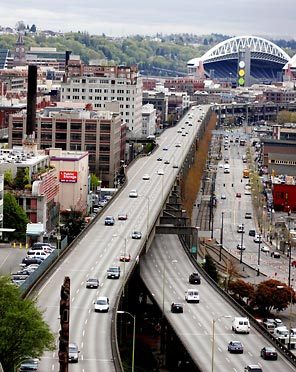

One of the most gripping local transportation debates in the country has been unfolding in Seattle, where the replacement of a highway along the waterfront known as the Alaskan Way Viaduct presents an opportunity to completely rethink a core piece of the city’s transportation system. So far, public officials have cast their lot with a plan to replace this elevated highway with an underground highway buried within a deep-bore tunnel.

Dan Bertolet at PubliCola argues that the tunnel plan is based on the erroneous assumption that maintaining car capacity transcends all other transportation objectives. Excess urban highway infrastructure, even if you deck it over with parks and public space, is antithetical to promoting more sustainable transportation, Bertolet writes:

A common argument made in support of a deep-bore tunnel to replace Seattle’s Alaskan Way viaduct is that by putting all those cars underground, we’ll end up with a better pedestrian and cycling environment on the city’s downtown streets, the waterfront street in particular. That position may sound logical, but not unless you disregard several key realities of cars and cities.

First of all, focusing on how the tunnel would impact downtown streets ignores the impact it will have elsewhere. As I discussed in a previous post, car infrastructure inherently sabotages travel by walking, biking, and transit. The reinforcement of car dependence caused by the tunnel will dwarf any progress on alternative modes that might be made in isolated pockets of downtown Seattle.

Furthermore, there is a major flaw in the underlying premise that with a surface-only viaduct replacement scheme, utilizing the downtown street grid to make up for lost car capacity along the waterfront would force us to take space away from bikers and pedestrians. Because that premise only holds if you accept that car capacity is sacred.

New York City’s removal of car travel lanes along Broadway is an unqualified success story. They didn’t have anywhere else to put all those displaced cars, but that didn’t stop them from doing it anyway. And this rejection of the “car capacity is sacred” mindset is the path that Seattle policy makers will also have to get on if we ever hope to make a meaningful transition from our current state of unsustainable car-dependence…

Whatever configuration of street ends up getting built along the Seattle waterfront, it will eventually fill up with cars, even if we spend billions on a bypass tunnel.

In the case of the viaduct, to me that choice is a no-brainer: a low-speed, two-way, four lane boulevard along the waterfront. Yes, this will constrain car capacity. But here’s the reality: Reining in capacity is the only way we will ever make significant progress towards reducing driving, a goal that is not only aligned with basic principles of sustainable urbanism, but also happens to be an adopted goal of the State of Washington.

Elsewhere on the Network, Cyclicious highlights an upcoming bicycle safety discussion taking place in Orange County, California, where an average of one cyclist per month is killed on the roadways; Missouri Bicycle and Pedestrian Federation assails a proposal in St. Charles County to ban bikes on several roads; and Tucson Velo asks what amenities compel people commute by bike by examining a local map comparing Census data on travel modes.