"Nobody uses it," Liz told me. "There's dookies in there!"

She was referring to the 53rd St. pedestrian bridge connecting the two halves of the Pueblo del Rio housing development split by the four sets of Blue Line and Pacific Rail train tracks.

Dookies, piss, and people waiting to relieve you of your possessions -- the pedestrian bridge unfortunately appears to have it all.

The fact that it sits largely unused -- although perhaps unsurprising, given the fact that it is both fully enclosed and very long (favoring ramps over stairs) -- is disheartening to say the least. The bridge was constructed in 2001 with the intention of making the community safer.

The project had originally been proposed in 1996, but didn't move forward until middle-schooler Gilberto Reynaga was killed in 1999 by a passing train. Reynaga and his friend were returning home from playing basketball on a mid-summer's afternoon when they came across a stopped freight train blocking the intersection at 55th St. and Long Beach Ave. Apparently thinking that the flashing lights were for the stopped train only, they clambered over it and made their way toward the Blue Line tracks (which run parallel with the Union Pacific tracks for much of their trajectory through South L.A.). They didn't see the southbound Metro train until they were already on the tracks.

With neighbors screaming at them to get out of the way, they panicked and ran for it. Reynaga didn't make it, and was subsequently dragged under the train.

The whole community mourned, Liz, whose family runs a mini-market at that intersection, told me. "The funeral was huge -- so many people came. It was the biggest funeral ever."

"The Deadliest Rail Line in the Country" or "The Greatest Concentration of Traffic-Sign-Disobeying People with Death Wishes"?

We've all heard the Blue Line called the "deadliest rail line in the country."

Streetsblog has even done some of that name calling and railed against Metro for suggesting that some of the fault lies with us because "people have a responsibility to obey both the active and passive warning devices."

Although Metro acknowledges that the deaths of 70+ pedestrians and 28 motorists over the past two decades isn't something to brag about, it isn't a title they are willing to accept without some qualification.

A significant percentage of the deaths along the Blue Line are confirmed suicides -- 30 since 1990. Four of the six fatalities last year, in fact, were confirmed as such.

The two pedestrian deaths this year also seem to point to questions of personal responsibility. The gentleman killed at Vernon in January ignored the flashing lights, bells, and lowered pedestrian crossing gate and, according to Metro staff, opened the pedestrian swing gates and, with his hoodie up over his head, walked right in front of the train. Sylvester Henderson, killed at the Century and Grandee intersection, ignored the lowered crossing gates and bells, crossed the Union Pacific tracks, and rode his bike into a Metro train that was already crossing through the intersection.

"People think they can beat the train," says Vijay Khawani, Executive Officer for Corporate Safety.

And to a degree, that seems to be true. Looking over some of the incidents compiled here (only current through 2008), it is not uncommon to see witness descriptions noting it appeared the decedent or injured party was in a hurry, sometimes tripping and falling in front of the train as they were running to catch it. Implausible as that sounds, a teen I mentored told me that was exactly what had happened to her sister-in-law. Heavily pregnant and worried about being late, she made a dash for the station at San Pedro as the train was pulling in. She was unable to get up when she tripped and fell in front of the train, killing herself and her unborn child.

Even a Metro bus got its back end clipped last year after trying to get through an intersection before the train arrived.

Speaking about safety concerns with myself and Marc Littman (Deputy Executive Officer, Public Relations) in his office the other day, an exasperated Khawani said there wasn't much he could do if people refused to obey the warnings and gates. He's even been told by the Public Utilities Commission to be careful about over-saturating crossings with warnings and signs because it can overwhelm and confuse people, ultimately being counterproductive. And, while the Blue Line does not have all the safety features that you see along the Gold and Expo Lines, Khawani assured me it does meet and even exceed minimum safety standards.

Still, suicides aside, pedestrian incidents along the other lines that run at grade are few and the vehicular collisions are usually the fault of an impatient or even distracted driver, like the USC student who, after leaving the showroom lot in his brand new car, was showing off the GPS system to his friends when he drove in front of the Expo Line test train, completely totaling the $67,000 vehicle.

So why does the Blue Line have such a poor record, comparatively?

What if it isn't the Blue Line?

