*This is a sister-story to our recent piece on how the new security measures around USC resulted in the increase in profiling of lower-income youth of color around the campus. Read that story here.

"We do not believe at this point that there is any indication that this [incident] was race-based,” Capt. II Paul Snell of the LAPD Southwest Division told 1000 attendees at a forum last Tuesday night to address the mistreatment of black students by the LAPD when shutting down their party on May 4th.

People’s eyes rolled back so far in their heads, it looked like some of them might get stuck that way.

Too many in attendance had either been on the scene, had friends who had been there, or had seen the many images, videos, and detailed accounts of students describing how 79 officers (some in riot gear) had used bias, aggression, bullying, excessive force, and even racial slurs to disperse a party of minority students celebrating their last day of classes.

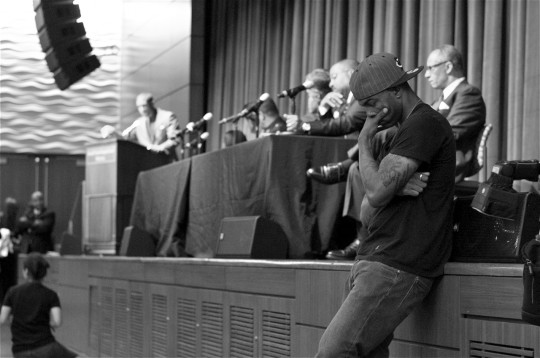

I reached out to squeeze the heavily tattooed arm of Tommie Bayliss, a student at the cinema school who I had watched grow increasingly agitated while awaiting his turn to address the panel of officers and USC officials.

“Are you OK?”

His head snapped up in surprise.

After a long pause, he nodded, “Yeah.”

I didn’t buy it.

Just minutes earlier, he had been demanding accountability and shouting questions to the panel out of turn. His friend and a co-organizer of the event, Jay Sneed, had quickly rushed over to settle him down while Rikiesha Pierce, another event organizer and author of a Neon Tommy article about biased policing at a party in mid-April, took to the microphone.

“They can't hear you when you’re screaming,” she admonished Bayliss. “You gotta stand. You gotta be decent. You have to come with understanding and intellect."

Bayliss has understanding and intellect in spades, and he recognized the importance of decorum. But he also saw the forum was quickly coming to an end, which meant he wasn’t going to have a chance to say his peace publicly.

Too passionate about the issues on the table and about what he wasn’t hearing from panelists to let that happen, he finally moved to stand directly in front of the stage while Sneed was still delivering the evening’s concluding remarks. He wanted to be the first to speak with Deputy Chief Bob Green when the forum officially ended.

He had good reason to be agitated.

The 35-year-old undergrad from Compton had managed to transcend poverty, substance abuse in his family, the loss of a parent, homelessness, incarceration, discrimination, and the harshness of some of Compton’s tougher streets to get where he was today.

He was thirteen when the riots broke out in 1992, and already well-versed in just how oppressive law enforcement could be toward young black men. He remembered the days when officers could ram down the doors of suspected crack houses with impunity and LAPD Chief Daryl Gates put South L.A. on notice by warning he had no problem with his officers shooting casual drug users.

The acquittal of the officers involved in the beating of Rodney King, Bayliss said, was the moment when African Americans knew for sure that they were on their own. Here they had proof of a horrific beating on camera, and it still wasn’t enough to convince people to hold law enforcement accountable for abuses against blacks.

While the stakes at the party were not quite as high, he acknowledged, it was frustrating to feel like little had changed.

How could it be that there were so many images, videos, and statements from witnesses about encounters that smacked of outright racism and yet the LAPD was still making the claim that they had seen no evidence of bias?

How could it be that all that work he had put in to moving his life forward meant nothing to the officer who shoved a baton into his chest several times as he tried following orders to go home?

