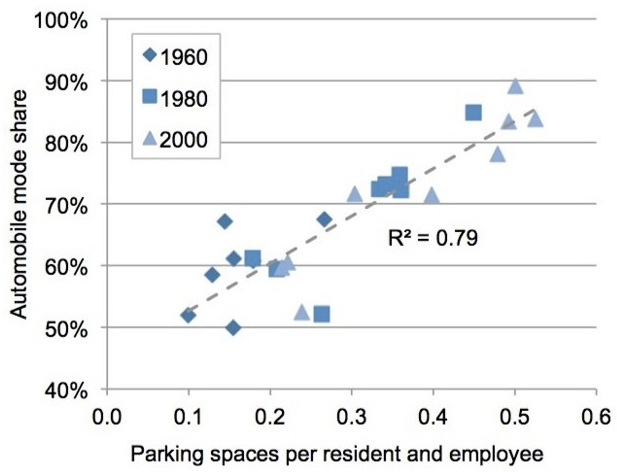

Though intuitive, this is backwards thinking, yet again. For one, the parking requirements in the initiative will be counterproductive, leaving residents with less on-street parking and worse congestion. This is because as the supply of parking increases, it actually encourages more people to drive. And it’s not a simple case of correlation rather than causation: More parking built in one 20-year period led to significantly more driving in the next; when the authors used the same method to see whether increased driving led to more parking, the relationship was far weaker. By forcing developers to oversupply parking spaces, neighborhoods will be inviting more people to drive there rather than bus, walk, or bike.

Traffic will also worsen as a result of the aforementioned affordability impacts. As rents continue to grow—due to the initiative’s guarantee that vacancy rates stay under 5 percent—fewer and fewer low and moderate income households will be able to call Los Angeles home. Most of the “affordable” housing in L.A. is actually just cheap market-rate housing, and current residents will be able to stay so long as they’re protected by rent control. But when they move out, their unit will go to a higher-earner. Higher-income households drive much more than low-income households, so future L.A. residents can expect considerably worse traffic in their affluent utopia.

If we want to fix our transportation system, it's going to require new infrastructure and redesigning our neighborhoods. Freezing our communities in amber will only ensure that more and more Angelenos of modest means are forced to leave. We will push out many of our neighbors who walk, bike, and take transit to work, replace them with those who primarily drive, and in the end we'll still be stuck with the same broken transportation network that we've got today. The only way out is through, not back. Let's not fall for the false Trumpian vision of Making Los Angeles Great Again.

6. It commits us to permanently under-funding our shared infrastructure.

As a justification for its many code amendments, Measure S argues the following:

The development of projects containing a significant component of multifamily housing has an adverse impact on health and safety when such projects are approved in areas that are not currently zoned for housing on such a scale or which do not currently permit housing on such a scale under the General Plan, because the City's infrastructure is threatened, in that fire response times do not consistently meet standards for safety, the City's water supply is reliant on an aging infrastructure that must be upgraded and streets that are in failing condition.

This harkens back to 1926, when in their Euclid decision the U.S. Supreme Court described apartments as "mere parasite[s], constructed in order to take advantage" of attractive residential districts. We’re expected to believe that the quality of our city’s infrastructure will be further degraded by the addition of new households—especially multifamily homes—but nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, our infrastructure is in such bad shape because we have so much of it, per capita, which is a result of our sprawling single family character. There are too many roads, pipes, and cables for us to maintain because we’re so spread out; the best way to fix that problem is to reduce the amount of infrastructure that every person is responsible for. We can’t really tear out most of our roads and sewers, so that leaves adding more people as the obvious solution.

Smart Growth America has reported that increased density saves cities an average of 10 percent on service delivery, and this shouldn’t surprise anyone. If you build a new apartment building in Hollywood you don’t need a new fire station or police precinct—there’s already one that services the area. You don’t need new mainline water or sewer pipes because they’re already in the road and have plenty of extra capacity. The developer pays for connections to all of these citywide infrastructure systems, and the residents’ tax dollars help contribute toward much-needed upgrades. Half-full buses and trains become 75-percent full at no additional cost to Metro, increasing their revenue and funding additional service. Fifty people live along the sidewalk rather than 30, so each person's share of maintenance drops just a bit.

The Coalition to Preserve L.A. wants to pit existing residents against future ones, but we have every reason to be friends. Our city has the jobs, amenities, climate, and quality of life that they desire; they have the tax dollars that will help us preserve and upgrade our city’s infrastructure. And hey, people can be pretty great. All my best friends are people. We should welcome them with open arms.

7. It's a fundamentally pessimistic vision for L.A.'s future.

To me, this last point is the most important reason to oppose Measure S.

As Civic Enterprise co-founder Mott Smith said in an interview last year, this initiative is “a choice between thinking that L.A.’s best years are behind us, or thinking that L.A.’s best years are in front of us.” The Neighborhood Integrity Initiative sees no promise in the Los Angeles of the future.

It’s a belief, made law, that L.A. can never become better than it is today. That it can never again reinvent itself for the better, as it has numerous times in the past. That our city has reached its pinnacle, and now the best we can hope for is to balance precariously upon this perch, neither adapting to the future nor rediscovering our past.

It is ironic that in our most liberal cities—where the affordability crisis is at its most severe—we are at once passionately supportive of immigration to our country, while staunchly opposed to the migration of new residents to our cities. We belittle conservatives for turning their backs on poor, ambitious immigrants, and yet we deny millions of potential neighbors the freedom to join us in the world’s most productive and exciting communities. We welcome diversity and celebrate inclusion, but only if you already live here. But just as welcoming new residents to our country has always led to a stronger, more resilient population (albeit with growing pains along the way), so too is growth an essential, positive, and equitable trajectory for our cities.

This March, I hope we’re able to re-capture that spirit of inclusion, and that we can come together in favor of a more hopeful vision for the future of Los Angeles. I think we've had enough of fear and false promises, don't you?

Measure S will appear on the March 7 ballot; you should receive election information from the city sometime in February. This initiative is only for City of Los Angeles voters. The last day to register for the March 7 election is February 20, fifteen days before the vote. If you need to register or are unsure of your voter registration status, you can quickly check on it here.

Turnout in municipal elections is extremely poor (10 to 15 percent of registered voters actually cast a ballot), so your vote really matters in this election. Please show up and vote No on Measure S!

Shane Phillips is the Project Director of Los Angeles Streetcar, Inc. and volunteer Policy Director for Abundant Housing L.A. He blogs at Better Institutions and blogs at Better Institutions.