"What do we want? Safe streets! When do we want them? NOW!"

So went the chants as approximately 40 members of the South Central community headed north toward City Councilmember Curren Price's constituent center on Central Avenue yesterday evening.

They were headed there to speak with the group of stakeholders that recently got the green light to initiate a ballot process for the formation of a Business Improvement District (BID). The marchers were eager to register their concerns regarding the councilmember's effort to have the Central Ave. bike lane excluded from Great Streets' plans for the section of Central between Vernon and Adams and removed altogether from the larger Mobility Plan 2035, which envisions a protected bike lane running the 7.2 miles from Watts to Little Tokyo.

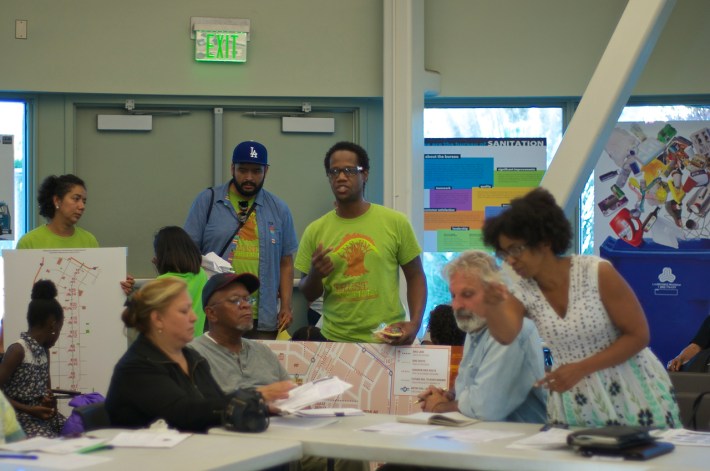

Addressing the meeting attendees, Malcolm Harris, Director of Programs and Organizing at TRUST South L.A., gestured toward the crowd that had piled into the conference room and said, "Our constituents here want to have safer streets...[and] we want there to be engagement around this issue before any [city council] motion is taken out."

Organizers of the BID received the testimony but reiterated that, as they were still in the process of formation, they had very little power to do anything other than listen to the community's concerns and ensure they were incorporated into efforts to build consensus around the future form of Central Avenue.

Given residents' frustration that so much of the planning for the street had already happened behind doors that even the prospective BID members had been shut out of, it wasn't the cathartic moment they were hoping for. But news that next month's meeting would entail more hands-on engagement with the design of Great Streets project slated for the street (below), many resolved to come back and participate.

Then, just as suddenly as they had arrived, the marchers headed back out into the streets to hold a press conference at the intersection of Vernon and Central.

Those that took the megaphone to speak on the corner of Vernon and Central had ties to South L.A. advocacy organizations TRUST South L.A, Community Health Councils, and Ride On! bike co-op, but all were residents in the area and regular users of the street. And, for most, a bicycle was their primary form of transportation.

For Nancy Flores, who grew up in the area and now had two small children, safety was key. To get around and shop for her family, she said, she had to ride a bike every day. "We, as cyclists, also have a right to be on the streets," she said, and a bike lane would slow the street down and make it safer for everyone.

For Maria Almeida (above), who has rigged her bike so the youngest child can ride in a crossbar saddle in front and the second youngest can ride on the back (see photo here), safety was also an issue. Not owning a car but needing to take her kids with her to visit the markets and clinics on Central, she started training them to ride with her when the youngest turned two.

People are surprised to see me, she said in Spanish. They ask, 'How is it that [the kids] behave so well?'" [don't goof around or fall off].

Spending as much time as they did in transit on the bike, it seems, the kids had absorbed the danger that the streets presented and understood that they had to behave and hang on tight.

Frustrated that training her kids still wasn't nearly enough to keep them safe, she called on drivers to be allies to cyclists.

"...Que se unan a nosotros y que nos apoyan," she said. "Porque los carros no nos respetan." [I hope that they ally themselves with us and support us, because [right now] cars do not respect us.]

For Araceli Alvarado (above), riding with her kids had not gone so well. Back when her son was in middle school, he had been hit by a car making a right turn and dragged a short distance. Now in his late teens and headed for community college, he is finally interested in taking up cycling again to get back and forth to class, but she is nervous about letting him ride. And her 10-year-old daughter rejected cycling outright after trying it once.

"She gave the bike away [almost immediately]," said Alvarado. She was too intimidated by the crush of traffic along the avenue.

"What is the point of me feeding good food [to them] if they can't also get exercise?" Alvarado asked. For her family, and by extension, the larger community to be healthy, she felt, one without the other wasn't going to do much good.

Central needed a bike lane, she reiterated, because "most people use this street to bike. They need this street."

The importance of Central was something many of the residents I spoke with alluded to.

Andres Ramirez-Huiztek of Community Health Councils said a slower street would both save lives and give people the chance to appreciate Central Avenue. Such a historic street deserved that. Adé Neff, founder of the Ride On! bike co-op, spoke about his reliance on a bike for transportation and the need for infrastructure on Central.

"It's a main artery; everybody uses it. We want people to slow down...and appreciate the businesses."

