The city of Los Angeles Department of City Planning is kicking off a series of seven community planning forums starting tomorrow (Saturday, March 15th) and running through April 12th. They're at various locations from Granada Hills to San Pedro. The forums are for public feedback on three citywide planning processes: re:code L.A., Mobility Plan 2035, and Plan for a Healthy Los Angeles. Streetsblog is previewing the citywide initiatives; today it's the city's updated Transportation Plan, called Mobility Plan 2035. See also earlier coverage of the city's new Health Plan.

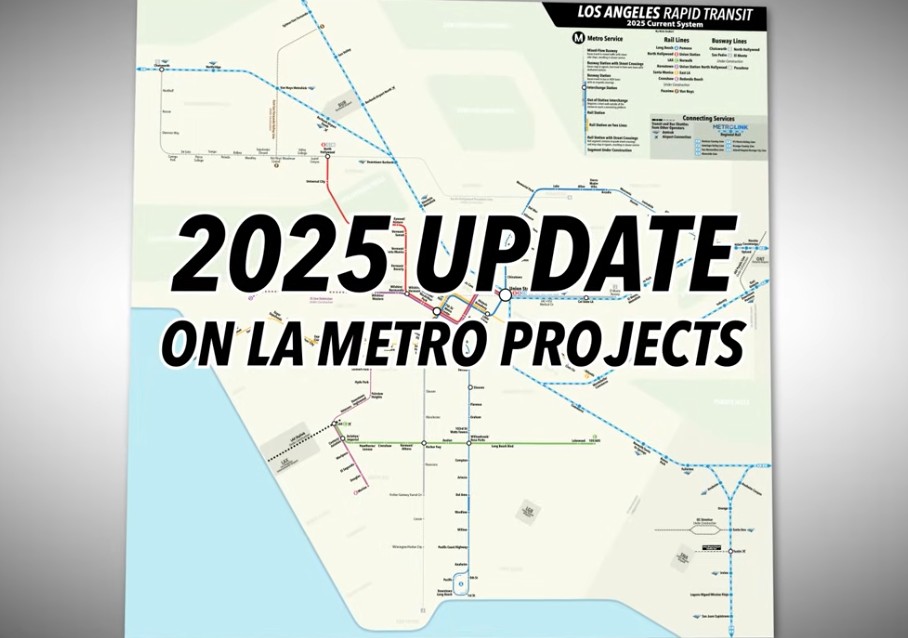

The city of Los Angeles is revising the Transportation Element of its General Plan. What used to be called the Transportation Element has now been renamed the Mobility Element. The title of the plan is Mobility Plan 2035, but it's also known by its eminently hashtagable nickname "LA/2B" which is where you can hang out with the plan online, including via social media.

The Department of City Planning (DCP) released a public review draft of Mobility Plan 2035 (pdf available via LA/2B documents page) on February 13th for a 90-day review period. DCP is requesting public comment on the draft, via the upcoming forums which conclude April 12th, 2014, or via email or in writing. The deadline for comments is May 13th, 2014.

The city last updated the Transportation Element of the General Plan in 1999. The 1999 plan is available on-line (click on General Plan, Elements, Transportation Element.) It has quite a bit of relatively-good livability language, from "parking-pricing strategies," to "transit priority arterial streets" to making "the street system accessible, safe, and convenient for bicycle, pedestrian, and school child travel."

Despite worthwhile policies and objectives, the 1999 Transportation Element didn't make too much of a dent in the Department of Transportation's (LADOT) car-centric practices. Approving good plan language doesn't always translate into on-the-ground change. At least, not in and of itself. And not quickly.

Back to the Mobility Plan at hand. Outreach for the Mobility Plan got underway a in 2012. Through the project website and community meetings, DCP formulated plan objectives and mapped networks.

There's a lot in the plan - from disabled access to parklets to green streets - but there are four main on-the-ground components: districts prioritizing walking and three networks prioritizing transit, bicycling, and vehicles, respectively.

Pedestrian Enhanced Destination Areas or PEDs: The Plan defines PEDs as "locations that have, or have the potential to have, a high number of pedestrians due to their proximity to transit, retail or community services, business districts, schools, parks, or hospitals." These PED areas could feature "pedestrian safety strategies" including "longer crossing times, median refuge islands, automatic pedestrian crossing signals, way-finding, street trees, pedestrian-scaled street lighting, enhanced crosswalks at all legs of the intersection, mid-block crosswalks, bulb-outs, wider sidewalks, specialty paving and seating areas."

