What will it take to make sure there’s a future for lower- and middle-income people in California? Anyone who has tried to look for a place to live recently knows that question is much more than an abstract policy discussion.

Increasingly, the high cost of housing in California is driving the state’s low- and middle-income workers farther from job centers and even out of the state.

In a report released yesterday, “Perspectives on Helping Low-Income Californians Afford Housing,” Sacramento’s Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO), a nonpartisan advisory office that provides lawmakers with policy and budget analyses, tackles the sticky issue of displacement and what role, if any, new market-rate housing can play in stopping it.

It’s particularly timely, as no-growth activists in Los Angeles are currently gathering signatures to put a measure on the November ballot that would significantly hinder the city’s ability to plan for new housing growth.

"The state is facing a growing housing affordability crisis that is hurting disadvantaged and working people and must be addressed by, among other strategies, a significant increase in the production of new housing. The LAO report is their second in the last 12 months on the topic and underscores the importance of this issue," said Assemblymember Richard Bloom, who represents Assembly District 50.

The new report is a follow-up to the LAO’s report last March, which outlined the causes and consequences of California’s housing shortage, and, in short, says that given the scope of the problem, the only way to stem displacement on a large scale is to significantly increase the amount of new housing that gets built in California’s desirable coastal communities.

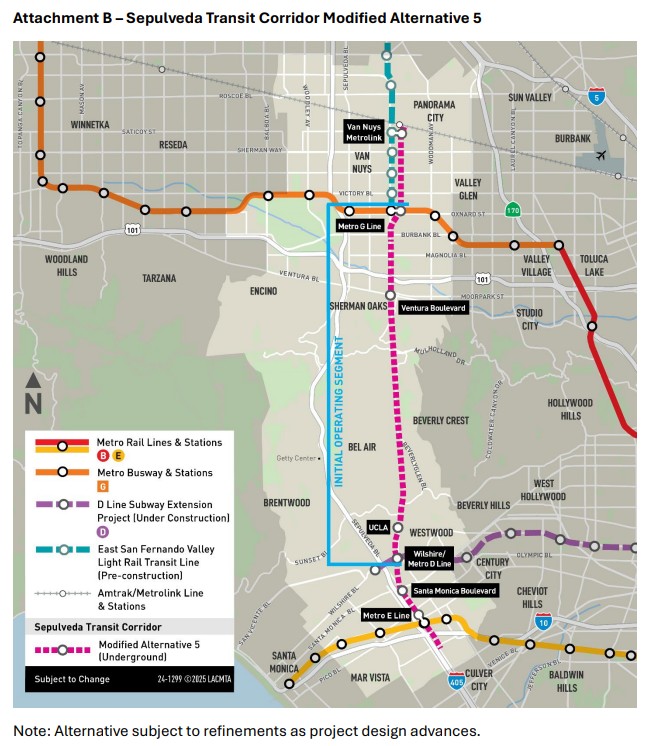

"The Legislature is poised to address this issue in the State budget and with policy proposals. As a representative of a district where the crisis is acute and as a matter of concern for all Californians, I intend to be very active on both fronts," said Bloom, whose district includes much of the westside of Los Angeles County, including Santa Monica, West Hollywood, Brentwood, and Beverly Hills.

Too great a need for the status quo

The report notes that it’s simply unrealistic to expect that current strategies to prevent displacement, like voucher and affordable housing production programs, will meet the growing need of rent-burdened low-income households by themselves.

“While affordable housing programs are vitally important to the households they assist, these programs help only a small fraction of the Californians that are struggling to cope with the state’s high housing costs. The majority of low-income households receive little or no assistance and spend more than half of their income on housing,” according to the report.

“Extending housing assistance to low-income Californians who currently do not receive it -- either through subsidies for affordable units or housing vouchers -- would require an annual funding commitment in the low tens of billions of dollars. This is roughly the magnitude of the state’s largest General Fund expenditure outside of education (Medi-Cal),” the report says.

Policies like rent control, while they may benefit some existing tenants, don’t actually do much to address the problems in the long term because price controls don’t add new housing.