A number of explanations have been floated for the reason the Blue Line is comparatively deadly, ranging from suggestions that Metro is racist to the idea that the South L.A. community must be to blame. Perhaps the most unusual idea I heard was one offered by a member of Metro's staff who suggested that the Mexican community that lived along the Gold Line in East L.A. were used to co-existing with rail lines because of their experiences in Mexico, and therefore had more respect for the line.

I am not quite sure how long one has to live near a rail line to get used to it, or what that says about the many people of Mexican origin in South L.A., some of whom have walked in front of trains, but this person was quite convinced that heritage held the key.

Moreover, the community structure and composition also made it easier to do outreach and educate the community, he said. It wasn't so easy to reach adults in South L.A.

Setting aside any concerns about the implications of that line of thinking, given that Metro's Spanish translation of the "Do you see lights?" safety campaign signs their trains sport is incorrect, reading, "Do you look at lights?" (Mira luces?), I wouldn't necessarily consider Metro Mexican cultural specialists.

After spending a day riding my bike alongside the Blue Line and hanging out at crossings, it seemed to me that, at least at present, the current problem is not racism, non-Mexicans who are not used to trains, the Blue Line itself, or (for the most part) current Metro safety measures.

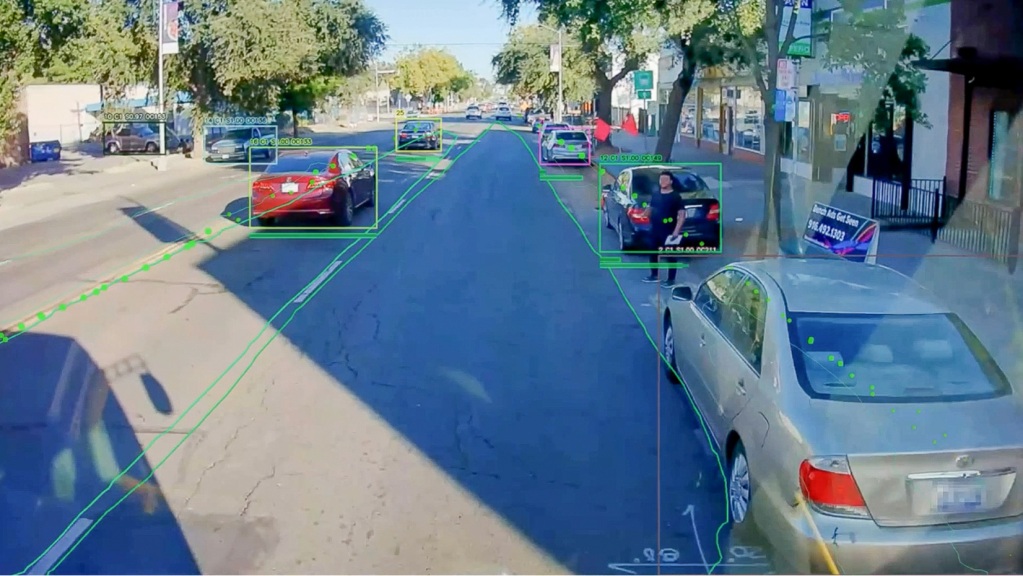

The problem, from my casual observation, is that only one side of an intersection benefits from Metro's safety infrastructure throughout much of South L.A.

One or two sets of Union Pacific rail tracks run alongside the Blue Line tracks for much of its trajectory. Because Union Pacific manages thousands and thousands of miles of tracks, they have been reluctant to supply their South L.A. crossings with anything more than the most basic of safety measures.

What this means is that, at present, pedestrian traffic is only partially adequately halted through the use of infrastructure like ped barrier arms (see photo below). People entering the intersection from the Union Pacific side encounter no such barriers and are consistently more likely to move across the tracks, even while the lights are flashing and trains are approaching.

I wondered if perhaps I was crazy for thinking this might be the problem, but a look at the pedestrian fatalities between 2002 and 2012 indicates that, of the 18 non-suicides in South L.A., 13 happened at crossings between Vernon and Imperial, where a pedestrian must cross four sets of tracks. Only 5 happened in between the 7th St. Metro Center and San Pedro station (before the Metro tracks meet up with the UP tracks), and at least two were cases of the victim running for the train and falling on the tracks.

