Los Angeles is finally on its way toward realizing the dream of a regional rapid transit system. Five rail lines are simultaneously under construction, and there is renewed momentum to fund another round of transit expansion on the 2016 ballot. Move L.A. recently unveiled a Strawman Proposal for “Measure R2” to accelerate the completion of the remaining Measure R projects and offer a new vision for transit, highway, and complete streets improvements across Los Angeles County.

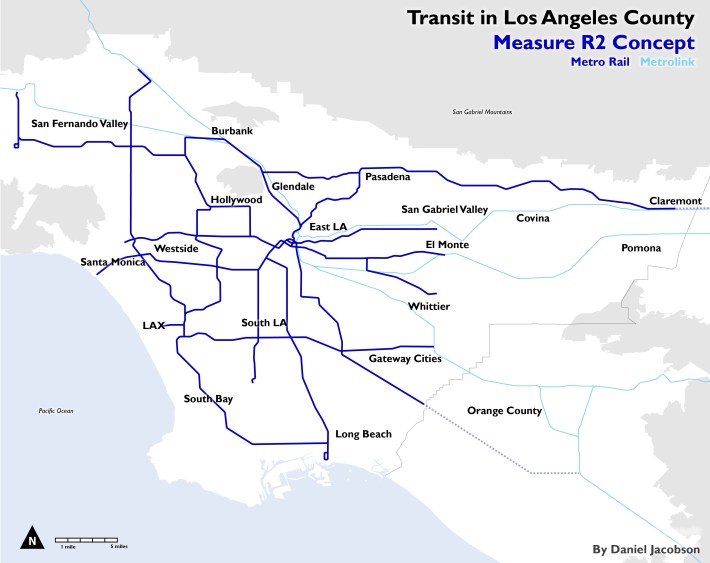

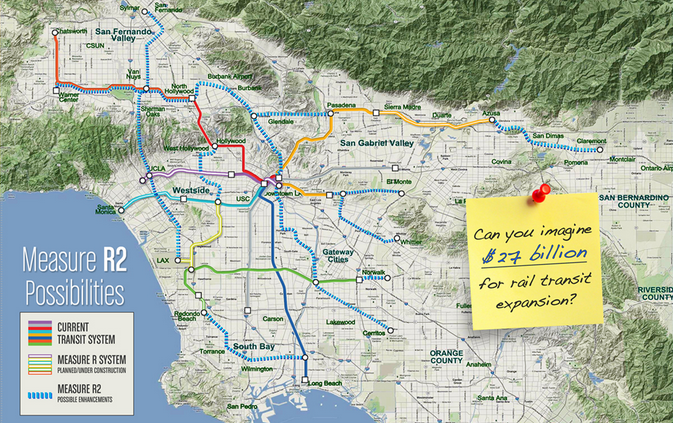

For Angelenos and transit nerds everywhere, there is a lot to get excited about. The centerpiece of Move LA’s vision is a $27 billion expansion of Los Angeles’ rail network (right, and also mapped below). Other features of note include $9 billion toward a “Grand Boulevards” program for complete streets improvements on the region’s automobile-oriented thoroughfares, and $3.6 billion toward active transportation projects. Although Move LA’s vision is just an early draft, a measure along these lines could transform the region—on par with the development of the expansive freeway network half a century ago.

Nevertheless, there's something missing.

Move LA’s Measure R2 proposal does not effectively articulate one of the most critical ingredients to reshaping mobility in Los Angeles County: a spectrum of bus improvements, including bus rapid transit (BRT), to enhance transit service throughout the region.

Los Angeles already has many features of a great transit metropolis, but its greatest challenge is one of geometry: even after another $27 billion rail investment, only a handful of cities, neighborhoods, and corridors will have convenient rail access. For most Angelenos, including many in densely-populated, growing, or transit-dependent areas, buses will continue to serve as the only accessible mode of transit. Rather than rehashing bus vs. rail debates, Los Angeles must embrace upgrades to its bus system (the nation’s second-busiest) in tandem with rail expansion to reach a level of transit abundance that brings frequent, quality service to as many people as possible.

A spectrum of bus improvements are necessary. In many locations, bus stop upgrades to provide adequate shelters, security, and real-time arrival information may be sufficient when combined with frequent service. For other locations, BRT—dedicated lanes and more robust rail-like infrastructure—is necessary to provide quality service and room for growth. Yet, details on bus improvements in Move LA’s Measure R2 proposal are thin: the proportion of funds allocated to transit operations remains constant, and bus enhancements are mentioned only briefly under the Grand Boulevards program.

The lack of a comprehensive regional BRT vision in Move LA’s proposal is indicative of the region’s cautious approach to reallocating street space for buses and other users. While Metro has implemented two (mostly) off-street BRT lines—the Orange and Silver Lines—and an extensive Rapid network, the on-street implementation of BRT has been limited. A handful of “peak” hour bus lanes (7-9am and 4-7pm) have been implemented on Wilshire, Sunset, and Figueroa, and similar treatments have been recommended on nine additional corridors in Metro's Countywide Bus Rapid Transit and Street Design study. However, Metro has currently no plans for more comprehensive bus improvements, such as all-day dedicated bus lanes and rail-like stations.

