Corporate disinformation has played a key role in creating America's deadly transportation culture — and it will keep happening until advocates learn to spot the most common forms of spin and organize against the policies they helped create, a new book argues.

In the newly released Dark PR: How Corporate Disinformation Undermines Our Health and the Environment, author Grant Ennis breaks down the specifics of how automakers, fossil fuel companies and roadway engineers, have lied about the dangers of car dependency — and manipulated the public into believing them.

In the newly released Dark PR: How Corporate Disinformation Undermines Our Health and the Environment, author Grant Ennis breaks down the specifics of how automakers, fossil fuel companies and roadway engineers, have lied about the dangers of car dependency — and manipulated the public into believing them.

A lot of that corporate spin, of course, will be all too familiar to sustainable transportation advocates, who have long criticized car companies for calling crashes "accidents" and exposed journalists who echo corporate talking points about why pedestrians shouldn't have "jaywalked" on roads with no crosswalks.

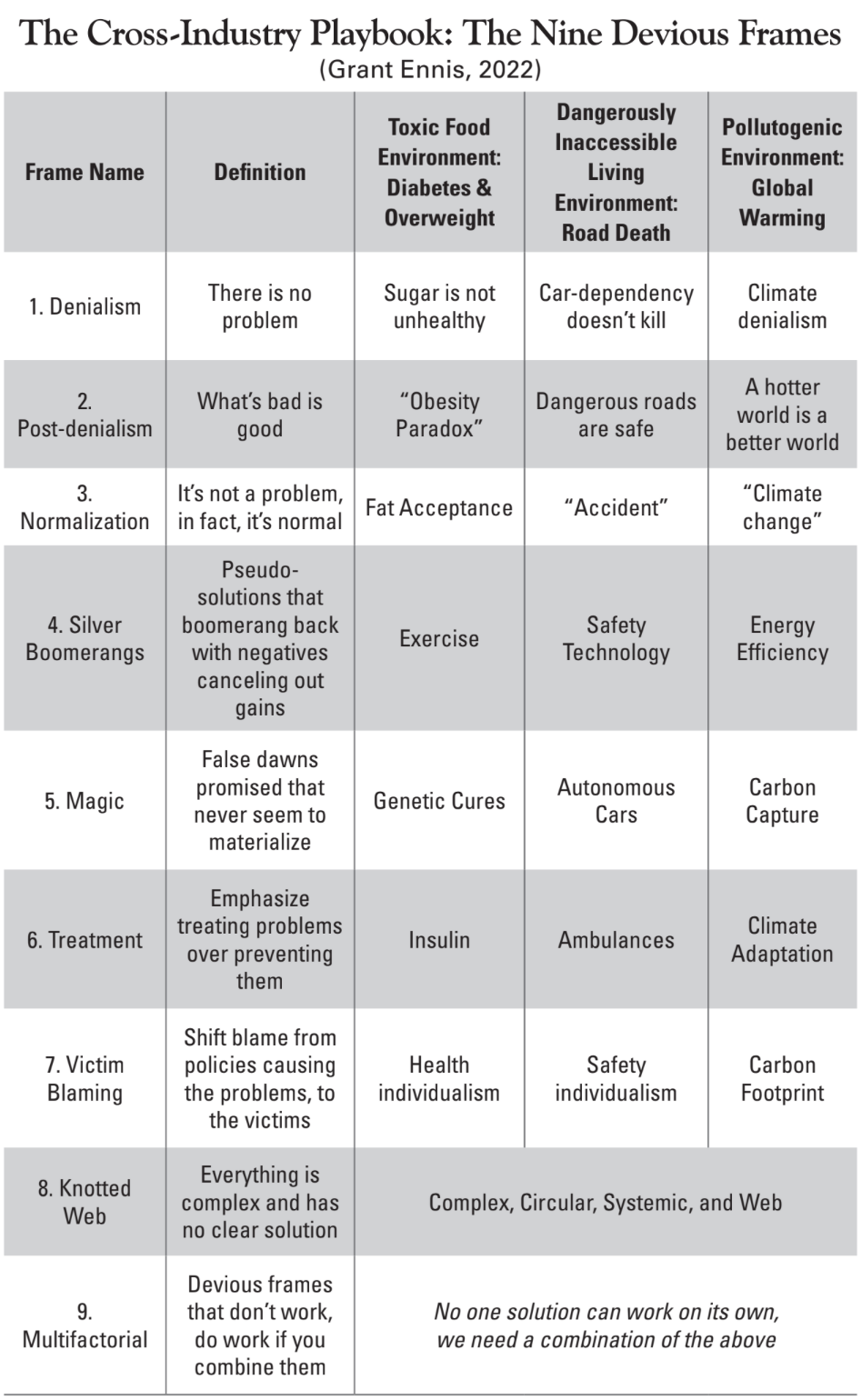

Victim-blaming and the normalization of deadly violence, though, are just two of what Ennis calls the "nine deadly frames" that corporations use to manipulate people around the world into accepting the death and wide-spread damage their products cause — and some of them are so subtle that even the most avowed advocates might not realize they're at work.

"[When I started writing this book,] people said 'Grant, you're promoting the nanny state,'" Ennis said in an interview with Streetsblog. "But really, we already have a nanny state, and the nanny is killing us. ... The fossil fuel industry, the road industry, the automobile industry, they all use the same narratives to distract us from [dangerous] structures that are all around us."

Here are the three major categories of disinformation to watch out for.

1. Lies

The most obvious form of disinformation, of course, is the good-old-fashioned, bold-faced denial. Ennis points to decades of fossil fuel companies' efforts to argue that climate change is isn't real, or the auto industry's insistence that deadly speeds are perfectly safe for capable drivers who make the investment in cars with the latest safety features.

