Moreno's perspective is one I've written about many times while tracking changes in this lower-income and largely Mexican-American community over the last few years, most recently with regard to developments Metro had planned for a complete overhaul of Mariachi Plaza.

And it's a perspective readers from outside the community often find controversial, associating it with "anti"-ness: anti-outsider, anti-white people, anti-change, and/or anti-development. Or they see it as a NIMBYist position that denies Boyle Heights' own storied history of being a haven for people of many different ethnicities, including Caucasians.

Ever the occasional optimist, I like to think that more knowledge about the history of the community could help remedy this disconnect.

Because when you know the history of how Boyle Heights came to be -- how the institutionalization of racism in city planning and policy via redlining, government-sponsored white flight, "sanitation" sweeps, urban renewal programs that razed housing and funded freeway construction aimed at displacing and isolating poor ethnic communities, overt discrimination in education, the denial of economic opportunity, the labeling of non-white cultures as subversive, immigration raids, police brutality, and deliberate disinvestment constrained Boyle Heights' ability to flourish -- it becomes very easy to understand why the existing residents are raising questions about race, class, and the intentions of both public and private investors in the community.

And knowing how the community managed to thrive in the face of these obstacles and take pride in the heritage they were once told rendered them "unteachable" and "mentally inferior" makes it easier to grasp what it is that residents like Moreno are looking to preserve and invest in. Rather than "re-imagining," "revitalizing," or "place-making" their community, as is popular in planning now, they seek to help Boyle Heights grow and develop while remaining true to what they believe it represents. And what it represents is community, culture, resistance and resilience, unique voices and forms of artistic expression, struggle, transcendence, family, and heritage. The physical landscape matters, in other words, but it is the people, their histories, and their relationships with each other that give it meaning.

These are all things that I've tried to convey in previous articles in one form or another. But it's one thing to read descriptions of how a community feels about itself and another altogether to see it for yourself. Which is probably why the arrival of Betsy Kalin's East L.A. Interchange feels rather timely.

Eight years in the making, it began as the Connecticut-born Kalin's exploration of what made Boyle Heights a place that people were proud to be from and felt rooted in, even long after having moved away.

Early on in the process, her focus was on residents' transcendence of racial boundaries to forge a strong sense of community and enduring friendships in an era when state-imposed segregation was the order of the day. To that end, we hear from a range of elder African-American, Japanese, and Jewish Angelenos (and, occasionally, will.i.am) that grew up in the area in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s and have memories of the days when Boyle Heights was a veritable United Nations of neighborhoods and everyone knew a little bit of everyone else's language.

Cognizant that it is hard to speak about the history of the community without investigating the discriminatory policies that gave rise to it, however, Kalin seems to have shifted gears a bit. While still (a little too) driven by the narrative of multi-ethnic harmony, the film also incorporates the voices of experts like George Sanchez, Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity and History at USC, to illuminate those links.

It was the right choice.

The history Kalin puts on the screen is engaging and important, and peppered with lots of old photos, archival footage, and narrations by Danny Trejo.

While I really enjoyed the meticulousness with which the film explored Boyle Heights' early years, I do wish it had given the same level of attention to the Mexican-American experience from 1968 onward. The fact that it does not, and that Latinos are not that present in a film about a community that is now well over 90 percent Latino, are significant shortcomings. The oversight is all the more glaring because, at this very moment, the community is asking itself how the identity born out of the struggles of that era can be used to inform and guide development and change in the area.

This oversight may be due to funding issues -- Kalin struggled to raise funds for several years. Or it could be because the film's original mission of exploring multi-ethnic harmony had been accomplished by then. Perhaps it was a bit of both. Either way, the jump from decade to decade in the last quarter of the film makes it feel hurried and somewhat disjointed. And questions raised about how the Gold Line will impact the area make it feel a bit outdated, given that the train arrived in 2009 and an entirely new set of challenges have arisen since then.

Those concerns aside, I genuinely enjoyed the film and recommend it to anyone interested in learning about Boyle Heights and the history of segregation in Los Angeles. I detail some of the history seen in the film below, discuss why focusing on just the harmony within the community is problematic, and conclude with what Boyle Heights' past might mean for its future.

"No Place for Upstanding Citizens..."

