We here at Streetsblog have been known to complain about the state of Los Angeles' transportation infrastructure from time to time.

And while it is true that we do have a ways to go in making the streets more hospitable to those that do not travel by private automobile, I am often reminded that we've got it pretty good here, comparatively speaking.

In my previous life as an academic, I spent quite a bit of time traveling in remote areas of developing countries where the obstacles to mobility also constituted major obstacles to economic development, growth, and pretty much everything else you can think of -- health, education, communication, relationships, proper governance, and access to resources.

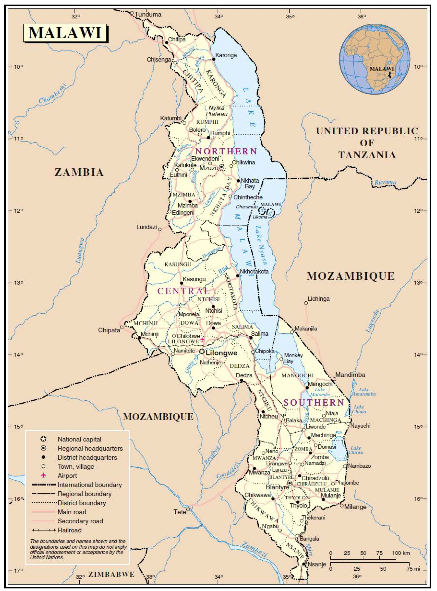

Nowhere did this seem clearer to me than in Malawi, also known (deservedly so) as the "Warm Heart of Africa," an East African nation of about 16 million people.

During the three summers I spent doing research on international development aid organizations there, I did my best to travel as the locals did. Which meant that I spent a great deal of time on foot.

I made the choice, in part, because my research budget was quite small, private transport could be exorbitantly expensive, and "public" transit was not always reliable.

This was especially true when I was last there, in 2011, and petrol was in extremely short supply.

The shortage hit the economy hard. People lost entire days waiting at filling stations, hoping rumors about the arrival of fuel shipments would not prove baseless. And it slowed agricultural production by causing a decrease in the distribution of fertilizer (via the government subsidy program) and limiting the ability of farmers to get products to markets or mill their maize.

It also sent transportation prices through the roof -- a 10-minute taxi ride across town could cost more than 2,000 Malawi Kwacha (about $5, or almost a week and a half's pay at minimum wage, for a Malawian). And it drastically reduced the ability of people to access transit, as minibuses -- the privately-owned vans that serve as public transportation -- struggled to keep their vehicles topped off with fuel and on normal schedules.

A trip into the capital from an outlying district that normally took an hour and a half now took several hours.

If you were lucky.

It was not unheard of for minibuses traveling long distances to stop well short of destinations, stranding passengers. In such cases, either they had run out of fuel or didn't want to get stuck at a remote market where they knew fuel was even more scarce. Others drivers got creative with their fuel conservation methods, cutting off the motor to coast down hills or driving one leg of the route and coordinating with other drivers to pack any remaining travelers into more efficient (but often highly questionable) passenger cars for the final legs.

These issues aside, I preferred to walk because I believed that it would be the best way to get to know the place and its people.

This turned out to be even truer than I expected.

Because it was such an anomaly to see a Westerner walking anywhere, people took it upon themselves to either walk with me or track my comings and goings and engage me in lengthy conversations. Those conversations did more to help me understand Malawi's daily rhythms and the struggles of its citizens from their perspective (which generally differed tremendously from that offered by aid organizations) than any of the formal interviews I conducted.

Walking also gave me incredible insight into just how much time and energy the poorer members of society lose trying to get themselves from place to place and just how hard it is for them to do so safely.

Walking and cycling are almost exclusively the purview of the Black African population -- especially the farmers, rural women, vendors, the working class, and the desperately poor.