Equally dangerous, though is what Ennis calls post-denialism, wherein companies acknowledge the deadly downsides of their product, but insist that they're actually a good thing if you just look at it all through the right lens. It's a big part of how road-widening projects that decades of research show will increase deadly crashes for pedestrians who struggle to cross are sunnily sold as roadway "improvements" because they'll make streets smoother, faster, and better ... for motorists.

"You have corporate sponsored efforts to say that sprawl is good for us, that low-density land use patterns are actually nicer, that suburbia is a great place to live, a safer [place to live]," Ennis adds. "But a lot of people die from car crashes in the suburbs."

2. Panaceas

The only thing better than a highway "improvement" or a better car feature, of course, is a do-it-all wonder product that will solve all the problems that car culture has caused — if we can just hold out a little longer for the technology to be perfected.

In the era of autonomous car hype — which, Ennis points out, began pretty much around the same time as the non-autonomous car was invented — manufacturers are increasingly framing the automobile of tomorrow as a kind of magic that will soon end crash deaths forever without asking us to drive even a little bit less.

And when the magic doesn't materialize, corporations simply throw out what Ennis calls silver boomerangs, or false "silver bullets" that they know won't solve the problems their products create, but might convince us they will just long enough to make another sale — until the side effects of that magical solution whip back around and smack us in the face.

One Norwegian study, for instance, found that the owners of electric cars actually drove more than owners of gas powered ones, which experts say may have decreased the emissions benefits of their fuel-efficient rides by replacing what might have otherwise been walking, biking or transit trips; partial vehicle automation, meanwhile, create some safety benefits when driver assistance systems are working, but they also create automation complacency, so drivers are dangerously distracted when imperfect systems fail.

And if none of those dazzling cures work, Ennis says, corporations can always default to the myth that good treatment can solve our problems after the damage has been done... so maybe we don't need to work so hard to prevent the damage in the first place.

"[It's why] McDonald's and all these food companies are donating money to hospitals, [why] you see General Motors buying ambulances and giving them out for free, why you have people like Rex Tillerson saying that we can 'just adapt' to global warming," he adds. "It's not that any one of these things wouldn't be great; I mean, if we could get carbon capture storage to work, that'd be fantastic, and we should definitely have lots of ambulances. ... But, of course, we're never really going to solve these global, population-level problems [with treatments after the fact]."

3. False complexity

Perhaps the hardest corporate myth to bust, though, is the one that's the closest to the truth: that the problems of car culture are thorny and complicated, and so we must be patient as we chip away at them slowly ... and not be too surprised if they never fully fall away.

Ennis stresses that ending car culture as we know it will be a difficult war fought on many fronts, and that Vision Zero advocates are right to attack all the dangerous systems woven into our transportation landscape. When an auto industry lobbyist talks about how solving the traffic violence crisis is like unraveling a knotted web, though, that's often little more than a tactic to divert attention from the fact that their company is one of the spiders that helped spin it — and what it could do right now to cut the threads.

"The term 'systems thinking' and 'systemic approaches' have been a bit hijacked," added Ennis. "We really need to be talking much more about structures."

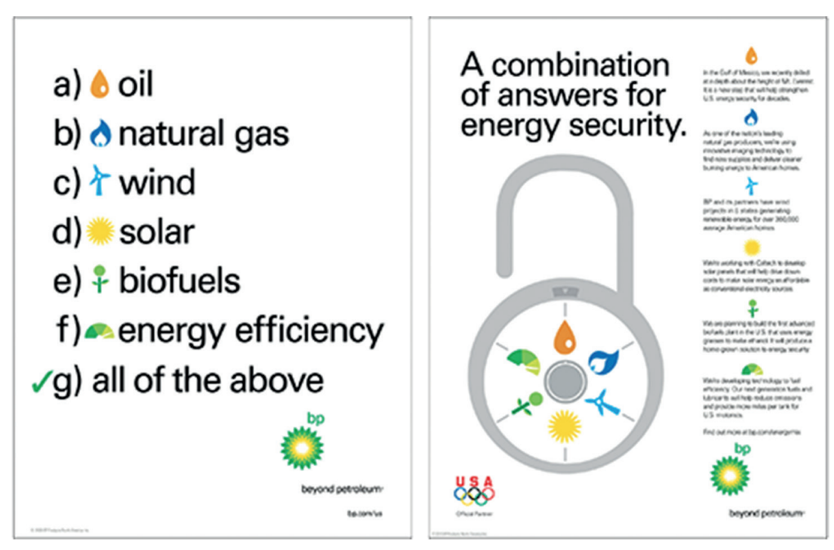

Even when the auto industrial complex does try to remediate the damage it causes, though, Ennis says they often do so in a way that puts a suspicious amount of emphasis on the multifactorial nature of the crisis they're helping to solve — and then uses that framing as a smokescreen to continue their harmful business practices. Think oil companies who stress the importance of solar and wind power to complement fossil fuels (but never seem to stop drilling), and car companies who sponsor safety contests and even devote whole departments to nominal micromobility projects (but still seem to keep selling bigger SUVs every year).

"It's the idea that we can't solve anything until we do everything," said Ennis.

Ennis acknowledges that the nine devious frames work so well because they each contain at least a kernel of truth, and that can make it hard to decide which messages are sincere. By learning to spot corporate spin, though — and never forgetting to consider the source — he believes advocates can organize to make a difference.

"We need to be concerned about the way that [these messages are] weaponized by corporations to affect legislative change," he adds. "The solution really is to organize, and to fight for the nanny state that's killing us to be changed."

Look out for an extended version of our our conversation with Grant Ennis on an upcoming episode of The Brake, a Streetsblog Podcast.