At the turn of the twentieth century, Sanchez and other experts explain in the film, restrictive racial covenants meant that non-whites (which, at the time, also included Jews, Italians, the Irish, and Russians) were limited to living in the city's least desirable locations. Located across the river, lacking many of the amenities and services white communities had, and already populated with African-Americans that had fled the South, Russian Molokans that had fled religious persecution, Jewish and Italian immigrants fleeing World War I, Japanese migrants looking to start over after the San Francisco earthquake, and Mexican immigrants that had fled the turmoil of revolution in Mexico, Boyle Heights fit that bill.

As waves of migrants and immigrants arrived in the 1930s and '40s and Boyle Heights swelled in population and diversity, the white establishment became both increasingly suspicious of the community and eager to contain it. This was most explicitly seen in the mass incarceration of Japanese and Japanese-American residents during World War II, when one-third of Roosevelt High School's student body simply disappeared from the rolls in 1942.

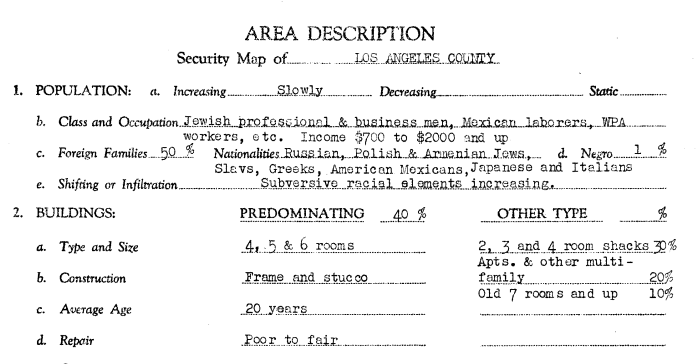

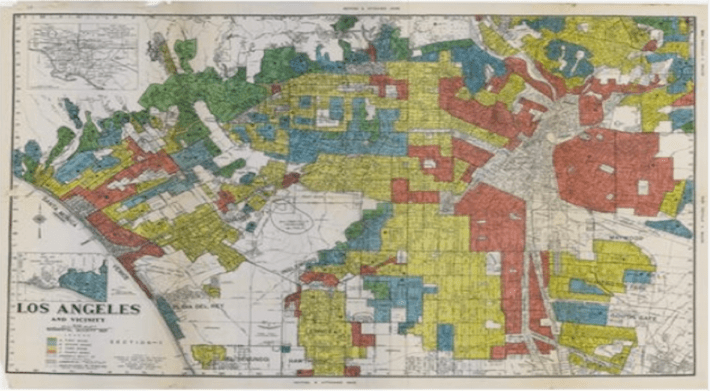

But it was redlining, Sanchez and others explain, that played one of the more significant roles in isolating Boyle Heights and setting the stage for the economic and social struggles that would dog the community through the present day.

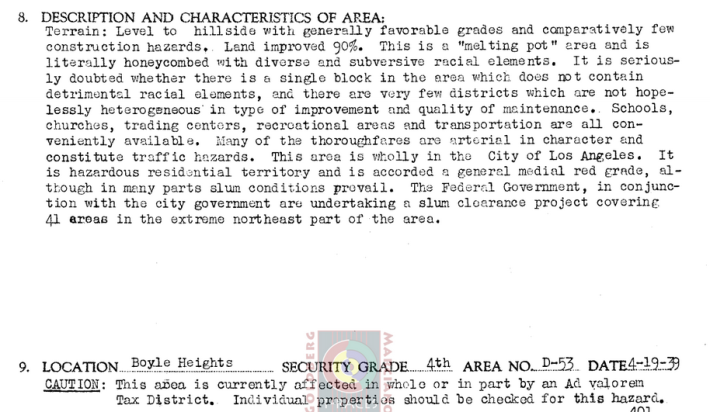

In 1939, the federally-sponsored Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) described the neighborhood as “hazardous residential territory” with “diverse,” “subversive,” and “detrimental racial elements” lurking on every block. As such, it accorded the area a “red grade,” signalling to private banks, real estate agents, and mortgage lenders that this was “no place for upstanding citizens to purchase a home or get an easy loan.”

The impact of redlining was devastating and enduring.

Not only did it make it too costly for Boyle Heights residents to become homeowners in the area, it simultaneously subsidized both sprawl and white flight.