Yes, he had gotten mad that night, he told me as we chatted later, but he had seen his friend and host of the party, Nate Howard, thrown up against a wall by a cop who told him, “I can do whatever I want.”

Given that kind of attitude among the rank and file, Bayliss wanted to know, how could he be assured that promises commanding officers were making to implement changes were going to be kept? And, what form would those changes take?

Would it just be that parties wouldn’t be so heavily policed any more?

Or would Bayliss finally be able to dress in something other than USC gear when out in the neighborhood and be seen as a whole person by law enforcement rather than a potential "thug"?

His friend Sneed summed up those questions best while delivering the closing remarks. As a graduating senior who had been raised in a part of town known as The Jungles, Sneed wondered if leaving the shelter of a powerful institution like USC would affect how far his voice would carry.

He would continue to fight to be heard, he said, even “once I’m gone [from USC and] I no longer have the leverage to be able to get a crowd into the RTCC Ballroom, and I’m left with nothing but my skin color and people’s perceptions of me.”

“I been through too much…” he said. “Something has to change.”

# # # # # #

When he began his remarks, Sneed had told the audience, "If we weren't USC students, we probably wouldn't be having this forum.”

He was not wrong. The story of how USC's new security measures had resulted in aggressive profiling of lower-income youth of color around campus had largely been received with sadness a few weeks ago, but it hadn’t sparked any serious anger or demands for accountability.

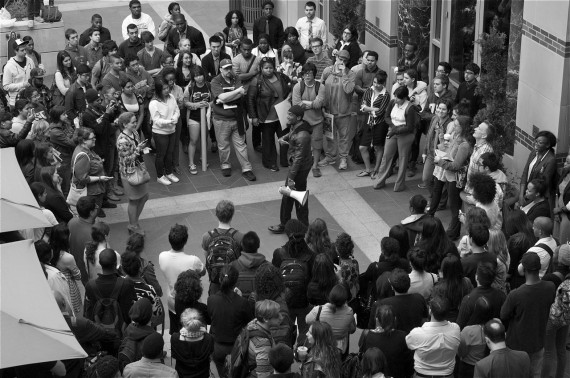

In contrast, the forum to hear students’ testimony drew multiple press outlets and hundreds more people than could safely fit inside the campus ballroom.

The forum had originally been organized with the Department of Public Safety (DPS), the LAPD, and University administration officials prior to the May 4th incident to address more generalized concerns of racial bias in policing of minority students. It took on a much greater significance, however, after video, images, and complaints went viral on social media.

Suddenly, everyone from anti-establishment protesters from the ‘60s, to veterans of the Watts Riots, to black students on campuses around Southern California were eager to hear what changes would be put in place to ensure something like this never happened again.

The difference in the responses to the two sets of profiling claims is noteworthy, I think, because of what it implies about legacy media’s perception of who counts as a credible witness and whose stories we, as a society, consider to be of value.

The incident on the night of May 4th, for example, created an almost a perfect storm of conditions, ensuring the story would eventually hit the headlines.

For one, the minority students affected weren’t marginalized neighborhood kids that the rest of the student body saw itself as separate from. Instead, these were students widely recognized as unimpeachable scholars and powerful leaders by the USC community as a whole.

Unlike the youth I interviewed about profiling, they were also not afraid to step up and call out injustice. When the students couldn’t get the press to respond to their calls, they began posting videos, photos, and stories from that night all over social media. The story blew up almost immediately, finally attracting requests for interviews from the very same press outlets that had first turned them away.

Perhaps most importantly, everything went down in front of white witnesses.

In fact, it didn’t just “happen” in front of these witnesses. The largely white students had completely different encounters with the same law enforcement officers who were said to be pushing their minority friends and classmates around.

Officers worried openly about the safety of white students, some students reported. They warned them to stay inside the Pink House -- located across the street -- where an equally loud party was underway. Other students described their horror at seeing peaceful black party-goers who were attempting to help disperse the crowd treated disrespectfully, handcuffed, and called the n-word.

