Though I am excited about L.A.'s great bridges, I confess that I am not a big fan of city of Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering's (BOE) "Bridge Improvement Program."

I used to be. In the 1990s the city's bridge program was headed by Clark Robins. After the 1994 Northridge Earthquake, most city bridges received a minimum of necessary seismic treatment to ensure public safety. A few bridges had extensive rehabilitation work, often including restoration of missing historic features. The city won awards and other national recognition for rehabilitating and restoring its wonderful historic bridges.

Then, around 2000, the city moved Robins aside. After some high-profile bridge failures elsewhere, there was plenty of public monies available for bridge work. The city hired consultants to crunch numbers to determine just how large a treasure trove our aging bridges represented. Consultants used approved formulas to declare most of L.A.'s great bridges to be "functionally obsolete."

You might think that bridge obsolescence would be based on, say, seismic testing criteria, right? Though seismic concerns are a factor, most of these bridges were seismically sound. What doomed many of L.A.'s historic bridges were other criteria: the age of the bridge, and the width of the roadway. Pretty much all city bridges more than 50 years old, though seismically stable, were labeled "obsolete."

Bridge consultant sharks could smell blood in the water. There was a lot of money to be made in the "make-work" process of tearing down and rebuilding L.A.'s bridges. And why bother to replace the existing neighborhood-scale bridge, when there was a more money to be made widening it to freeway-scale?

One example of this excessive widening was the North Spring Street Bridge. Today's 43-foot roadway would be widened to a 96-foot roadway. More than double the existing road width! Think of the money to be made! Don't think of the impact of putting another freeway in downtown Los Angeles. (Thanks to historic preservationists threatening a lawsuit and political leadership, the North Spring project was tamed a bit; the 43-foot wide bridge will only be unnecessarily widened to 68-feet. Still a large step in the wrong direction in my opinion, but a less large step.)

With so much public works funding leading to so many ill-considered bridge projects, there were issues. Many of these controversies continue to play out: North Spring Street, Glendale Hyperion, 6th Street, Moorpark Street and others. Additional great historic bridges in the program's cross-hairs include York Blvd (over the Arroyo Seco) and West Blvd (over Venice Blvd.)

I don't claim that all this bridge work is unnecessary, but I find most of these project to be excessive. When you have a flat tire, BOE's bridge builders would probably try to sell you a whole new bicycle... or a car.

Public bridge funding was based on the number of spans to be re-done. Simple San Fernando Valley bridges only have single spans. Many complex L.A. River bridges in central Los Angeles feature multiple spans, hence they are cash cows eligible for multiple times what a single span project could pull down. The Glendale-Hyperion Bridge has at least four independent spans: the main Hyperion Blvd span, northbound and southbound Glendale Blvd spans, and Waverly Drive above.

This brings us to the Riverside-Figueroa Bridge. This L-shaped bridge is located in Northeast Los Angeles; it connects Elysian Valley with Cypress Park.

Riverside-Figueroa has three different spans: the main span over the Los Angeles River, a side-hill viaduct along Riverside Drive, and a span over Avenue 19. Those three spans meant a lot of bridge funding bearing down on an old bridge that has already seen its share of indignities. The initial concrete arch bridge and sidehill bridge were completed in the late 1920s. Avalanches and partial demolition left the lessened bridge that still stands today (hopefully.) Read a detailed bridge history here.

About 10 years ago, the city finalized their plans to tear down the L-shaped historic bridge and replace it with a wider curved bridge. Think freeway ramp. The new bridge would be constructed immediately upstream of the old bridge.

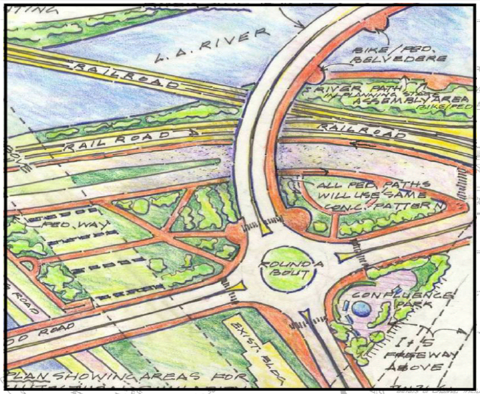

The bridge touches down in Lincoln Heights at the site of the confluence of the L.A. River and the Arroyo Seco, the site of the earliest written account of the Los Angeles area. The area around the confluence had been identified for the river's "Confluence Park." The confluence project was advanced by the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority (MRCA) - essentially a state agency that has been a leader in L.A. River revitalization.

The city bridge program was planning a 4-lane bridge to replace the existing 2-lane bridge. Early traffic studies, commissioned by the MRCA, showed that current and future traffic volumes did not require doubling lane width. MRCA proposed less roadway and more parkland by keeping the bridge to only two lanes and adding a small traffic circle at the intersection of Riverside Drive, San Fernando Road, and North Figueroa Street. City bridge staff persisted with oversized 4-lane designs, but incorporated an outsized 2-lane roundabout at the intersection. The 4-lane bridge includes an extensiton of the L.A. River bike path.

Construction of the new over-sized Riverside-Figueroa bridge began in 2011.

Then a group of community architects and activists came up with a great idea. They proposed preserving the old bridge alongside the new one. The historic bridge would become a park over the L.A. River. Access would only be by foot and by bicycle. There are precedents for similar bridge-parks, including the Santiago Avenue Bridge in Santa Ana and even the High Line in New York City.

They call their proposal LandBRIDGE. See this slideshow at Enrich L.A. for excellent visualizations of how the bridge could be reconfigured. In the short run, preserving the bridge actually saves demolition costs.

The LandBRIDGE story is told well in this earlier Streetsblog article and this subsequent L.A. Times article. Despite a great deal of community and neighborhood council support, BOE representatives have been saying that it's just too late.

I see the LandBRIDGE proposal as a great opportunity. It's not a simple easy change to the project scope. Multi-million-dollar capital projects that spend a decade-plus in development are difficult to re-align... but until the bridge has actually been torn down, it's not too late.

The BOE, under the leadership of architect Deborah Weintraub, has embraced environmentally green buildings. Weintraub has embraced similar projects, but needs more community support to give her cover to do the right thing. Hopefully the city's bridge builders can reconsider their headlong push to destroy great historic bridges, and can retool their designs to make way for a great new space on top of a great old place.

Streetsblog readers can lend their voices in support of the LandBRIDGE proposal by signing this on-line petition.