What do someone's shoes tell us about them?

Some would argue quite a bit.

Others would argue that you need to actually spend some time inhabiting someone else's shoes in order to really understand who they are and the journey they've been on.

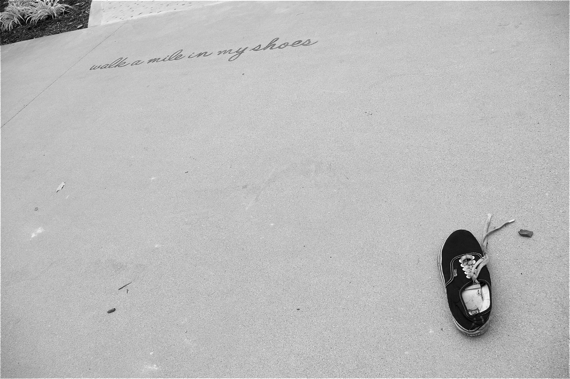

Kim Abeles, the artist behind the "Walk a Mile in My Shoes" public art installations at Jefferson Blvd./Rodeo Rd. and Rodeo Rd./Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., seems to believe both are true.

Inspired by "the wish to walk in the footsteps of Martin Luther King, Jr. and those who walked in solidarity for the civil rights movement" as a way to know them and their struggles, she began looking for a photograph of King's shoes.

Instead, she came a cross "a profound collection of shoes belonging to members of the peace marches" that had been collected by Xernona Clayton, a civil rights activist whose foundation was one of the forces behind the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame in Atlanta.

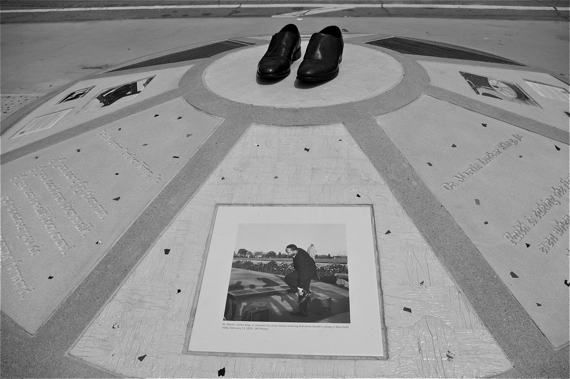

Abeles used bronze casts of King's work boots (above) and shoes worn at marches (below) to anchor her art pieces.

She then used photographs of the shoes of others who played key roles in furthering civil rights to tell a richer story -- one of an ongoing movement whose strength lies in diversity, empathy, creativity, and unwavering commitment to forward motion.

Some of the shoes I spotted at the Rodeo/King site included those of Rosa Parks, James Brown, Sammy Davis, Jr., Sidney Poitier, and Maya Angelou (for background on their efforts and those of others included in the piece, see here).

More interestingly, Abeles took the themes of inspiration, empathy, and “walking” as forward movement a mile down the road to the Jefferson/Rodeo site, where the featured shoes belong to a diverse set of local activists who have made unique contributions to community building.

It was fun to see the names of people I recognized and admired, like pedestrian advocate Daveed Kapoor or Richard Montoya (below), the co-founder of Culture Clash and man behind Chavez Ravine and Water and Power.

The overhaul of the spacious traffic island at the Jefferson/Rodeo site allowed for the shoes to be put on pedestals, as it were, and for the inclusion of a blurb about each of the activists featured. The smaller space at the Rodeo/King site meant that activists' affiliations had to be listed on a plaque on the structure holding King's shoes.

Both are lovely sites and great reminders that there are many ways to serve your community.

My only issue with the installations was their placement.

The Rodeo/Jefferson site is in a location that is not all that easy to access. It is surrounded by fast-moving streets, isn't in particularly close proximity to a neighborhood, and isn't in a pedestrian's natural path. Most of the pedestrians I saw (and they were few) walked along Rodeo to get to the entrance of the Baldwin Hills Scenic Overlook (bottom, left); none crossed to the island.

The site at Rodeo/King is somewhat better situated.

It sits directly across the street from the heavily used Rancho Cienega Recreation Center and is in proximity to a neighborhood. But the intersection itself is highly uncomfortable, meaning that people are often focused on avoiding being run down rather than strolling leisurely through.

The siting of the pieces couldn't be helped, I was told by the Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA).

They were funded by the Percent for Art Ordinance -- a program that sets aside an amount equal to one percent (1%) of the total cost of all construction, improvement or remodeling work for each public works capital improvement project undertaken by the City for art projects.

The program does require that the art be sited within a certain distance of the construction project. This explains, for example, the abundance of amorphous headless animals (or cow splats, to some) around the police headquarters downtown (below).

So, the siting of the Walk a Mile installation was dictated by their proximity to the construction project they owed their existence to -- the Air Treatment Facility at 6000 Jefferson Blvd.

In this case, the DCA had to be a little creative, as there was no place on-site that could both accommodate the project and be accessible to the public. So, they set their sights on the two traffic islands located about a mile apart on Rodeo. This created an opportunity to use the passage between the two sites as a way to both evoke the civil rights marches and use walking as a metaphor for forward movement.

Which would be great, except that, along certain sections of the south side of Rodeo Road, a pedestrian has to move from Rodeo to a parallel side street because the sidewalk disappears. And even where the sidewalk is present, it isn't always a pleasant walk. Rodeo is a fast moving road and some of the large businesses can mean that pedestrians are often dodging folks dashing in and out of big parking lots.

It doesn't mean all is lost. The city could see this as an opportunity to make the most of their investment and improve the walking environment along Rodeo. Given that the westernmost site is also so close to the trailhead for a beautiful scenic overlook, it would actually make sense for the city to do so -- it would encourage health and civic engagement at the same time.

Isn't that how it worked in Field of Dreams?

"Build it and they will put in better sidewalks so all the good people of the land can be healthy"?

Maybe not.

But one could always hope.

The installation at both sites is permanent. More information about the project can be found here. Photos of the opening are available here. More about the Baldwin Hills Scenic Overlook can be found here.