The majority of the incidents between Compton and Long Beach also seemed to follow this pattern (although there was on only one set of UP tracks in some spots instead of two), with the notable exception of a sight-impaired man falling onto the tracks at Del Amo and a few people being hit at major intersections where other factors may have come into play.

It certainly doesn't explain everything -- as noted above, the January incident at Vernon was due to someone ignoring the pedestrian barriers on the Metro side -- and I don't know how this plays out with regard to injuries and other incidents. There were 842 minor collisions with the train between July 1990 and June 2009 (1/5 of which involved pedestrians) and, according to a four-part safety series by Steve Hymon "complete data on who was to blame in all of these accidents [is] unavailable." But the dynamics of the UP crossings may help explain why the other rail lines do not experience such incidents.

The wide openness of the crossings and lack of barriers on the UP side seem to give people a false sense of security -- they are sure they will see a train coming. Because the freight trains only run once a day (instead of a dozen or more a day, as in the past) and move so slowly, often inching forward, backing up, stopping, and inching forward again, they may lull people into thinking that the Metro trains are less dangerous than they are. Or throw off their calculations of which side a train is coming from, how fast it is moving, or how quickly they themselves can get across the tracks. Ask any jaywalking pedestrian in the area and they will reassure you they are more than capable of getting across the tracks in time.

Add in the many distractions safety ambassadors report people are occupied with that keep their heads pointed down at their phones instead of looking around them, and it is no wonder that these crossings have been problematic.

Metro to the rescue?

As Khawani explained, much has been done to try to make the line safer in recent years (see a list of improvements current through 2010 here).

Of note, Metro has conducted presentations at schools and left door hangers with safety information at people's homes along the train route. Safety ambassadors at a few spots along the Blue Line deliver those messages in person while the LAPD has not been shy about ticketing those making unsafe crossings. Citations have also been delivered thanks to photo enforcement. Train operators have even been taught to drive defensively and use methods to get the attention of drivers that appear not to see them.

Pedestrian barriers (where a gate arm comes down across the sidewalk) or swing gates (peds must open to pass through) have been installed at a number of major intersections, as have flashing "train" signs, improved crosswalks, "Look Both Ways" signs, and quad gates (where all four lanes are blocked) at a few intersections in Compton that had previously seen several collisions. Trains sound their horns loudly as they approach intersections and stations, and their now brighter "cyclops" lights flash to draw attention as the operator sounds the horn. Even the trains themselves are wrapped in banners reading "Heads Up! Watch for Trains!"

And now, Metro plans to go even further, Khawani said.

After finally getting the long-awaited go-ahead from Union Pacific, Metro set aside $7.5 million to install additional gates and signage along the UP side of the crossings.

He pulled out a thick packet of marked-up draft drawings of Blue Line crossings to show me how Metro was working to determine which safety measures could go where.

Some streets and intersections would need to be shut down in order to be reconfigured with the kinds of features seen on the newer rail lines -- something they don't see as being able to do.

That doesn't mean that improvements won't be made. But, it isn't as simple as putting up gates everywhere, Khawani explained.

Some of the pedestrian walkways that lead toward the tracks just don't have room for particular improvements. A wheelchair-bound person, for example, would have to roll back into the street to be able to open a pedestrian swing gate at some spots along Long Beach Ave. In such cases, improvements like flashing lights embedded in the sidewalk may have to suffice.

They hope to have the projects ready to be submitted to the bidding process by July so that improvements could get started during the upcoming fiscal year.

Metro is also launching a partnership with the Didi Hirsch Suicide Prevention Center and will be posting 600 signs with information about where to call at the ends of platforms (where people are most likely to jump) and at different high speed crossings and known spots (i.e. there have been three suicides near Spring St.) along the train route in the hopes of reaching those in need.

"We can't afford to put a bubble around the Blue Line," said Khawani.

But, being able to move forward on the measures they have long had on the table are a good start. Getting the green light from Union Pacific to put safety infrastructure on their side of the crossings is a huge step forward.

Hopefully, people will heed them once they are operational. If not, perhaps Metro could make another call to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to help them get the word out about safety.

What's that you say? You didn't know the Ninja Turtles have saved the day for Metro before? Behold: