Over the past few months, we've checked in on the efforts of five communities in Los Angeles County to create more livable, walkable, bikeable and healthier communities through better transportation planning through the Los Angeles PLACE Grants. However, Los Angeles County is home to 11 million residents, and less than 750,000 live in PLACE communities.

But that doesn't mean that the LA County Public Health Department (LACDPH) doesn't have a plan for the rest of the county. Partnering with the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation, LACDPH awarded a RENEW Grant to create a "Model Street Manual" to help the rest of the county, and anyone else who was interested, begin to think of their streets in a different way.

"It's time we started designing our streets for people and quality neighborhoods instead of just cars," explains super-planner Ryan Snyder, the lead consultant for the plan. "We hope the street manual will change the way cities here and across the US design their streets. The manual should be real a game changer."

The manual starts with an explanation of the difference between traffic control devices, the application of which is controlled by the state, and traffic calming which isn't. The state's Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices biases streets towards moving traffic makes installing traffic control devices a difficult undertaking. Making a difference between traffic calming and traffic control is an important legal distinction, because if a municipality deviates from state rules, it could be found at fault in traffic crashes.

For example, stop signs, traffic signals, and flashing beacons are expected to meet minimum thresholds before application. These thresholds include such criteria as number of vehicles, number of pedestrians or other uses, distance to other devices, crash history, and more.

Traffic calming, such as speed humps and bump outs, don't fall under the same restrictions. Thus, municipalities are encouraged to adopt a strategy of slowing traffic to increase street safety as one of many practices to make streets safer for all users.

The manual also lists the benefits of adopting a true "complete streets" ideal when completing road projects. The benefits are many, and this list is probably familiar to many Streetsblog readers, but seeing the list together creates a striking picture.

- The goals of designing living streets are to

- Serve the land uses that are adjacent to the street; mobility is a means, not an end

- Encourage people to travel by walking, bicycling, and transit, and to drive less

- Provide transportation options for people of all ages, physical abilities, and income levels

- Enhance the safety and security of streets, from both a traffic and personal perspective

- Improve peoples’ health

- Create livable neighborhoods

- Reduce the total amount of paved area

- Reduce streetwater runoff into watersheds

- Maximize infiltration and reuse of stormwater

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollution

- Reduce energy consumption

- Promote the economic well-being of both businesses and residents

- Increase civic space and encourage human interaction

While the manual doesn't give a list of the potential negative impacts of promoting living streets, we've prepared a list for comparison purposes.

- People driving cars will find it more difficult to drive dangerously

So how do we get from a traditional street design to one that emphasizes the first list of benefits over automobile speed?

It would take forever to go through all of the individual treatments available to municipalities, but the basics aren't going to surprise any regular Streetsblog reader.

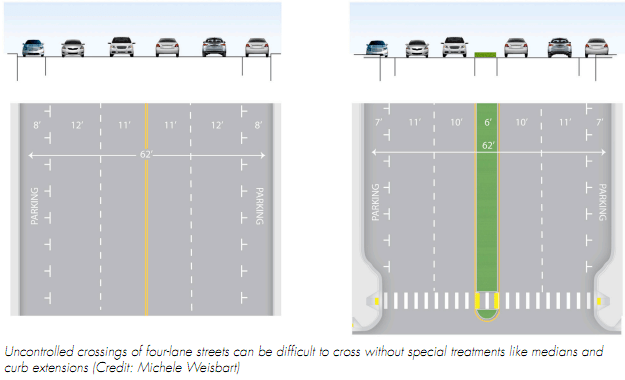

One of the main keys, of perhaps greater importance than bike lanes or large sidewalks, is the quality of the road intersections. A disproportionately large amount of crashes occur at intersections and the design of the intersection can also lead to dangerous intersections throughout the street. For example, many community activists point to a lack of stop signs and stop lights as the main reason a community is unsafe, but in many intersections, there are better options. For example, traffic circles (aka roundabouts) is a superior treatment at many residential and other intersections.

Of course, providing a safe way for people to cross at an intersection is also paramount to creating safe streets, crosswalks, bike and pedestrian countdown timers, wayfaring signage and bike boxes (painted areas that give bikes priority at intersections) are all different treatments that provide a safer way for people to mix with cars in addition to a traditional crosswalk and pedestrian light.

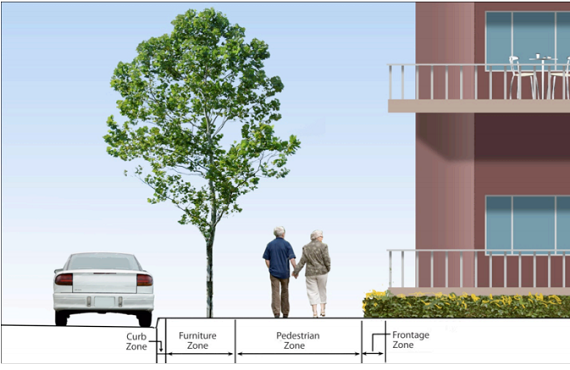

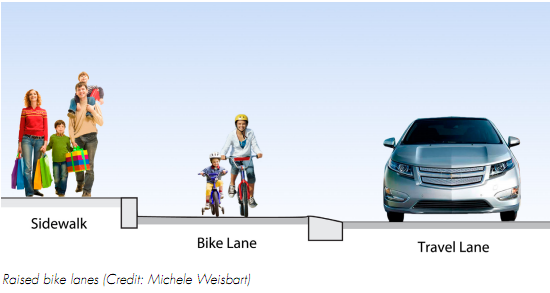

Of course, the manual addresses Pedestrian Crossings, Bikeway Design, and Transit Accommodations as important components of creating a complete street. A series of treatments are proposed that takes space currently dedicated to moving cars to moving people. Bus bulb outs make it easier to get on the bus and reduces traffic speed in areas where pedestrians and cars mix. Separated bike lanes gives bicycles their own space on the street. Sometimes, the most impressive designs are the most basic. The manual also gives sidewalk design guidelines for areas with different uses and densities, covering everything from office parks, to main street, to a suburban residential area.

My favorite chapter is on "Streetscape Ecosystem." A truly Livable Street is all about multiple uses in the public space. I love the parts about creating furniture, waste cans, public art and shopping areas, the text about storm water runoff and rain water management is equally important. After all, a Livable Street is a Green Street.

Last but not least is the density and land uses that surround the street. Just as its important to build a street to match the existing development, its important to plan development to match a street.

Snyder describes the manual as a "game changer," but its also a challenge. No longer do communities have the excuse of not understanding smart growth principles or the claim that its "impossible" to change a street's DNA. The manual and its team have created a public framework for anyone to use. The challenge to urban planners and transportation engineers everywhere is whether or not they have the courage to.

(Full Disclaimer: Two of the contributors to the manual, Deborah Murphy and James Rojas, are members of the LA Streetsblog Editorial Board.)