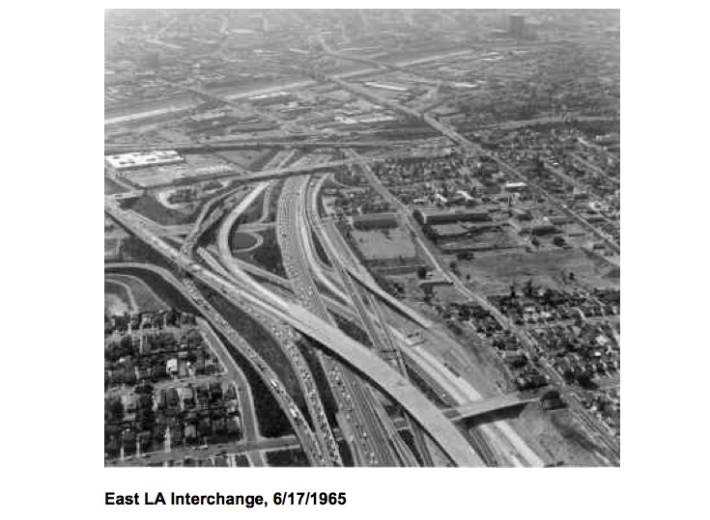

As soldiers came back from the war and sought to purchase homes with their pensions, Sanchez explains, they were funneled toward high-rated places like the San Fernando Valley. Once inconvenient to reach, these suburban areas were made more easily accessible thanks to the Urban Land Institute's recommendations that a tangle of seven freeways be built right through the flats of Boyle Heights.

The construction that began in 1944 and lasted through 1972 “cleared wide urban gashes" through ethnic "slums," demolishing approximately 2000 homes and displacing as many as 15,000 people in the process. (For more, see here.) Land was seized by eminent domain and evicted residents and landowners were given very little compensation in return.

Making a brief appearance in the film, City Councilmember José Huizar affirms that Boyle Heights paid a steep price for this approach to progress.

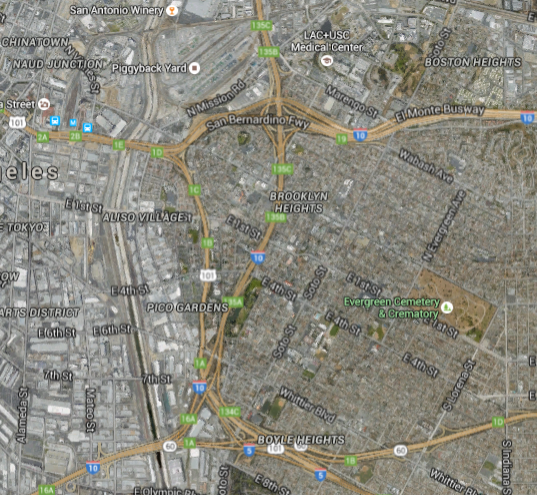

Not only would the community be almost entirely encircled and divided up by ribbons of freeways (below), but the pollution generated by the approximately 874 million vehicles that traverse the interchange every year would gift generations of its residents with respiratory and other health issues.

The freeways, deterioration of the housing in the area, overcrowding, and stigma attached to being from Boyle Heights, Jewish Historian and former resident Harriet Rochlin explains in the film, meant that, when opportunities arose for members of some ethnic groups to migrate to other areas of town, they jumped at the chance.

For many, that moment came when the second wave of the Great Migration of African-Americans hit the West Coast in the post-war period.

Faced with a rapidly-growing minority population, the white establishment decided to reconsider its definitions of “whiteness” and warily welcomed Jews and other European immigrants under the now more forgiving label. The shift granted Jews the freedom to join the newly-arrived community of Jews growing in prominence on the Westside, some of whom were developers hoping to attract other Jews to the new housing they built.

Warm ties remained between some of the Jews and the Latino community, even after they had left -- Jewish organizations helped fund the massive voter mobilization effort that saw Edward Roybal elected to the City Council in 1949.

But the solidarity felt within the multi-cultural coalition that worked so tirelessly to elect the first Mexican-American to serve on the council since 1887 (effectively described by his daughter and U.S. Representative Lucille Roybal-Allard), wasn't enough to keep those groups in Boyle Heights.

By the late 1960s and early '70s, only four percent of L.A.'s Jewish population remained. Other newly-white residents continued to move west while the African-American and Asian populations dwindled. Only the Latino population of the area -- now at 80 percent -- continued to climb.

Urban Renewal and the Flipside of Harmony

Unfortunately, it is at this pivotal moment -- the very moment that Boyle Heights becomes more ethnically homogeneous, a strong Chicano movement emerges to struggle for civil rights, and the community wages the battles depicted on so many of its walls -- that the documentary loses some steam.