For the South Asian/Middle Eastern/Arab community -- the well-to-do business class -- the aversion to walking or cycling seemed to be linked to issues of status. Many saw themselves as both distinct from and above the native population, and preferred not to walk, cycle, or use the minibuses as modes of transit.

As a mode of transit, walking seemed to be particularly problematic for women of that community, I soon found, as men (recognizing me as Western but also potentially of Indian heritage) regularly stopped and demanded I get off of the streets and into their cars. The demands were also often accompanied by marriage proposals as many of the men weren't keen on marrying local, either (See the recent stir caused by an interracial marriage in Kenya).

Oddly, members of the white expat community -- most of whom were in the country doing aid work -- also regularly stopped to offer me rides. Ignoring women carrying more than one child and/or burdened with enormous bundles of goods on their heads, they would pull over and cheerily ask a relatively unburdened me where I was headed and if I needed help.

The assumption seemed to be I was one of their clan. Or they may have just been surprised to see me -- outside of tourist areas, Westerners tended to be a rare sight in the streets.

The reasons for this were many.

Some seemed not to consider walking or biking as a transit option, since it generally wasn't something Westerners did (at least, in the locations where I was). Others seemed to prefer the buffer the car offered from locals who might see them as having access to money or jobs. And cars were necessary at night, when unlit streets were deserted and pedestrians were vulnerable to attack.

But most Westerners also seemed to favor private vehicles because distances could be great and the utter lack of safety on the busy streets of the capital, the lack of infrastructure in the rural areas, a lack of faith in drivers (many are unlicensed, do not maintain their vehicles, and alcohol can be a problem), and the discomfort of pounding polluted pathways in the heat or rain conspired to make bicycling and walking wholly unappealing.

Their concerns about safety were certainly nothing to sneeze at.

Despite the fact that the vast majority of Malawians are pedestrians, designated sidewalks along the roadways -- even in the capital -- are a recent innovation. Pedestrians often must rely on the shoulders, if they want to walk along many of the paved roadways (below).

And, I soon found, pedestrians and cyclists never have the right of way. If a vehicle wants to turn right and you're moving through the intersection, you'd best get out of the way.

Newer roads might have more shoulder (below), but still lacked any real protection for people from speeding vehicles.

The fact that much of the housing for the working classes in the capital and surrounding towns is connected only by dirt roads and footpaths (below) means that the poor often have to walk long distances to a main road to reach minibus stops.

It also means that, this time of year, when sunset is around 5:30 p.m., you're likely to see a panicked commute undertaken by those desperate to get home before dark.

Because there is little in the way of street lighting outside the developed areas of city centers and people don't feel safe being out after dark, minibus stops are more chaotic than than usual, bike taxis (some of the drivers are below) are in high demand, and those who either can't afford to wait for a minibus or bike taxi or afford to pay for them, can be found power walking or even jogging their way home.

During the rainy season, passage to and from those areas becomes even more time-consuming. Flash flooding can make paved roadways a mess and turn even the most firmly packed dirt roadways and paths into slippery and unsanitary mudways.

In rural areas, where distances are much, much greater, the one or two paved roads connecting many of the districts are often the easiest and most direct routes for people to take to the market centers to buy and sell goods.

These two-lane roads are generally quite narrow, however, and it can be very uncomfortable for pedestrians, animal-driven carts, or cyclists to move along their shoulders as heavily-laden transport trucks rumble by.

People heading to market often do so in the early morning hours along the shoulders of unlit highways, precariously balanced with heavy goods.

Men may load anywhere between 50-100 kilos of grain onto the back of their pushbikes while women may carry large loads of wood or other goods on their heads.

Or, a bike taxi driver may have someone carrying heavy goods or a mother and a couple of her kids balanced on the back of his bike.

A fast-moving trailer truck veering too close can topple them, possibly damaging the goods, the bikes, and/or the people in the process.

Horrific casualties along those highways are not unusual.