Transit Enhanced Network or TEN: The plan specifies the TEN as 237 miles of streets where the city will "prioritiz[e] improvements for transit... relative to other roadway users" through the use of features including "dedicated corridors, transit signal timing, and transit shelters." The TEN is one place in the plan that explicitly references increasing transit's modal share at the expense of driving's modal share.

Bicycle Enhanced Network or BEN: The plan specifies the BEN as a 180-mile street network that provides "low-stress" bicycling "for all type of riders." The BEN adds to, and partially overlaps, the three bike networks in the city's 2010 bike plan: Green, Backbone, and Neighborhood. The plan states that the BEN is meant to "establish a network of Cycle Tracks" (aka protected bike lanes) but the fine print shows it could be "wide bicycle lanes" or "raised bicycle lanes" or "cycle tracks." Additional features that might be seen on larger BEN streets include "bicycle boxes, street lighting, and two-stage turn queue boxes." Smaller BEN streets might see "mini-roundabouts, cross-street stop signs, curb bulb[-]outs, high visibility crosswalks, diagonal diverter[s], bicycle signals and crossing islands at major intersection crossings, bicycle boxes, street lighting, and bicycle-only left turn pocket[s]." The devil may be in the details here. A true protected bike lane with plenty of these features could really transform L.A. streets. A "wide bicycle lane" (perhaps 4 or 5 feet wide?) with "street lighting" would also conform to the letter of the plan.

Vehicle Enhanced Network or VEN: The plan specifies 79 miles of heavily car-trafficked streets (the plan actually describes them as "bombarded by regional traffic") that apparently need even more cars. VEN streets "would prohibit utility work and construction filming activity during weekdays." Additional VEN features would be "limited turning movements, the active enforcement of tow-away zones, time-limited parking areas, ... loading zones and ... reverse flow and peak period lanes."

There's a lot to like in Mobility Plan 2035. The overall sense is that of an emerging multi-modal Los Angeles that embraces walking, bicycling, using transit, and driving.

What's a bit disconcerting in the draft Mobility Plan is the preponderance of weak language. Nearly everything related to bicycles, pedestrians, transit, safety, or livability is couched in non-commital non-legally-binding language like "should," "consider," "contemplate" and/or "guide."

Some examples: (all italics added)

The Plan is... a guiding tool for making sound transportation decisions. It is intended to help the City and other agencies contemplate future actions." (p. 6, overview)

Objectives can be set that will reduce crash and injury rates... (p43, section 1)

In designing roadways, safety considerations for the most vulnerable person should be taken into account first. (p.45, section 1.1)

In order to better facilitate walking and biking within the City, safety improvements and the quality of the environment should be considered to make these active modes of transportation a more viable option. (p. 48, section 1.4)

One can imagine a huddle of LADOT transportation engineers complying with these directives, to the letter, by beginning a meeting by briefly mentioning a crosswalk, then promptly eliminating it in favor of a freeway-width speedway.

Compare the above quotes to this one from the 1999 Transportation Element - the active word here is "shall" as in "shall be widened": (italics added)

Where a designated major highway (Class I or II) or secondary highway crosses another designated highway and then changes in designation to a street of lesser standard width, the street of lesser standard width shall be widened on both sides from the intersection and tapered over the entire length of the standard flare section.

Nobody was out contemplating that widening. The 1999 plan's directions read as a clear and unmistakable mandates.

To be fair, the 1999 plan also uses the words "should" and "consider" - though more often with regards to non-car-throughput aspects of streets: landscaping, medians, scenic byways.

The Mobility Plan is not merely a "guiding tool" for "contemplating" the future of Los Angeles streets. It will be the council-approved policy document that lays down the rules that make streets look the way they do. This plan is the instructions, the recipe, the DNA, for building city streets. The Mobility Plan is an element of the city's General Plan, which is a legally-binding document telling what the city plans to do. Here is the way the General Plan is described on page 29 of the draft Mobility Plan: (italics added)

The General Plan is the fundamental policy document of a city. It defines how a city’s physical and economic resources are to be managed and utilized over time. [...] Changes to the law over the past thirty years have vastly boosted the importance of the General Plan to land use decision making. A General Plan may not be a "wish list" or a vague view of the future but rather must provide a concrete direction.

Perhaps livability can be more than just a consideration by the time the plan reaches its final adopted form. Perhaps the Mobility Plan 2035 can "provide a concrete direction" toward health, safety and equity.

Read the draft Mobility Plan 2035 here. The Mobility Plan also includes a Draft Environmental Impact Report, a Mobility Atlas and a Complete Streets Manual, which Streetsblog will be covering in the near future. Hear more about the city's plans, and give your input, at any of the upcoming meetings. Stay tuned to L.A. Streetsblog for introductions to the city’s Zoning Code update coming soon.