The care with which the early history was addressed gives way to a bit of hop-scotching through the next several decades. The 1968 Blowouts, immigration raids, police brutality, the rise of gangs in the late '70s and the "decade of death" (as Homeboys Founder Father Greg Boyle refers to the period of intense gang violence between 1988 and 1998), and the threat of gentrification are all touched upon, but not explored in-depth. It leaves the viewer with only superficial insights into who the current residents are as a people.

Similarly, while Kalin's interest in upending negative stereotypes that paint Boyle Heights as a violent place (aptly illustrated with a clip from Anderson Cooper's 2005 report on the "Gangs of Hollenbeck") is laudable, the snapshot offered of gangs leaves viewers with the impression that they are an aberration and possibly linked to the influx of Mexican-Americans, neither of which is really true.

Instead, in many ways, the gangs are a direct response to the insecurity created by many of the same discriminatory policies and practices that shaped the positive, multi-ethnic development of Boyle Heights. In fact, gangs had been a part of the landscape in some areas of Boyle Heights since the 1920s and '30s. As waves of migration brought newcomers and, with them, insecurity and economic disparity, residents of all creeds organized to reinforce their claims to particular territories and defend them against both newcomers and incursions by law enforcement.

This cycle reached new heights in the 1950s and '60s with the federal Urban Renewal Program which, in theory, aspired to eliminate substandard housing, construct adequate new housing, reduce segregation, and revitalize urban economies around the country. In practice, thousands of homes in ethnic enclaves were declared unsanitary slums, acquired via eminent domain, and promptly demolished. The land was then often sold at below-market rates to private developers who cared very little about the needs of the poor, responding instead to government incentives to construct commercial buildings and housing for the well-to-do.

Even more troubling was that the $100 million Los Angeles received from the program only provided housing for 10,000 of the 48,000 families that had been uprooted. As families displaced by both the Urban Renewal Program and the construction of the East L.A. Interchange crowded into already over-crowded neighborhoods, new gangs evolved to establish new social infrastructure and defend themselves against the existing gangs. The construction of public housing in the 1960s failed to alleviate these issues. Instead, because the projects were essentially artificial communities, physically isolated from the commercial and cultural cores of the community and restricted in their ability to host visitors, residents placed there had to create their own social infrastructure from scratch. Gangs quickly emerged to fill that void as well as to provide the security that law enforcement did not.

The city's prolonged neglect of the community, disregard for deteriorating conditions, disruption of the social infrastructure, and efforts at suppression that fed gang development then are some of the same factors that feed those gangs that run in the community now.

Interestingly, this reality doesn't make the harmonious relationships Kalin uncovered in her documentary any less true. Nor does it make Boyle Heights any less special than she, I, and anyone else that loves the community believe it to be. It just suggests that the discriminatory policies that the community members in the film had worked so hard to transcend also exacted a tremendous toll on Boyle Heights' most vulnerable residents. And the failure of the city to make any real investments in alleviating the disenfranchisement felt by those residents or that of subsequent generations, means the legacy of those early segregationist policies continues to live on in L.A.'s more troubled streets.

Fears of Displacement, Disruption of Social Fabric Loom Large

I raise all this because current patterns of growth, change, and displacement across Los Angeles have a similar potential to disrupt the social infrastructure in lower-income communities of color.

For a community where that infrastructure has been so vital to residents' ability to transcend discrimination, disenfranchisement, disinvestment, environmental degradation, and denial of economic opportunity, the prospect of seeing it disrupted by displacement is deeply unsettling.

But the unique strength of that social infrastructure, for some, is also a source of hope.

"We made [Boyle Heights] what it is," Xavi Moreno said in a recent conversation. "We didn't have a choice."

As a result, "we lack things," he said, referring to the absence of name-brand shops, entertainment venues, and the amenities seen in well-to-do neighborhoods. "But we [also] don't."

The richness of the community, he continued, lay in its people and their connection to place and each other. Amplifying those connections via ongoing conversations about Boyle Heights' history, what it means to people, and what its future should be, he said, will give the community a sense of ownership and help them grow together.

"It isn't about how we stop gentrification," he said, acknowledging that a strong community spirit is not much of a match against rising rents and ongoing property acquisition by developers, "but how we transform it."

"Like my friend, brother, and barrio mentor Nico [Avina] says," he said, "'The possibilities are endless.'"

Check out "East L.A. Interchange" at the New Urbanism Film Festival. The film plays opening night, October 8, at 8 p.m. at the ACME Theater (135 N. La Brea Ave.). Schedule and program are found here.