Just before the elections, the L.A. Times definitively declared that "South L.A.'s zeal for politics has faded."

That declaration seemed unfair for two reasons.

One, the article was not actually asking residents of South L.A. about politics, in general. It was asking whether or not black people were still enthralled with Obama and believed that his presidency would bring change to their communities.

Two, the author is measuring South L.A.'s participation in politics and political activism by a vote cast once every four years. And they probably won't return to ask South L.A. any questions about their political opinions until the next election rolls around.

It is true that there is some disillusionment with the Obama Administration's ability to push back against Republican obstinacy and lift up poorer communities of color. Blacks were the first to lose their jobs when the recession hit and the last to be hired as the economy began to recover. Black unemployment is about double that of white unemployment. And, given that the foreclosure crisis hit communities of color harder, those who lost their homes no longer have the equity necessary to start their own businesses, should they want to entrepreneur their way out of their situation.

But, this larger disillusionment with the system is not new. The community has long felt overlooked by politicians and often complain that, despite raising their voices, their concerns go disrespected or unrecognized altogether. Or, past disappointments mean they may not trust that the issues that concern them will be addressed in ways that benefit their communities. Or, they would like to be involved, but do not know how to access the necessary information about the issues or relate the issues to their own circumstances. As a result, many may not see the more formally recognized institutions of democracy as being the right channels through which to exercise their voice.

This doesn't mean they are not invested in the well-being of their communities and not promoting democracy in their own way. They just don't wait for political institutions to be their salvation. Instead, the South L.A. I know is a very vibrant place teeming with organizations that work hard to address the needs of residents in ways that the political establishment does not.

Take Community Coalition, for example, an organization founded in the wake of the crack epidemic that devastated the area in the 1980s. Dissatisfied with the institutionalization of a punitive approach to their communities, they have looked to the engagement and organizing of neighbors as the best way to build community-centered solutions and tackle the root causes fueling crime, addiction, and violence in the area.

Political organizing is part of that -- at an event in April commemorating the 1992 uprisings, community speakers emphasized the importance of being part of the formal political process. And last night, it was well after dark when CoCo youth volunteers were returning from the final push of their weeks-long educational and get-out-the-vote efforts to join in the election results-viewing party.

But community engagement means much more to them than just registering people to vote. It means filling in the gaps left by the public sector and providing residents with the resources they need to educate themselves on the issues. And, it also means listening to the community and addressing the wider range of what are often very pressing needs.

Eva, a former youth organizer who had come back to help out with phone-banking in favor of Prop 30, summed up her philosophy on politics by saying that she saw herself as having two options: to help lessen the suffering of others or to do nothing.

And she just didn't see "doing nothing" as a viable option.

Part of her contribution was taking the time to explain propositions or issues to local residents. People would thank her, she said, for calling or knocking on their door to help them see how the issues related to them and why their voice mattered.

That kind of one-on-one attention and respect was new for many of the residents she spoke with, she said.

But much of what she had done with CoCo as a youth leader involved working with other youth to make tangible change in the community. Ensuring that foster youth could participate in activities or campaigns and have a voice, she said, was important to making kids who usually are the most isolated and most at-risk feel like they were part of a community and had a contribution to make. Feeling her own voice mattered to her, too, even though she had come from a stable two-parent home.

"I didn't feel listened to," she said. But, at CoCo, she felt "used" for the first time.

"That sounds really bad," she said, "but it isn't like that..."

Instead, Eva felt that, for the first time, she was heard and could be useful to her peers and her community; like what she did would make a positive impact. The more she participated, the more she felt like she was part of a powerful family, something a number of people I spoke with that night expressed.

CoCo is definitely a multi-generational affair, George, the former staff-member who introduced me to Eva told me. Many of those that came up in the organization as youth went on to become CoCo staff or to work as activists in other community organizations in the area. Something which seems to be one of CoCo's most powerful political impacts -- building a culture of community engagement is the most sustainable way to move a community forward.

Eva was certainly a product of that. The training she had received as a youth leader had not only propelled her on to school, but also inspired her to come back to her community and do in-home counseling work with foster youth.

When asked if there was anything about her work that surprised her, she immediately offered an unexpected answer: "I didn't know that my community was considered 'high risk' and 'high need,'" she said.

Hearing people at work talk about how "nervous" they were to go to such a "dangerous" area took her aback. It was weird to know that people judged her community that way.

"They were talking about the school down the street..." and places where she grew up, she shook her head.

"I just thought we were a regular community...with regular people."

They weren't any different or more dangerous than anyone else, she said. They just wanted to be listened to.

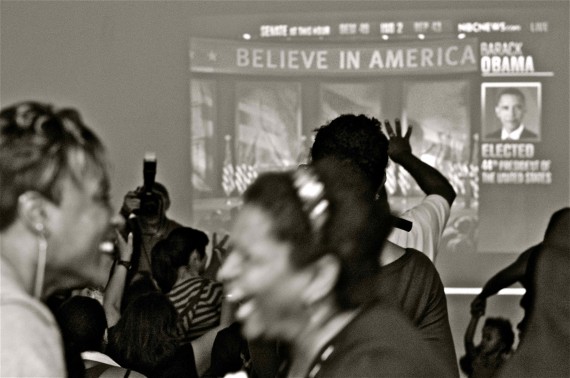

A lot of those dedicated "regular people" had gathered at CoCo last night to cheer, dance, and hug each other in response to the victory of Barack Obama. Others in surrounding neighborhoods shot fireworks off when the announcement came that he had reached 270 electoral votes.

But the election was just a momentary distraction from the work at hand.

Alberto Retana, Executive Vice President of CoCo, handed me his card and invited me to sit in on a meeting Thursday evening. It will be an exploratory meeting intended to begin the process of forming a youth coalition. They want to reach out to youth in their twenties, Retana said, because they want to know more about what their needs are. They've got a good handle on the needs of teens and the 35-and-up generations because of the active participation of those groups in their activities, he said. The twenty-somethings are their next target.

The "zeal" the Times was looking for is definitely there, in others words. It just comes in a more comprehensive, longer-term, and non-election-specific form.