Every year Census data comes out revealing which cities are growing fastest. But what the numbers don't tell us is what kind of growth is occurring and where.

Yonah Freemark at the Transport Politic set out to get a better understanding of growth patterns in major cities. Looking at long-term changes since 1960, the big upshot is that even in growing cities, the close-in, urban areas don't account for the changes -- instead annexation and sprawl drove the population gains. He writes:

When examining just a comparison between changes in population in the city as a whole and those in the neighborhoods that were already built up in 1960, some remarkable trends become apparent.

As the following interactive graph shows (mouse over the graph to get more information; not all cities are shown in the X-axis), very few cities saw significant overall growth between 1960 and 2014 in neighborhoods that were already built up. Houston and San Antonio, which each gained hundreds of thousands of people overall during that period, also each lost more than 100,000 people in their already-built up areas. So did Indianapolis, Columbus, Louisville, and Memphis. What’s surprising is that these are cities often acclaimed for their dramatic growth over the past few decades. Yet their growth has been premised largely on annexation -- suburbanization -- even as their already-built up cores have declined.

In fact, the average of the 100 largest cities grew by 48 percent overall. Yet the average city also lost 28 percent of its residents within its neighborhoods that were built up in 1960.

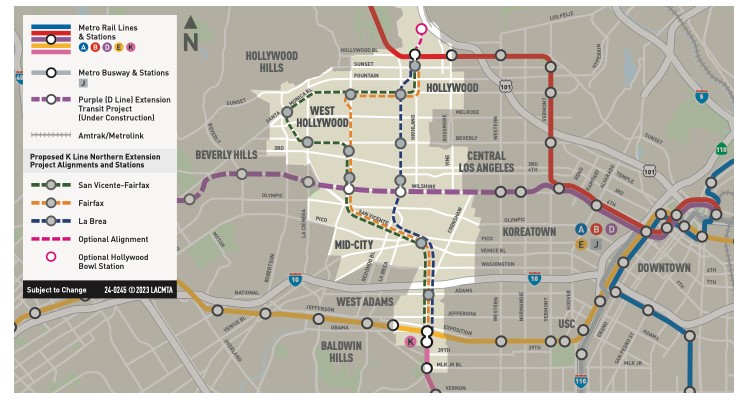

Some cities did expand through infill quite dramatically, and Los Angeles is a true outlier on this front, gaining almost 1,000,000 people in areas that were already at least partially built up. Other coastal cities had similar but less dramatic trends, like San Diego, San Jose, Long Beach, Miami, San Francisco, Seattle, Arlington (VA) and Oakland. San Francisco is often singled out as a place where growth is not moving fast enough, yet this chart illustrates that the city is at least as willing to accept infill growth as most others.

However, looking at more recent changes -- since 1990 or 2000, for instance -- Freemark notes that population has indeed increased in the close-in areas of many cities.

The takeaway, he says, is that we need more sophisticated metrics to understand urban population shifts:

Why take these alternative measures of city growth so seriously? They should help us question whether the cities that grew fastest from 1960 to 2014 were Las Vegas, San Jose, and Austin or, alternatively, Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Miami or perhaps New York City, Chicago, and Honolulu. Each tells a different but useful tale about demographic change.

These measures might help us to understand, for example, how it is possible for half-vacant neighborhoods to exist just blocks from central Houston, which is otherwise booming. Or it may help us to understand why that city’s transit ridership has increased by just 5 percent since 1996 even though the city has grown by more than 25 percent since then. And they might help us get a better idea of what cities are truly regenerating their inner-city neighborhoods versus those that are simply gobbling up suburban growth to feed into their growing population counts.

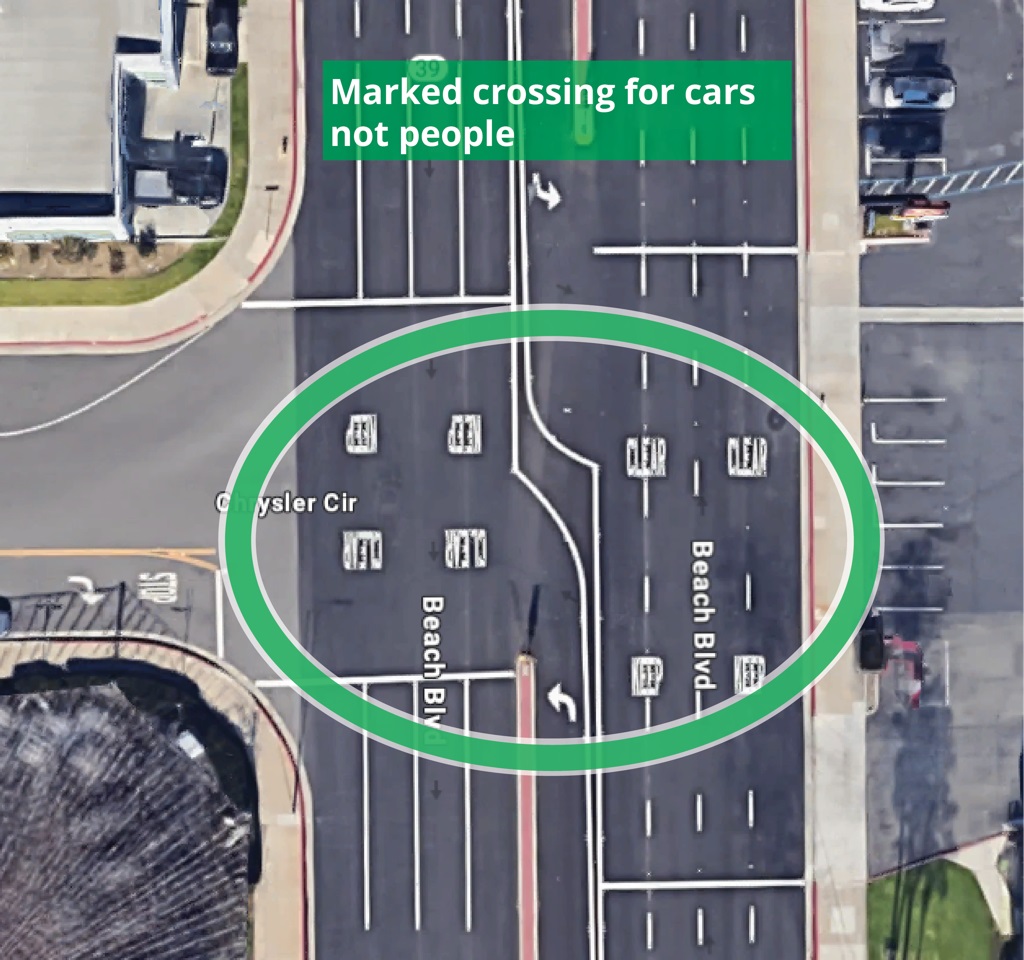

Elsewhere on the Network today: Columbus Underground explains the notorious parade float that encouraged people to run over cyclists. Washington Bikes writes up a recent court decision in Washington state that concluded cities must "maintain streets for bicycling to the same standards that apply for other traffic." And Transportation for America imagines how U.S. DOT might draw up a congestion rule that would really work.