The city of Los Angeles is effectively leading the charge for bus improvements and more advanced BRT features as it develops concepts for a Transit-Enhanced Network, but the city lacks funds to implement these improvements without its own citywide ballot measure. The city is also is tied to a problematic on-street advertising contract which has limited its bus stop amenities.

A step-by-step approach to BRT implementation makes sense to deliver quick benefits to riders, but it risks setting the bar too low and degrading the benefits of BRT. What Metro presently brands as BRT offers only slight improvements over Rapid service: for example, bus lanes on Wilshire are only active for five hours per day and will be absent in Westwood and Beverly Hills, which opted out. Even after full implementation Metro’s countywide BRT plan, none of the designated corridors would meet the “Basic BRT” standard set by ITDP or come close to being on-par with Metro’s rail facilities.

More than three quarters of Metro’s ridership is on buses, and many more people choose not to ride because the service and amenities are inferior to other alternatives: shelters, safety features, real-time arrival information, and way-finding elements are often lacking, even at the busiest stops. Frequency, speed, and reliability can be all-day issues given the ever-present threat of traffic congestion.

More robust bus improvements are necessary. These improvements not only benefit existing riders, they also makes transit a more useful mobility option for millions of people.

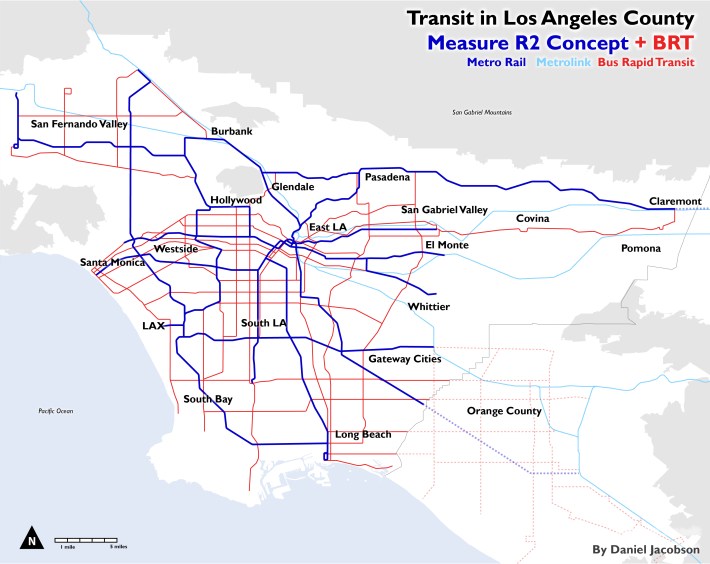

What could a fully developed BRT network look like?

Metro currently operates 400 miles of Rapid service, while other local providers have their own. In total, roughly 500 miles of Rapid services are potential candidates for improvements. 500 miles of true BRT is likely to be cost prohibitive, but it may be conceivable to imagine a mix of improvements such as:

- 100 miles of “comprehensive” BRT (and complete streets enhancements) that could qualify under the ITDP standards (around $4 billion at $40 million/mile - assuming the cost of Metro’s East San Fernando Valley BRT project)

- 200 miles of BRT-lite “Select Bus” service featuring dedicated lanes and targeted bus stop and streetscape improvements (about $2 billion at $10 million/mile - assuming double the cost of Metro’s Wilshire BRT project)

- 200 miles of signalization, bus stop upgrades, and minor street improvements (roughly $500 million at $2.5 million/mile).

All together, a fully-upgraded Rapid/BRT network could cost in the ballpark of $6-7 billion—almost the total budget for the Grand Boulevards program, for which may feature additional non-BRT projects as well. This order-of-magnitude estimate doesn't factor in improvements to the local bus network or associated increases in operating cost to maintain appropriate all-day frequencies for a core transit service.

Despite the cost, a robust BRT investment appears doable within the framework of Move LA’s proposal combined with a mix of local, regional, state, and perhaps federal funds.

For abstract illustrative purposes only, consider the conceptual rail network from Move LA’s Strawman Proposal overlaid with a countywide BRT concept, which assumes upgrades to most existing Rapid lines plus the addition of new BRT services.

This map represents a very rough idea of what an enhanced Rapid/BRT network could look like. The key takeaway is that investing in BRT across Los Angeles County could triple the size of the region’s rapid transit dream for a relatively affordable cost.

These corridor-level investments, when combined with complete streets improvements and transit-oriented zoning reforms, provide the framework for Los Angeles to become a true transit metropolis. Moreover, by addressing the regional geometry challenge, such an investment could achieve greater regional equity: many more people could have access to quality rapid transit service with investments in both rail and buses, compared to just rail. Ideally, rail and bus services would converge to the point that riding the bus would be nearly as pleasant, dignified, and efficient as riding the train, yet buses will serve more places and more trips.

Transit is crucial to the future of Los Angeles: the region is dependent upon expanding mobility options to unlock new opportunities for growth while achieving key environmental, health, and equity goals. Rail expansion will play a key role in reshaping Los Angeles, but a comprehensive investment in transit must extend beyond rail.Los Angeles needs to embrace bus improvements and BRT as core elements of its 21st Century transit vision to foster abundant, high quality transit service for all.

Daniel Jacobson is a transportation consultant working with cities and transit agencies to improve transit, bicycle, and pedestrian mobility in California. He is a transportation planner at URS and a car-free resident of Los Angeles. (The views expressed in this article are his own.)