Listening to reports of the murder of yet another Sikh in the wake of 9/11, my mother looked up at the portrait of my father and sighed, "It's a good thing he's not here to see this."

I had to agree.

Although not Sikh, my father, a Muslim from India, had favored sporting a beard in his final years. What he thought gave him a distinguished air actually made him look more like Saddam Hussein's long-lost cousin. In small-town Wisconsin, where my family lived and where people spouted off openly about "damned towel-heads," this would not have been a good look.

I was in my first year of grad school in international politics at USC that fall and found things weren't all that much better in L.A. Female students complained that other students had ripped their headscarves off and shouted epithets at them as they crossed campus quads. A student club invited an incendiary speaker to come to campus to preach the gospel of nuking the entire Middle East and applauded more loudly with each country he ticked off. Speaking on the topic of hate crimes at a professional conference held in Hollywood, I listened as Muslim members of the audience tearfully confessed to having considered giving their children more "American-sounding" names and to dressing less "ethnically" in order to hide their heritage. I, myself, was even roundly threatened with detention and being put on a watch list mid-flight in front of 200+ other passengers by some overzealous flight attendants who believed themselves to be the first line of defense in the War Against Terror.

In short, one terrible act perpetrated by murderous fanatics had made public space terra hostili for Muslims, those with Islamic names, and Muslim-adjacents (those of Indian or Middle-Eastern descent who were mistaken for Muslims). We weren't just subject to extra scrutiny by the authorities. Neighbors and strangers now felt they had a right to know our business, demand we justify our presence, ask that we denounce the more violence-prone members of our "race," and abuse us if they found our answers wanting.

"Muslims finally know what it is like to be black," I remember joking with friends.

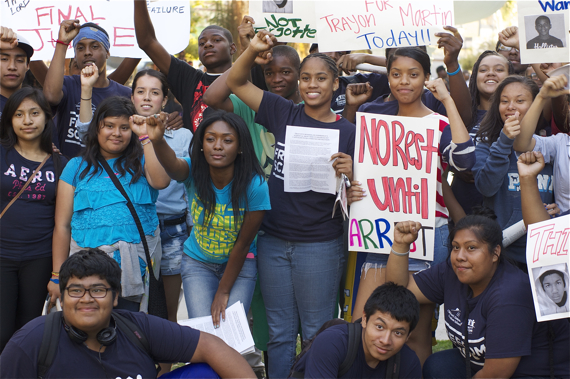

It was with this thought that I headed out to visit the vigils for Trayvon Martin in Leimert Park and Inglewood Monday night. I was not interested in whether or not people felt justice had been served. I knew that answer.

Instead, I wanted people's thoughts regarding a verdict which bolstered the right of civilians to aggressively question the presence, in public space, of "suspicious" people while simultaneously diminishing the right of the objects of suspicion to defend themselves.

It is already hard enough for many to keep their cool and transcend the questioning stares, hostile body language, and other micro-aggressions that Black Kids on Bikes co-founder Jeremy Swift so poetically describes as being "as common as the sun is bright."

The stress of constant scrutiny can even result in post-traumatic stress for some. In the case of the friend of a teen I interviewed, for example, seeing yet one more white woman try to hide her purse upon spotting him coming towards her apparently pushed him over the edge. According to the friend, he snatched the bag out of the woman's hands and then proceeded to berate her for thinking the worst of him until the police arrived to arrest him.

The prospect that some may be emboldened by the ruling in Zimmerman's favor to define their "ground" to be anywhere they see people they do not care for and to take it upon themselves to overtly "stand" and "defend" it is truly terrifying. Especially given that, thanks to some bizarre machinations of logic by the defense, otherwise peaceful people in the immediate vicinity of sidewalks can now be considered to be armed with "deadly concrete" and, therefore, a potential threat against which violence can be used.

Not only has public space been rendered terra hostili for people of color in Florida, in other words, the very infrastructure that facilitates their movement through it can now be used to condemn them.