Noticing that by having gathered on the corner of Vernon, the group of residents was inadvertently pushing sidewalk cyclists into the street, Will Holloway, CEO and founder of the South L.A. Real Rydaz, said, "Now, that's why it is important to get these [bike] lanes in here."

Forcing pedestrians and cyclists to share a sidewalk made things uncomfortable for everyone and clearly wasn't doing much for the business environment.

Besides, Holloway argued, the streets were wide enough for bikes: "They've got enough room!"

It was the trucks that needed to move, not the cyclists.

"These streets aren't built for big rigs," he said, describing the struggle of trucks to make turns and the way they "tear up the streets" and destroy the asphalt.

For Darryl Johnson (Unique Riders), Tyrone "T-Money" Williams (Real Rydaz), and Henry Jackson (Real Rydaz), a bike lane would give cyclists the protection that the 3-foot passing rule (law that drivers must give three feet of space when passing them) was not.

"Drivers need to be more cautious," said Jackson, shaking his head. "They don't give you the three feet."

Williams agreed, saying, "You shouldn't have to be riding in fear like that." Getting a ticket for sidewalk riding at night had been a regular thing at one time, he said. Meaning that cyclists felt pressured to be in the street. And, as all three agreed, many side streets were still off-limits to riders -- even those that wanted nothing to do with gangs and had no problem getting along with everybody. Leaving most lower-income cyclists no choice but to use busy arterial streets like Central or Gage.

"We just want [drivers] to be more mindful," concluded Johnson.

While riding to the gathering on Central yesterday afternoon, I was horrified to see young men stop to scoop up an indigent cyclist that they had knocked down with their car and carry him over to the sidewalk.

To symbolize the very real cost cyclists pay for their vulnerability, Danny Gamboa (Ghost Bike Documentary) and Samuel Bankhead put a ghost bike up at the corner of Central and Vernon.

The struggle for equitable transportation infrastructure in lower-income communities is real and it is urgent.

Whether the councilmember or the Mayor's Office -- which oversees the Great Streets program -- will hear these concerns and be responsive to them remains to be seen.

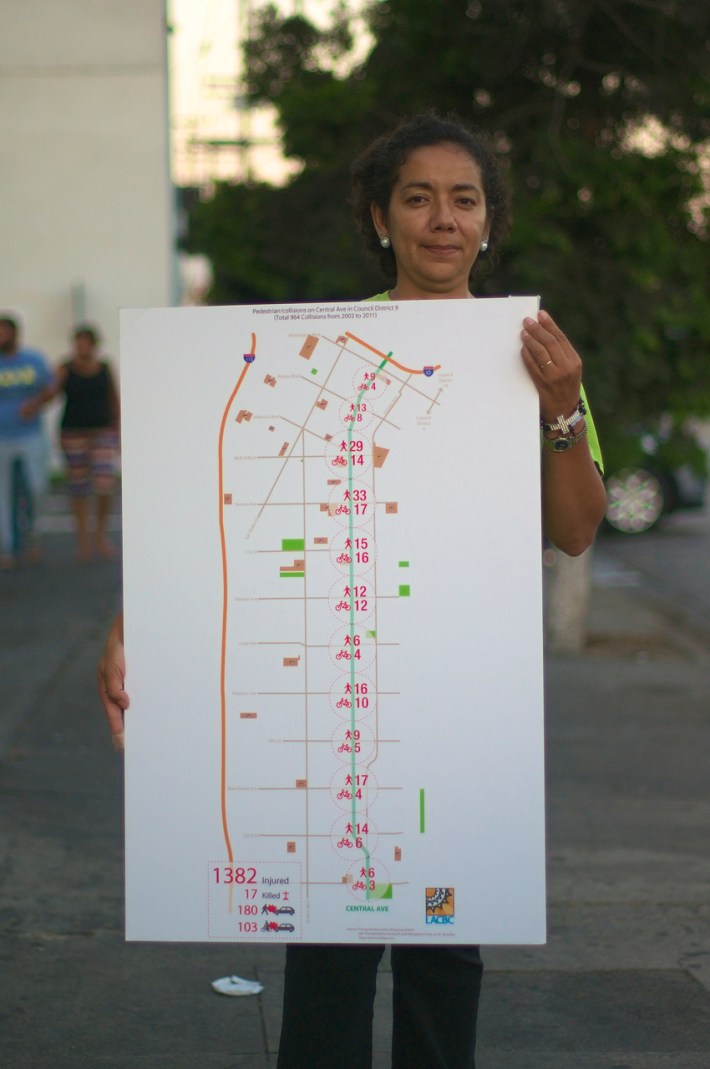

Given all the fanfare surrounding both the signing of the Vision Zero directive (the effort to reduce traffic deaths to zero by the year 2025) and the approval of the Mobility Plan 2035 (the effort to transform the way Angelenos get around their fair city) last month, one would expect it to be easier for a community with so many high-injury arterials to get the ear of elected officials.

But it also would not be the first time that politics got in the way of safety. Nor would it be the first time that the needs of lower-income communities were ignored.