In Mchinji boma (the center of the district), the dirt roads around the market and throughout the neighborhoods were in fairly good condition.

With well-packed dirt and minor dips and bumps, most were rather easy to walk or ride a bike along (at least, when dry).

In remote rural areas, however, sandy narrow footpaths serve as the gateways to other villages, fuel foraging sites, water wells, farmers' fields, and the larger dirt roads that lead to the bigger markets.

The more remote those dirt roads were, the poorer their condition seemed to be, as a general rule, and they were often populated with makeshift structures villagers had built over washes.

In the dry season, they are uncomfortable to pass in a vehicle and exhausting if you are pushing 50 kilos of grain on a bike for any significant distance. In the rainy season, they can become treacherous and bridges like the one below often get completely washed out, making passage to villagers' fields or the world beyond quite difficult, if not impossible.

All of which you might be able to withstand if you are healthy, have food stored up, and don't have business elsewhere. But if you have a pregnant woman in the back of your bicycle ambulance that you are trying to get to a clinic in a major trading center, for example, it can be very problematic. (See a washed out dirt road, here, and evidence that the paved roads are not always that much better, here)

As I write this, I realize that none of this makes Malawi sound particularly appealing. Which is unfortunate -- it's a genuinely wonderful place, full of wonderful, kind, warm, and amazing people. I loved being there and I often miss it.

But it is striking to be confronted with the extent to which something as basic as mobility can consume so much of the productive time of those who struggle the most. When people lose days trying to get back and forth to health clinics or markets, or can't get to markets at all, in the case of women who might struggle to carry both their children and a load of goods over long distances, it is easy to see how important infrastructure and mobility solutions are for those on the margins.

These aren't the only needs of the poor by a long shot, of course, but they certainly are significant.

What is also striking is the resilience of people in dealing with the obstacles they face. I don't say that to romanticize poverty -- I can assure you, it is not romantic. Even in remote areas, people I met have a sense of how far behind Malawi is with regard to development, and they want better for themselves and their children. But it doesn't mean that the people don't possess a tremendous strength and an ability to navigate challenges that would probably knock most of us out. So, just to end the story on a more positive note, I will leave you with snapshots of some of the people I met on my last trip:

- The bike taxi drivers, who somehow always managed to get the job done, despite lacking access to bike parts, tools for repairs, proper footwear (many rode in sandals), or a reliable income.

- The minibus drivers who, like the bike taxi drivers, keep the country moving, both literally and figuratively, and usually with relatively good humor (if not the best taste in music --Reggaeton was all the rage when I was there last).

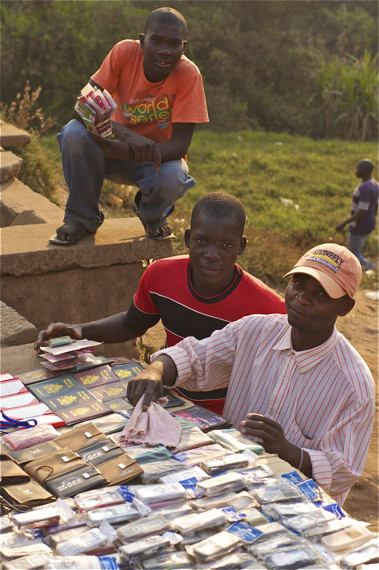

- The vendors who hustle relentlessly because they know many of their customers -- farmers -- only have disposable income during a few times of the year. And now, as cheap Chinese goods are flooding the market, they're finding themselves competing against shops stocked with affordable new goods (albeit of incredibly poor quality that often fall apart soon after purchase).

- The women who, while not always as visible in rural markets or urban economic street life (although increasingly so, in professional life), are the glue that keep families together, particularly in rural communities, where they may shoulder both the farm work and caring for the household.

- And the women, like Mrs. Anderson (proprietress of the inn I stayed at in Mchinji, below) who work to give women a voice while keeping Ngoni tradition alive.