+ + + +

While speaking with Ben Caldwell of the Kaos Network and artist Rudy Rude about these and other implications of the verdict, I got a text from a friend in Inglewood -- my next destination. Jeremiah Hardwell, a young man who had organized a bike ride to city hall in honor of Martin had been pulled over during the ride and, along with another friend who was also black, arrested.

Maybe that's what all the helicopters are looking at, I thought as I packed up and rode south along Crenshaw.

Nope.

They were hovering over the increasingly rowdy crowd of protesters that had broken away from the peaceful event in the park and were now marching along the boulevard.

While still back at the park, I had heard rumors that someone (perhaps the police) was going to begin strong-arming the crowd around 7:15 p.m in order to provoke fights. Instead, as best I can tell, it was a story generated by members of some of the more radical groups from outside the community -- some of whom were wearing Anonymous masks or bandannas over their faces -- to put people on edge and make them angry enough to march. Right around the time the melee was supposed to start, it was those groups -- not the police -- that gathered their ranks and muscled their way down Crenshaw.

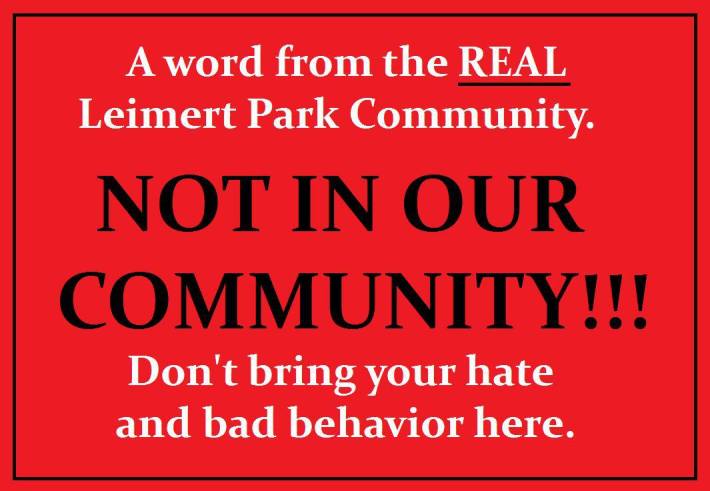

By the time I was headed in that direction, they had already broken the window of a cop car, harassed people waiting at bus stops, stormed a few shops, stolen kids' bikes and scooters, and alienated community members in droves.

Neighbors I spoke with along the street were both curious and taken aback by what they were seeing. Others, nervously watching live feeds of the protests from several of the helicopters hovering overhead, tweeted and facebooked their fears, asking that these protesters get it together and leave the community in peace. Back at Leimert, those organizing the prayer vigil cut the event short, asking that people remain peaceful and pack up and go home.

Although the news outlets would all later acknowledge that the protests had largely been peaceful, there would be very little air time given to what community and youth leaders actually had to say at the vigil in the park. The only images flashing across Angelenos' television screens that night would be those depicting rampant violence and "unrest."

Hooliganism had taken over the story and the bottom-feeders of the world rejoiced: "See?" ran many of the comments on breathless video reports of looting. "We knew black people were violent thugs all along. Now, they've proven it."

+ + + +

When I finally managed to arrive at city hall in Inglewood, I found a quiet gathering comprised of Avan Hardwell, his mother, some friends, and a few members of the Black Kids on Bikes.

Hardwell seemed to be in a little bit of shock.

Just a couple of hours earlier, he had been driving behind his brother, Jeremiah, 27, and a friend, Harold Clark, 24, up Manchester toward city hall. They planned to meet the BKoB group (coming from the opposite direction) there and, together, hold a small candle-lighting ceremony.

They had made sure to publicize their event ahead of time, Hardwell said, so everyone knew that it would be a peaceful affair. Both to be extra sure and because of their passion for the cause, his brother and Clark both sported shirts with "#peace" stamped across their chests.

