Los Angeles voters may once again have to go to the ballot box this November to determine the future of the city’s urban form.

No-growth activists led by AIDS Healthcare Foundation President Michael Weinstein are preparing to put an initiative on the ballot this election cycle to severely restrict most future growth throughout the city. The so-called “Neighborhood Integrity Initiative,” which comes at a time when the region is experiencing a historic housing shortage, would short-circuit Los Angeles’ (albeit imperfect) effort to reshape itself along a growing network of high-quality transit corridors, bike lanes, and walkable streets.

In short, the proposed initiative, which would need the signatures of about 60,000 registered Los Angeles voters to qualify to be on the ballot, asks voters to double down on a static vision of Los Angeles as a sprawling, auto-centric mega-cluster of suburbs.

As the initiative moves forward, Streetsblog L.A. hopes to explore how the proposal would impact the city’s ability to address the major livability issues facing us today, including the regional housing shortage, income segregation, and an urban form that favors cars over other modes of transportation.

A plan to ban planning

The initiative, which specifically aims to end, among other things, the practice of amending the city’s general plan to allow specific projects to be built, does have a grain of truth in its rhetoric, said Mott Smith, principal at Civic Enterprise Development and Council of Infill Builders board member.

“The grain of truth is that we don’t follow our plans,” Smith said. “But we have this outdated style of planning. We’ve built this really complex system of workarounds.”

It is those “workarounds” that allow projects to be taller and denser than the general plan otherwise allows.

“This initiative actually bans planning. What it says is that you can never adopt a plan that substantially changes the density or height of a neighborhood,” he said.

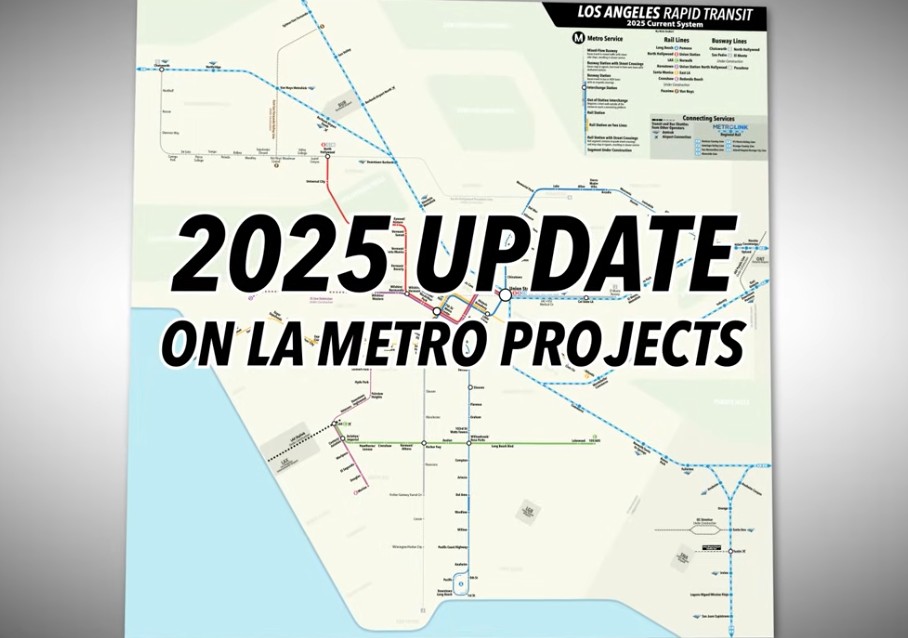

But L.A. is changing. A growing rail transit network and an increasing demand for walkable, bikeable streets mean that the urban form has to change, if we hope to break free of the car-centric model of planning that has reigned in previous decades.

It would also certainly make it impossible for Mayor Eric Garcetti to reach his goal of alleviating rising rents caused by a major housing shortage in Los Angeles by allowing for the addition of 100,000 new homes by 2021.

“What this initiative would do is ban any future plans that allow for neighborhoods to evolve. This would lock the entire city amber as it is today,” Smith said.

That flies in the face of “AB 32, SB 375, every piece of state policy that says we need to densify our urban cores, create more walkability,” he said.

Do we really need more parking?

Driving home the point that the initiative’s supporters believe the future of L.A., like the recent past, belongs to the cars is the fact that the initiative includes language that would actually increase on-site parking requirements.

The initiative says that “under no circumstances may the required on-site parking be reduced by more than one-third (including by remote off-site parking) from the number of spaces otherwise required to be provided by any other applicable provisions of the Los Angeles Municipal Code.”

Again, the lack of flexibility doesn’t take into account that going forward, we want to encourage people to get to their destination by means other than just driving. Suburban levels of parking drive up the cost of housing as well as incentivize more people to drive to their destination, adding vehicle traffic to our streets. This blanket provision is actually tremendously counterproductive for new buildings near high-quality transit, where studies have shown that the availability of parking has a significant impact on whether or not residents will take transit.

Whose city is this, anyway?

When ex-mayor Richard Riordan endorsed the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative, he claimed that current Garcetti was like a member of the Tea Party and that he was only helping the rich get richer.

Putting aside the irony that in many places around the country, it is the Tea Party that is actively opposing sustainable urban growth, the rich are actually getting richer in Los Angeles and it has to do with zoning, but not in the way Riordan means.

Los Angeles is one of the most economically segregated cities in the country and it is directly related to how restrictive -- not permissive -- zoning is.

That point was made clear when Robin Hughes, president of the nonprofit Abode Communities, recently told The L.A. Times that her organization regularly asks for zoning changes or amendments to the city’s general plan, when it builds housing for low-income families and formerly homeless people. The initiative would make that practice impossible.

A recent study out of UCLA by Michael Lens and Paavo Monkkonen demonstrated that, in fact, the more zoning a city has, the more geographically segregated the wealthy and upper-middle class are from lower-income residents.

L.A. has been heading in this direction as a result of widespread downzoning in the 1980s and 1990s that saw L.A.’s planned potential population capacity shrink from about 10 million people to about 4 million people.

The result of ballot initiatives like Prop U, which severely restricted growth on L.A.’s commercial boulevards, is an increasing gulf between the rich and the poor in Los Angeles.

“This ballot measure is more of that,” said Monkonnen, referring to the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative.

“It punishes younger people and people who are new to the city,” Monkonnen said. By opposing change in the built environment, anti-growth activists are saying, “We don’t want different kinds of people living here.”