Even more disturbingly, some of the white students claim that police entered the Pink House later that evening without permission or a warrant, entered the bedrooms of sleeping students (some of whom, women included, were not fully clothed), and tried to get them to make statements to the effect that police had been justified in handling things the way that they did. Which the students refused to do.

Instead, these students’ accounts of the evening have figured prominently in several media stories (see here, here, here, here, and here), lending a legitimacy to the black students’ claims that might not have otherwise been granted.

# # # # # #

As he was leaving the forum at the end of the night, Chief Thomas reminded me that he was still waiting for me to get the neighborhood youth together to speak with him about their concerns regarding DPS’ mistreatment of young men of color.

“I’ll go anywhere,” he said, ticking off locations where kids might be comfortable in talking to him, like parks or back alleys.

I had to laugh. No kid I know wants to meet an officer in a back alley.

And the chaos of the forum had just made clear that wasn't the way forward, either.

The disconnect between the kind of force the commanding officers say they are striving to build and the behavior of the rank-and-file officers on the ground and in communities is too great. And it isn’t clear what policies and accountability structures the top brass plan to put in place to bridge that gap.

Any efforts to effect change must ensure not only that officers who profile are held accountable, but that the culture that permits and even rewards biased policing also finally changes for good. Just altering a policy at the top and hoping the effects trickle down is not enough.

Take, for instance, the internal shifts within the LAPD that have been made to focus on questions of constitutional policing when reviewing complaints. The installation of 300 cameras in South L.A. cars in 2010 and the assignment of a full-time officer to review footage of recorded stops are a key part of the effort to help the department catch, punish, and reduce blatant incidences of biased policing.

All of which is good, I told Deputy Chief Green, except that some of the rank and file are so wedded to their biases that they have adapted their practices to get around the recording equipment.

As the officers were aware that the equipment goes on when they get out of their cars, some were now intentionally avoiding activation of it by harassing youth about their parole status from inside their vehicles, according to many of those interviewed.

Not only does that make it challenging for anyone to verify claims of profiling, supervisors are left in the dark as to the real nature of the relationship the officers have with the community they are supposed to serve.

When I asked Capt. Snell about the challenge of making deeper changes to the culture within the rank-and-file, he agreed that there was a problem and that change was slow.

Much of the intransigence stemmed from the fact that the new recruits were young and inexperienced, he said. He and some of the other officers on the panel that night had 30 or so years with the force under their belts. They had lived through so much together and grown with communities, he said, while newer officers lacked that experience and understanding of how to work in partnership with communities.

Which may be true to some degree.

It is not, however, a viable excuse. First and foremost because there’s no justification for racism or biased policing, no matter how new you are. But also because it’s law enforcement’s job to work with communities.

The more experienced officers know that the better they are able to work in collaboration with communities, the easier it will make their job and the safer those communities will be. Even Deputy Chief Green made sure to underscore his belief in the importance of community-based policing as the most effective way forward when addressing the forum attendees.

Why that more public health model/preventative/collaborative approach to policing doesn’t appear to be the one that is taught, shown by example, or expected of officers as the norm isn’t clear. Is it a lack of resources? A shortage of support structures for senior officers? The wrong kinds of measures of success (i.e. numbers of juvenile arrests vs. numbers of juveniles where alternatives to arrest were found)?

Whatever the reason, it is clear that something needs to change. And that any change needs to be department-wide and in collaboration with the community – not just something done to fix what happened at USC.

Sneed made that message personal by telling the forum crowd, “If you guys are gonna just focus on USC students… man, I’m a black brother first and I grew up in L.A., second. What are you going to do for [kids like me]?”

“How are we going to protect ourselves and protect other people from these situations?”

He called on the officers and the attendees to work together to create an inclusive, holistic community where everyone was safe and treated with respect.

“That’s what it should be. That’s what it is going to be.”