They were therefore somewhat taken by surprise when they were pulled over by the Inglewood police soon after turning east onto Manchester.

In truth, they probably shouldn't have been so surprised.

In their zeal, they had taken up the left and center lanes (one for each bike) and were moving quite slowly along what is normally a fast-moving three-lane thoroughfare, while Hardwell and his mother followed behind, honking loudly.

Because they hadn't made any signs that explained what they were doing and were holding up two full lanes, drivers and passersby were confused and/or annoyed, and some, according to police, apparently called to complain.

But that all should have been easy to explain to the cops, right?

Not so much.

Apparently, even having your mother along is no guarantee that police will not pull out a taser on you or call several cars for back-up.

That's right.

After nearly knocking Jeremiah off his bike to pull him over, according to Avan, a female officer got out and told him to step to the curb. When Jeremiah asked, "What did I do?" she immediately pulled out her taser.

That's when Avan's heart started racing, he said.

When weapons are drawn, things can only escalate from there, and the person being stopped is the one that will bear the brunt of (and often the blame for) whatever happens next.

Avan immediately yelled out to his brother to move to the curb, which Jeremiah did just as a handful of back-up cars began arriving. Speaking to one of the newly arrived officers, Avan gestured toward his mother and explained that they were participating in a peaceful demonstration, that they had let the Inglewood mayor know about it ahead of time, and that they only wanted to get to city hall, a mile and a half down the road.

Instead of realizing there was a misunderstanding afoot, citing the men for impeding traffic, explaining the rules of the road, and letting everyone move more safely about their business, the police began frisking the men and running their names.

One of the officers asked Avan if the men had warrants.

"Not to my knowledge," he said. These were not the kind of guys that got into trouble.

Suddenly, he saw the cuffs being put on his brother.

A missed court date for a minor traffic violation was now grounds for Jeremiah's arrest. A minor ticket from 2010 for riding a bus without a fare that Clark thought he had taken care of years ago had apparently not been cleared. So, he was also cuffed. He was released later that night but Jeremiah was held through the next day.

"I never thought I'd see one of my sons arrested," Hardwell's mother told me with a heavy heart as they were packing Jeremiah's bike into their car to go home. "But at least he was doing something that he believed in."

+ + + +

High-flying news helicopters droned ominous greetings as I headed back into L.A. and towards Leimert Park.

It was now after 10 p.m. and the police had closed off several blocks along Crenshaw Blvd. to keep people from driving into the intersection at Vernon. The hundred or so protesters that had been causing trouble hours earlier were still aimlessly milling around in the street and in the park area, making a lot of noise, and occasionally picking fights with each other.

Mainly, they were just making the LAPD very nervous.

To their credit, the hundreds of officers on hand seemed genuinely interested in acting with as much restraint as possible (which I heard community members thanking them for as they left the scene).

But it didn't mean the officers weren't worried.

Those gathered at the southwest corner of Vernon and Leimert could be heard asking, "What are they doing now?" "What's going on?" "What are they filming?" "Did you see that?" while watching pockets of people coalescing to chant or surrounding a car. In the dark, it was hard to tell what was happening and the earlier spates of violence had everyone preparing for the worst.

Community members gathering along the east side of Leimert Blvd. at Vernon were also curious about what the outcome would be, but made sure the police understood they were keeping their distance.

"We just got out of football practice. We're only here because we stopped to get some food!" two sturdy teens passing through said, waving their bags and soft drinks at officers and glancing uneasily at the crowd.

Nobody wanted to be associated with a melee, if one broke out. Instead, they took to speculating amongst themselves about who the more violent protesters were and why they had taken the approach that they did.

I lamented to an older white police officer that it was a shame that outside groups had come to an otherwise peaceful community event and upset things with their own disruptive agenda.

"It gives the community a bad name," I had said.

He looked at me like I was crazy.