“Households looking to move to California or within California would... continue to face stiff competition for limited housing, making it difficult for them to secure housing that they can afford. Requiring landlords to charge new tenants below-market rents would not eliminate this competition,” according to the report. “Households would have to compete based on factors other than how much they are willing to pay. Landlords might decide between tenants based on their income, creditworthiness, or socioeconomic status, likely to the benefit of more affluent renters.”

How does new housing help the poor?

The LAO report seeks to address the concerns of many who assume “that new construction does not increase the supply of lower-end housing” because “most new construction is targeted at higher-income households.”

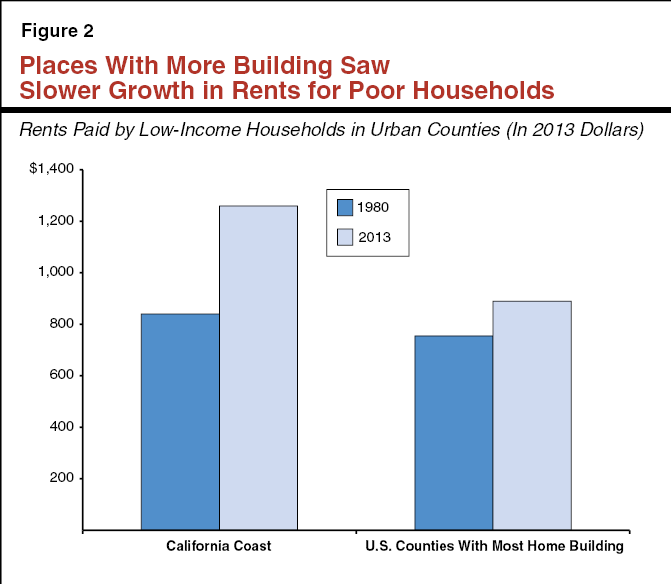

In fact, the report concludes that new construction has the overall effect of keeping rents low for existing tenants and indirectly adding to the supply of affordable housing by stemming rent growth in older buildings.

This is a point that often gets ignored when talking about housing construction: new housing gets less expensive as it gets older. Looking at a survey of housing in the Bay Area and Los Angeles, the report found that “luxury” housing dropped to the middle of the housing market after about 25 years.

But that only works if new homes are getting built.

“When new construction is abundant, middle-income households looking to upgrade the quality of their housing often move from older, more affordable housing to new housing. As these middle-income households move out of older housing it becomes available for lower-income households. This is less likely to occur in communities where new housing construction is limited,” according to the report.

The need for a wide range of building ages implies that new housing should be built where it doesn’t replace existing housing stock.

It won’t be easy

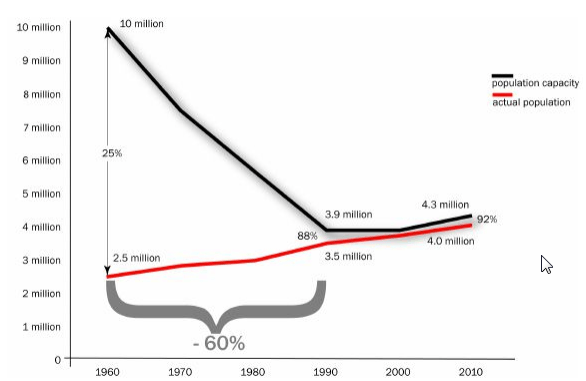

In its report last March, the LAO noted just how great the need for more housing is. In L.A. County alone, the LAO estimated that about a million more new homes should have been built since the 1980s in order to keep pace with demand.

However, political obstacles in the form of policies enacted by no- or minimal-growth leaders or initiatives severely restricted the capacity for housing growth.

This was true up and down the coast of California. But, the LAO says, it’s time to change those policies.

“The changes needed to bring about significant increases in housing construction undoubtedly will be difficult and will take many years to come to fruition. Policy makers should nonetheless consider these efforts worthwhile. In time, such an approach offers the greatest potential benefits to the most Californians,” the report says.