"I was here in 1992! It's the same people!"

It was my turn to look at him like he was crazy.

Most of the people I was looking at hadn't even been born in 1992 and probably knew very little about the history of the riots. Many weren't even from the area. This wasn't even civic unrest, as some have labeled it -- this was opportunism, pure and simple.

And it wasn't helping anyone's cause -- least of all the image of young people of color.

It was painful to watch, so I left.

+ + + +

In the days following the verdict in the Zimmerman case, people of all colors and creeds have struggled with how exactly to respond.

With peaceful demonstrations getting "hijacked" by unlawful people, some leaders have begun to call for a halt to the protests and a renewed dedication to the documentation of wrongs and to lobbying for legislative change.

Social media has been all a-twitter with people changing out their profile pictures for ones of themselves in hoodies of solidarity. Essence Magazine launched a #HeIsNotASuspect campaign, encouraging parents to post photos of themselves with their sons to challenge negative images of black males in the media. There's also the well-meaning, if somewhat puzzling, "We are not Trayvon Martin" page, where posters declare that, while they may not have experienced profiling, they are determined to fight racism wherever it rears its ugly head.

While the outpouring of virtual solidarity is a lovely thing to see, I'm not sure it really means much unless it manifests in transformative action of some sort on the ground.

I don't mean demonstrations.

I mean small, personal efforts by individuals from all walks of life to expand their social boundaries.

A comment made by a very well-educated and successful white acquaintance of mine who was explaining why she did not ride Metro might explain what I am getting at.

"Sahra," she said slowly and carefully, with her hand on her chest, "I'm not used to being a minority and I'm uncomfortable when I am put in that position."

I took that in for a minute and nodded slowly, ruminating on the realization that she was genuinely unaware of the privilege inherent in that statement and all that it implied.

Namely, that a lack of familiarity with people unlike herself led her to be wary of them when they outnumbered her -- as if they might want something from her, or would ostracize her for being white, or god knows what she thought they might do when they had the chance, really. Whatever it was, it was enough to keep her from venturing too far from her socio-economic comfort zone.

Unfortunate a sentiment as it was, I understood where it could have come from.

And, for what it's worth, I hardly think she's alone in that way of thinking.

"Aren't you afraid you're going to get shot?" is still the number one question I am asked when people hear I work in South L.A.

"Why on earth would you want to hang out there?" is another.

There's my personal favorite, "I wouldn't be caught dead in Watts. Ha ha, no pun intended."

And evidence that segregation goes both ways, "USC, huh miss? I bet you see a lot of white people there." (from a high school student in East L.A. wondering what it would be like to be in a non-Latino environment).

In short, Los Angeles is still a tremendously segregated city.

That segregation means people are unfamiliar with each other. That unfamiliarity breeds reliance on stereotypes. Those stereotypes -- usually negative -- fuel fear. Even the most well-meaning people who abhor racism and care deeply about social justice can still be fearful of others, simply because they are unfamiliar with a community.

So, while people may feel compelled to make a tumblr post or demonstrate to show they are in solidarity with a community that is hurting right now, it may be that the best thing they can do is to participate in a community activity completely separate from anything having to do with Trayvon Martin.

In South L.A., that might mean attending the upcoming artwalk in Westmont or in Leimert Park, taking a ride with the Black Kids on Bikes, East Side Riders or Los Ryderz, volunteering to read to youth at Community Coalition's Freedom School summer program, helping plant a garden in someone's front yard with L.A. Greengrounds or volunteering at Community Services Unlimited's urban farm, participating in a Summer Night Lights Program at one of several South L.A. parks, or visiting the iconic Watts Towers and spending an afternoon in beautiful Ted Watkins park.

It may not feel like the sexiest way to get your protest on, but it might be the most effective.

Reaching out across boundaries to reclaim public spaces as sites where people of all races can build community together will help undermine the fears that allowed for Trayvon Martin's death to happen in the first place.